Ancient quarries in Israel reveal where Homo erectus hunted and butchered elephants

Researchers suggest ancient quarry sites in Israel were favored because they were close to elephant migration routes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient humans quarried flint to make weapons for hunting and butchering elephants up to 2 million years ago in what's now the Upper Galilee region of Israel, a new study finds.

The research answers long-standing questions about why there were so many ancient quarries in the region, and found that they were located near water sources likely used by migrating elephant herds.

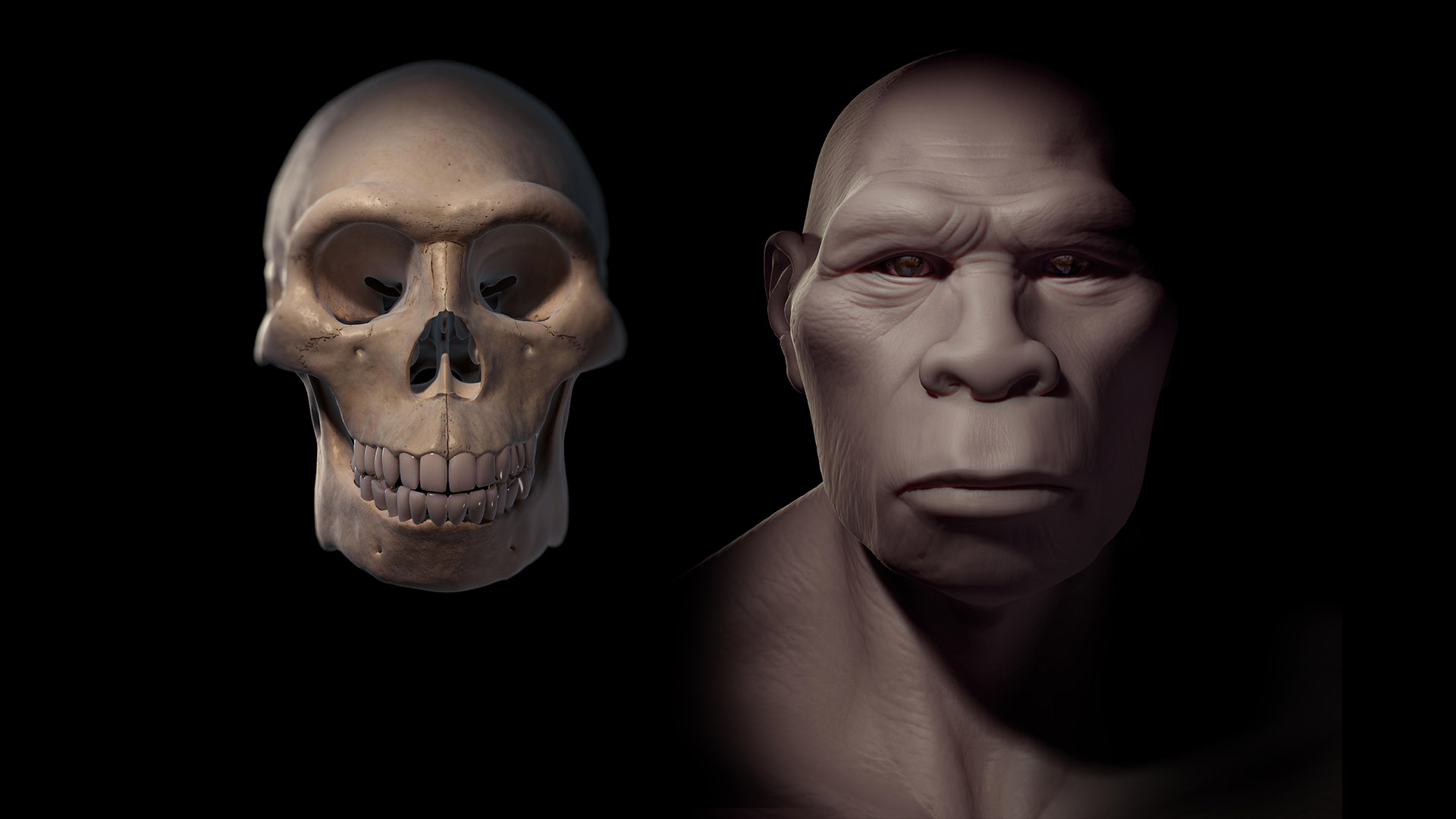

The study authors propose that Homo erectus — an early ancestor of modern humans that lived from about 1.89 million to 110,000 years ago — quarried flint at the sites to make tools for hunting and butchering elephants until about 500,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic period, or Old Stone Age.

Article continues below"An elephant consumes 400 liters [105 gallons] of water a day, on average, and that's why it has fixed movement paths," study co-author Meir Finkel, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University, said in a statement. "These are animals that rely on a daily supply of water, and therefore on water sources — the banks of lakes, rivers and streams."

The authors looked at the ancient migration routes of elephants — suggested by earlier studies that considered the landscape and fossilized bones — and found that they corresponded closely to the ancient quarry sites in the Upper Galilee region, according to the study published Feb. 21 in the journal Archaeologies.

The quarries are within walking distance of the major Paleolithic sites at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov and Ma'ayan Baruch in the Hula Valley, between the Sea of Galilee and Israel's borders with Syria and Lebanon.

Related: Our mixed-up human family: 8 human relatives that went extinct (and 1 that didn't)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sacred stone

The study authors noted that the prehistoric elephant hunters seemed to have considered the flint from particular outcrops especially suited for hunting their prey. Ancient humans even left offerings at these rock outcrops, while leaving neighboring outcrops untouched.

"Hunter-gatherers attribute great importance to the source of the stone — the quarry itself — imbuing it with potency and sanctity, and hence also spiritual worship," co-author Ran Barkai, a professor of archaeology at Tel Aviv University, said in the statement.

Barkai and his colleagues have studied the flint quarrying and toolmaking sites in the Upper Galilee region for nearly 20 years. Earlier studies had shown that elephants were the primary food source in the region for Homo erectus by comparing the location of the ancient human sites with the ancient elephant migration routes.

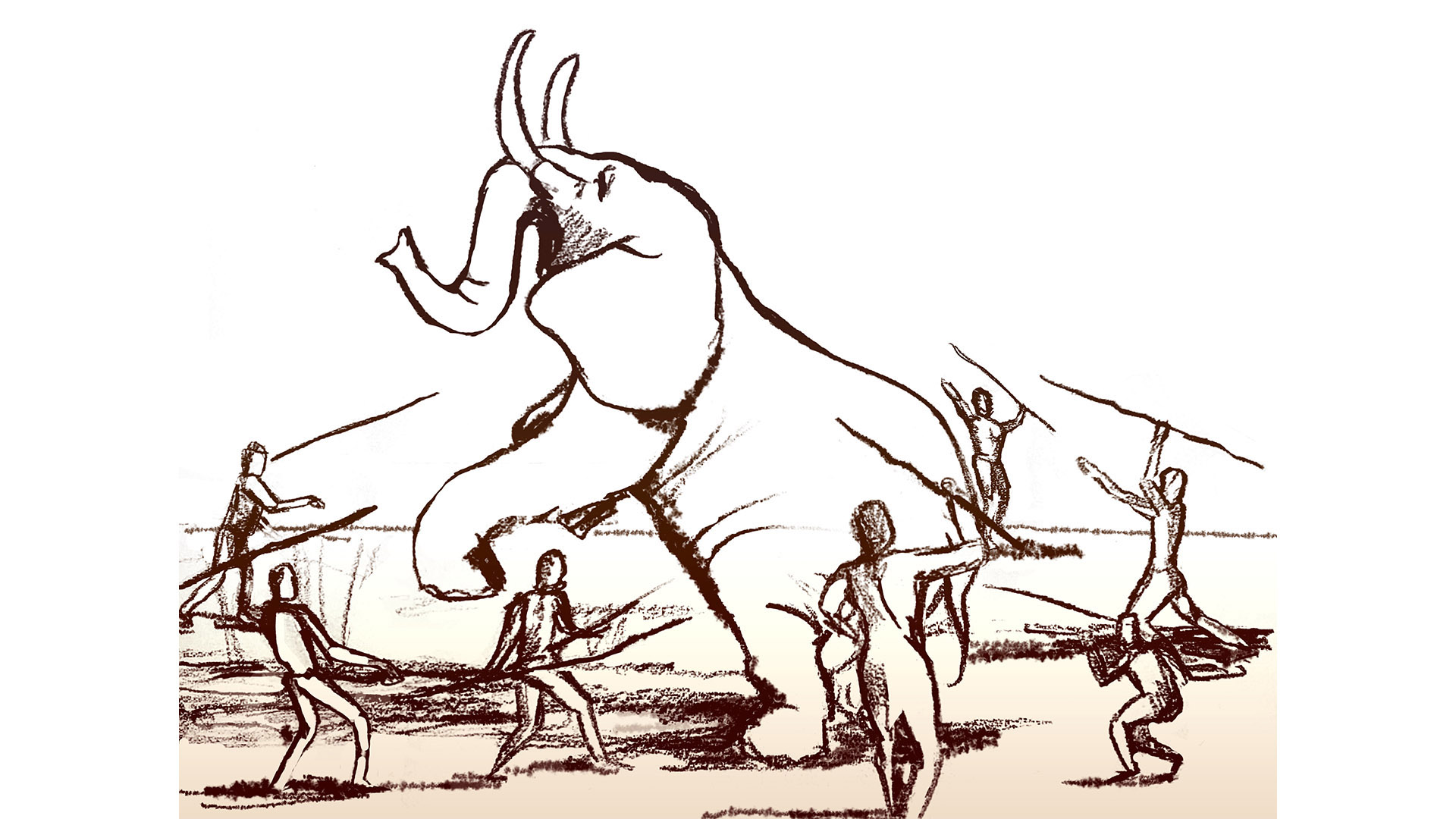

"In many instances, we discover elephant hunting and processing [butchering] sites at 'necessary crossings' where a stream or river passes through a steep mountain pass, or when a path along a lakeshore is limited to the space between the shore and a mountain range," Finkel said.

Because it was hard to preserve an elephant carcass, especially with nearby predatory animals, ancient humans wouldn't have had long to butcher a dead pachyderm. "Therefore, it was imperative to prepare suitable cutting tools in large quantities in advance and nearby," Finkel added.

To support their theory, the researchers applied their findings to those of early Paleolithic sites in Asia, Europe and Africa where elephants and mammoths were hunted and to later sites where other animals — such as hippos, camels and horses — were the prey.

"It appears that the Paleolithic 'holy trinity' [water, prey animals and suitable stone] holds true universally: Wherever there was water, there were elephants, and wherever there were elephants, humans had to find suitable rock outcrops to quarry stone and make tools," Barkai said.

"It was tradition: For hundreds of thousands of years, the elephants wandered along the same route, while humans produced stone tools nearby," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus