Ancient language found on 2,100-year-old bronze hand may be related to Basque

Researchers think the inscription is written in a Vasconic language spoken in northeastern Spain before the arrival of the Romans.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

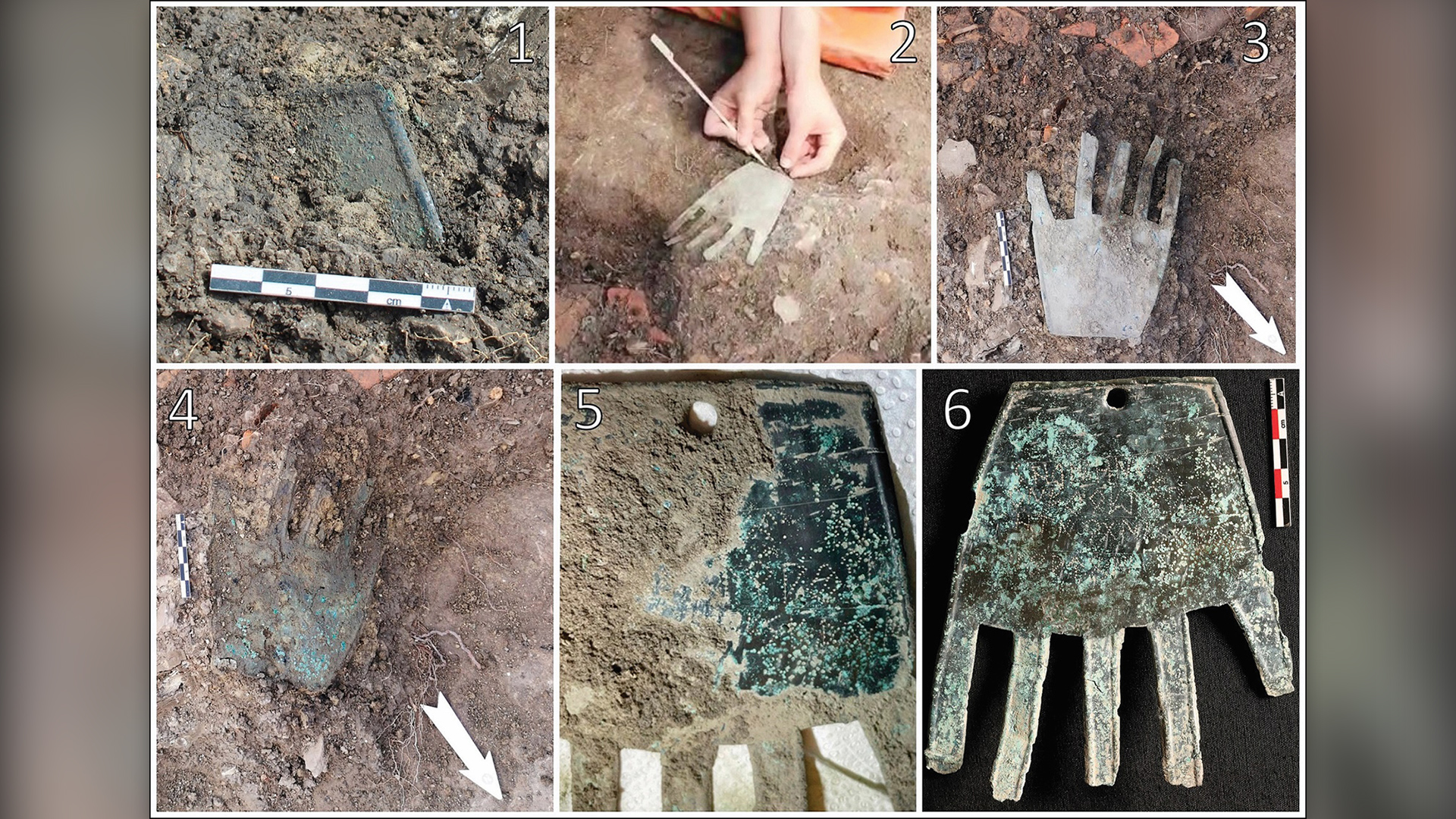

An inscription carved into a 2,100-year-old hand-shaped amulet from northeastern Spain seems to be related to Basque and may be a rare example of an ancient language spoken in Europe more than 5,000 years ago.

In a new study, published Tuesday (Feb. 20) in the journal Antiquity, researchers revealed that the inscription is the oldest and longest ever found in a Vasconic language, a group of languages that includes modern Basque. Until now, the only known ancient Vasconic texts were mainly from a few words written on coins from the region, the researchers said.

Archaeologists unearthed the amulet in 2021 at the Iron Age site of Irulegi, in Spain's Navarre region. The first word of the inscription, which uses the Latin alphabet, is "sorioneku" or "sorioneke" — similar to the modern Basque word "zorioneko," meaning "good fortune." Because of this similarity, the researchers think the meaning of the words are the same, and that the amulet may have hung outside a building as a good luck charm.

Related: 5,000-year-old mass grave of fallen warriors in Spain shows evidence of 'sophisticated' warfare

"The hand would've had a ritual function, either to attract good luck or as an offering to an indigenous god or goddess of fortune," study lead author Mattin Aiestaran, an archaeologist at the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, said in a statement.

While only the first word of the inscription has been deciphered, the researchers have identified at least five words, written with 18 characters on the "palm" of the hand.

Archaeological finds suggest that the settlement at Irulegi existed from the first millennium B.C. until the first century B.C., when it was likely burned down during the Sertorian War from 80 to 72 B.C. between rival factions of Romans, who ruled much of the Iberian Peninsula at the time, the researchers said. The use of Latin characters shows the Romans were present in the area when the amulet was made.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lost language

Basque is the only surviving Vasconic language. Its origins are unclear, but linguists think it derived from ancient Vasconic languages spoken in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula.

Most modern European languages — including those with Germanic, Celtic, Latin and Slavic roots — belong to the Indo-European family of languages, which originated with the languages of the Indo-European peoples who arrived from the Eurasian steppe between 5,000 and 10,000 years ago. As a result, they share some similarities in words and grammar, even though they appear very different.

But linguists consider modern Basque a language "isolate" because it is unlike any other spoken languages. It is similar, however, to the now-extinct Aquitanian language spoken in northeastern Spain and southwestern France before the arrival there of the Romans.

An idea called the Vasconic substrate hypothesis suggests that Vasconic languages influenced place names across Western Europe, and that some Vasconic words can be found in several Western European languages. Some linguists have suggested this may be evidence that Vasconic languages were widespread before the Indo-European arrival.

However, the idea has been rejected by many other linguists, who argue that this is probably the result of Indo-European words being adopted into Vasconic languages, and that the hypothesis otherwise lacks substantial evidence.

According to the researchers, the Irulegi inscription is the starting point for a "linguistic map" showing the connections between its ancient Vasconic language; other ancient languages of the Iberian Peninsula; and modern Basque.

Linguist Peter Trudgill, the author of "Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society" (Penguin, 2001) and formerly a professor at Switzerland's University of Fribourg, said the latest study was "very convincingly argued, and exciting."

The inscription on the bronze hand was "a true window on the past," Trudgill, who wasn't involved in the study but has studied Vasconic languages, told Live Science in an email.

"We really have learnt something new," he said. "We know so little about Vasconic languages and peoples that this is genuinely a very valuable contribution.

Linguist and Basque specialist Roslyn Frank, a professor emeritus at the University of Iowa who also wasn't involved in the study, said she was pleased to see researchers discussing the artifact, even though the meaning of the entire text remained unclear.

"In my opinion, far too little attention is paid to the Basque language and culture, given that it represents a doorway to Europe's past," she told Live Science in an email.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus