5,000-year-old mass grave of fallen warriors in Spain shows evidence of 'sophisticated' warfare

A new analysis of a mass grave from Neolithic Spain reveals that the site wasn't a burial ground from a massacre, but of fallen warriors.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Over 5,000 years ago, men, women and children with head trauma and arrow wounds were buried in a mass grave in Spain. Now, archaeologists have teased apart this tangled web of skeletons, revealing new evidence of ancient warfare, a new study finds.

The San Juan ante Portam Latinam (SJAPL) rock shelter, located in the town of Laguardia in northern Spain, was first excavated in 1991. More than 300 skeletons, radiocarbon-dated to 3380 to 3000 B.C., were found in one mass burial, many of them interwoven and in odd positions. Excavators also discovered dozens of flint arrowheads and blades, along with stone axes and personal ornaments.

Researchers initially concluded that they'd found evidence of a Neolithic massacre. But a new analysis of the SJAPL skeletons has revealed that these people were most likely killed in separate raids or battles over a period of several months or years.

Related: Why were dozens of people butchered 6,200 years ago and buried in a Neolithic death pit?

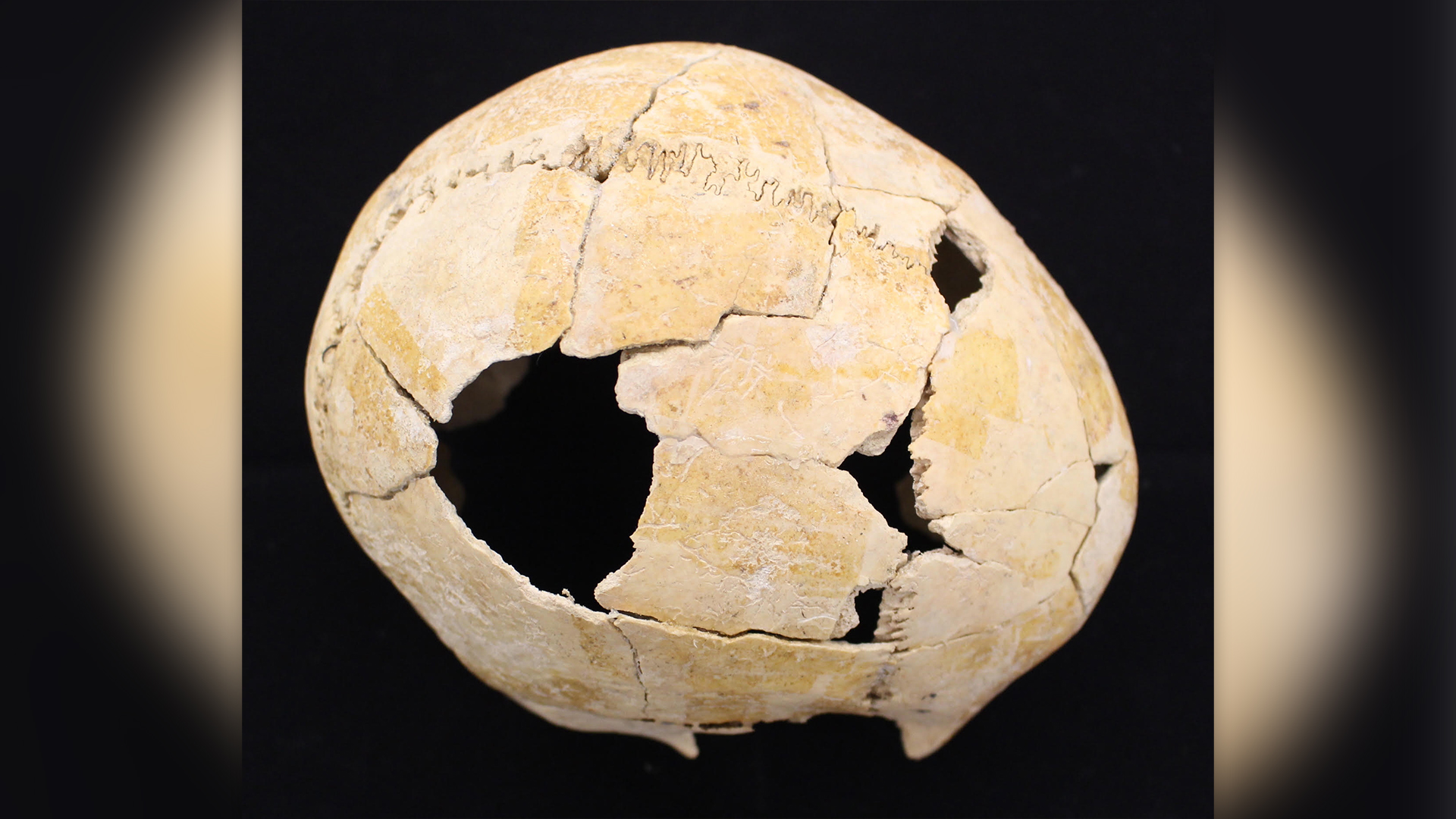

In a study published Thursday (Nov. 2) in the journal Scientific Reports, first author Teresa Fernández-Crespo, an archaeologist at the University of Valladolid in Spain, and her team describe the healed and unhealed injuries on the SJAPL skeletons. They found a total of 107 cranial injuries, most of which were located on the top of the skull and likely correspond to blunt-force trauma, such as blows from stone maces or wooden clubs. Nearly five times as many males as females suffered cranial trauma, the researchers found.

Injuries on the rest of the skeletons were also examined. The team discovered 22 instances of trauma — mostly spiral or V-shaped fractures — affecting the limbs, as well as 25 injuries to other parts of the body. Like the skull injuries, these seem to have disproportionately affected men, who were nearly four times as likely as women to have evidence of bodily trauma. Arrowhead injuries were also strongly linked to male skeletons, suggesting men were more often exposed to long-range violence than women were.

All told, adolescent and adult males buried at SJAPL accounted for 97.6% of unhealed trauma and 81.7% of healed trauma recorded in skeletons whose biological sex could be estimated. This suggests, according to the study authors, that the mass grave represents "one or more 'war layers' resulting from battles and/or raids where the involvement of males was dominant."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We think we are seeing the result of a regional inter-group conflict" at SJAPL, Fernández-Crespo told Live Science in an email. "Resource competition and social complexity could have been a source of tension, potentially escalating into lethal violence" between communities, she said.

These Late Neolithic communities — each of which consisted of a few hundred people — comprised mostly farmers, who cultivated wheat and barley and tended to domesticated herds of sheep, cattle and pigs. But additional evidence of illness and stress that the team found on the Neolithic skeletons suggests that food scarcity may have affected the people and potentially been a consequence of the violence.

"This research presents a convincing case for interregional conflict where male combatants died in battle," Ryan Harrod, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Alaska Anchorage who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "The fact there were more nonlethal compared to lethal injuries on the 338 individuals," Harrod said, shows that many people healed from their injuries, "which might indicate that the regional clashes were not epic battles or warfare."

The combination of evidence from SJAPL, including traumatic injuries from arrows and skeletal indicators of poor health, coupled with high population pressure and the presence of different cultural groups, may have created a metaphorical powder keg that erupted 5,000 years ago, resulting in what the researchers have characterized as "a more sophisticated and formalized way of warfare than previously appreciated in the European Neolithic record."

Editor's note: Updated at 2:19 p.m. EDT to note that food scarcity may have been a consequence of the violence, not a trigger for it as was previously stated.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus