1st-ever ancient case of Turner syndrome, with just 1 X chromosome instead of 2, found in ancient DNA

A new DNA technique has detected evidence in Iron Age skeletons of Turner, Klinefelter and Down syndrome.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Roughly 2,500-year-old DNA has revealed the first ancient person on record with Turner syndrome, a genetic condition in which a person has just a single X chromosome rather than two, a new study finds.

The individual, who died when they were 18 to 22 years old, likely hadn't gone through puberty, an analysis of the bones revealed. A further investigation of the remains revealed that the individual had mosaic Turner syndrome, as some cells had just one X chromosome while others had two.

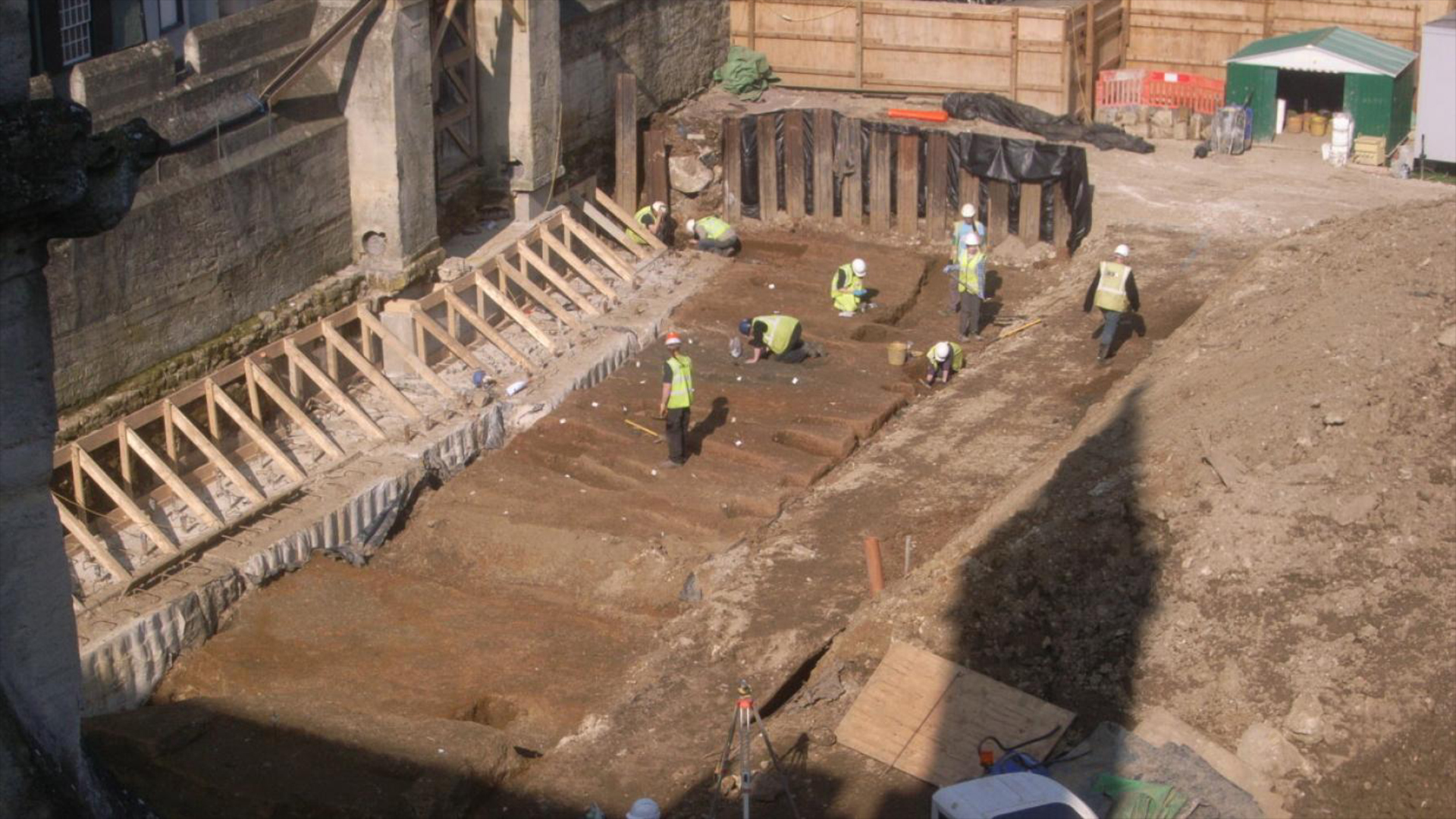

The research looked at historical DNA gathered in the Thousand Ancient British Genomes project — a database of DNA being collected from skeletons in the U.K. The team identified a total of six people with sex chromosomal conditions, according to a study published Jan. 11 in the journal Communications Biology.

The researchers made the discoveries after developing a computational method to find atypical numbers of chromosomes in DNA from skeletons.

Related: Europeans' ancient ancestors passed down genes tied to multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's risk

The individual with Turner syndrome, who died in the early Iron Age (750 to 400 B.C.) likely had a partially missing second X chromosome. This condition can often lead to symptoms and characteristics such as shorter-than-average height, cardiac defects and small or absent ovaries, leading to fertility issues.

Of the other five people with aneuploidies, or genetic disorders in which a person doesn't have 46 chromosomes, three individuals showed signs of Klinefelter syndrome — a genetic condition in which a person has an XXY set of sex chromosomes. Of these three individuals, one died in the Iron Age (circa 750 B.C. to A.D. 43), one in the high Middle Ages (around A.D. 1050 to 1290) and one in the early 19th century. Klinefelter syndrome often stunts the growth of a person's testicles, leading to lower testosterone levels, lower muscle mass, less body hair and larger breast tissue than typical XY individuals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The three skeletons identified with this condition were buried in ways typical for their times, according to the study, showing that "their burials did not reveal any differences in how they were perceived by their contemporaries," the researchers wrote.

Another male individual from the early medieval period (eighth century) had an extra Y sex chromosome, known as XYY syndrome. Most people who have XYY chromosomes have no physical features that are different than people with XY chromosomes, other than often being taller than average.

The researchers also identified a male infant from Iron Age Britain who had Down syndrome. This condition can result in neurodevelopmental problems, and identifying skeletons with the syndrome "can provide insights into care within ancient societies, as well as how people with these conditions, which have characteristic physical manifestations, were perceived by their peers," the researchers wrote in the study.

Although the number of people with chromosomal differences revealed in this study is small, the researchers' new method gives them the opportunity to observe genetic diversity to "provide another layer of information that can contribute to a more detailed reconstruction of the human past," they wrote in the study.

In particular, making it easier to study variations in sex chromosomes in ancient DNA can help move the field of skeletal analysis beyond binary sex estimations and into a more complex understanding of social gender.

"It is difficult to know an ancient individual's conception of their own gender identity, and gender norms in the past may not align with those of the present day," the researchers wrote in their study. "It is possible that an elevated proportion would have been seen to transgress gender boundaries."

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus