11,000-year-old submerged stone wall discovered off Germany was once used to trap reindeer

The wall may be among the oldest hunting structures on Earth and one of the largest Stone Age structures ever found in Europe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An underwater stone wall discovered in the Baltic Sea near Germany was built about 11,000 years ago for hunting reindeer when the location was dry land, a new study indicates.

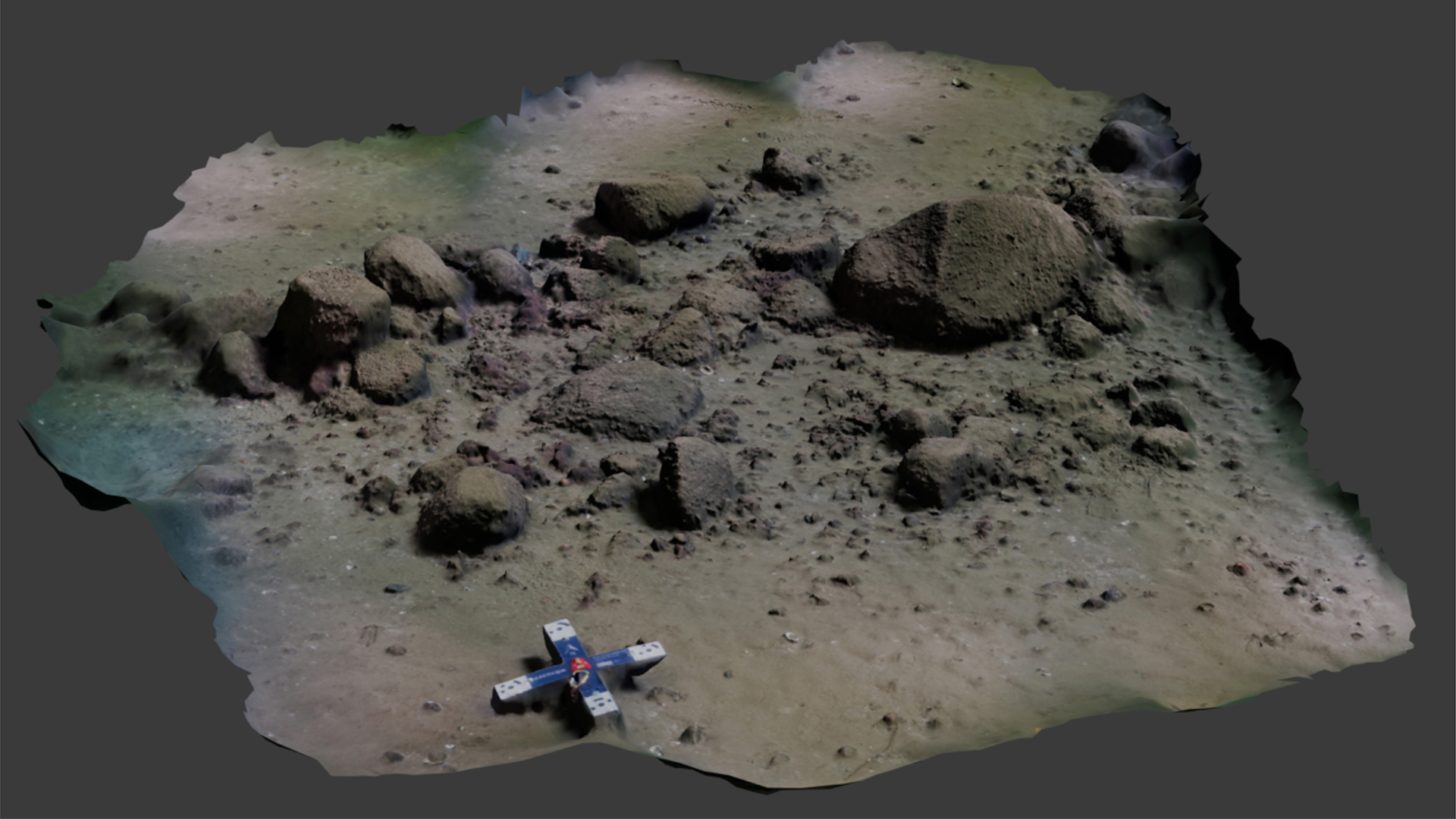

The researchers suggest the local prehistoric people built the wall; its remaining parts were crafted from 1,670 stones and stretch about two-thirds of a mile (975 meters) long, stand 3 feet (1 m) tall and are 6.5 feet (2 m) wide. The team discovered the wall via sonar and dives to the location, which is at a depth of about 70 feet (21 m) and roughly 6 miles (10 kilometers) east of Rerik, Germany, in the Bay of Mecklenburg.

The wall may be the largest of its kind from the early Holocene (11,700 years ago to present) in Europe, the researchers said in the study. Based on similar prehistoric walls — including the ancient "desert kites" found in the Middle East — the authors propose that it was built on dry land by hunter-gatherers to drive wild animal herds into corrals where they could be killed. They also suggest that the wall in the Bay of Mecklenburg was used to hunt reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), which was a common species in that part of Europe at the time.

But changing sea levels caused by melting ice sheets after the last ice age flooded the area about 8,500 years ago, along with other parts of the modern Baltic and the "Doggerland" region that joined Britain and the European continent.

Related: 7,000-year-old cult site in Saudi Arabia was filled with human remains and animal bones

Hunting wall

Scientists detected the wall almost by accident in 2021, during a boat trip into the Bay of Mecklenburg to teach marine geophysical techniques to students.

"It was a bit out of the blue," Jacob Geersen, a marine geophysicist at Kiel University in Germany, told Live Science. "We did not look for the structure because we did not know it was there. But we resolved it on the seafloor from our multibeam echosounder data."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers have now mapped the wall using sonar equipment on boats and on an autonomous underwater vehicle, and researchers have made dives to different sites along its length. Those investigations and sediment samples from the seafloor around the structure indicate that it was built on purpose on dry land, rather than being a natural feature of the now-submerged landscape.

Geersen and Marcel Bradtmöller, a prehistorian at the University of Rostock in Germany, are the co-lead authors of the study about the discovery, published Monday (Feb. 12) in the journal PNAS.

Bradtmöller explained that the wall seems to have been built beside the shore of an ancient bog or lake that would have prevented the herd animals from escaping in that direction.

The date the wall was built isn't precisely known, he said, but it's thought that reindeer went extinct in the area about 9,000 years ago, a few hundred years before it was flooded by the sea.

As well as mapping the wall, the researchers hope to find buried artifacts along its length that could reveal more about the wall's origins and use. They suggested that parts of the wall could have been "blinds" where people tasked with killing the animals could have hidden so as not to scare away a panicked herd.

Submerged lands

In part due to the low-oxygen environment of water, submerged structures are often well preserved. But they can be challenging to study, the authors noted. The Bay of Mecklenburg wall, however, lies in relatively protected waters along the Baltic coast, unlike structures in the Doggerland region of the North Sea, where storms and high waves are common, Geersen said.

As well as better preserving the structure, the milder waters make it easier to investigate the wall, he said; the researchers expect to return to the site in a few months.

Vincent Gaffney, an archaeologist at the University of Bradford in the U.K. who wasn't involved in the study but is a key investigator of Doggerland, told Live Science that the wall — if it's confirmed to be a human-made structure — "clearly demonstrates that our coastal shelves, much of which were habitable prior to sea-level rise following the last glaciation, are likely to have preserved evidence for prehistoric lifestyles rarely preserved on land."

Many now-submerged sites are being developed for coastal or offshore structures, so the discovery shows "the need to explore these areas, which are currently Terra Incognita [Latin for unknown land]," he said in an email.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus