Move over, python — this tiny snake holds the record for swallowing the largest prey whole relative to body size

The Gans' egg-eater, an African snake, can swallow eggs whole despite its small size.

Snakes are known for gulping down truly gargantuan meals. However, one species of serpent outpaces them all, consuming the largest prey relative to its size of any known snake — and it's not the python.

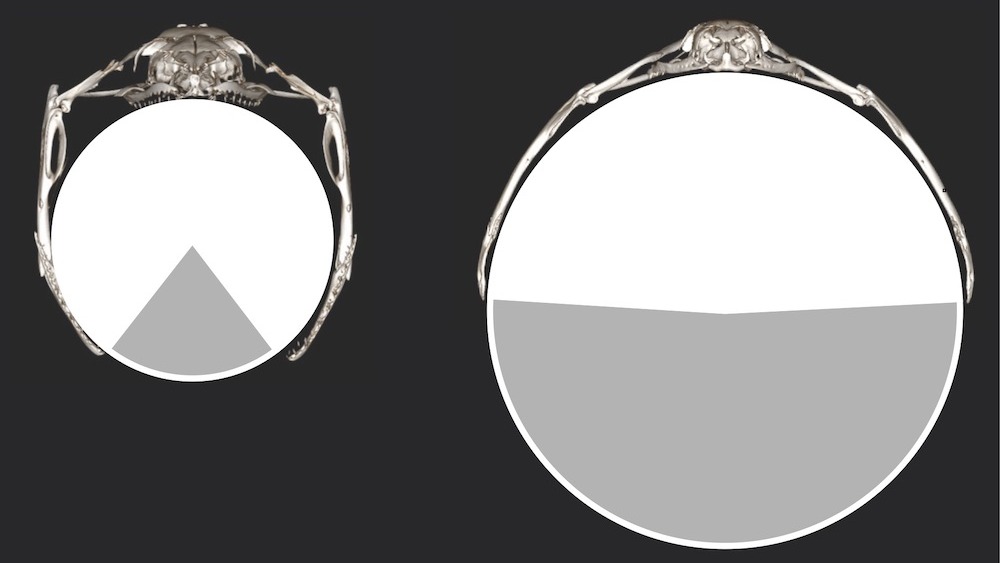

Known as the Gans' egg-eater (Dasypeltis gansi), this skinny, nonvenomous African snake has a gape so big that it can swallow spherical bird eggs whole despite its diminutive size, which tops out at about 40 inches (102 centimeters) in length. Its ability to dine on prey much larger than itself comes from the stretchy skin that connects the snake's left and right lower jawbones, allowing it to open its maw exceedingly wide, according to a study published Aug. 8 in the Journal of Zoology.

"They seem to be the world record holder for the size of their gape and their overall size," study author Bruce Jayne, a biologist and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cincinnati, told Live Science. "Their ability is even more extreme than Burmese pythons'."

In fact, the Gans' egg-eater can devour prey three to four times larger than snakes that are classified as "generalists," such as the black rat snake (Pantherophis obsoletus), whose diet, in addition to eggs, includes things like rodents and amphibians, according to a statement.

Related: The biggest snake in the world (and 9 other giant serpents)

Jayne put the Gans' egg-eater's egg-swallowing skills to the test — even capturing its eating abilities on video — to investigate whether it had the largest gape relative to its size.

In the lab, Jayne fed a Gans' egg-eater a quail egg. After swallowing it whole, the snake contorted its spine to crack the egg, eventually regurgitating only the broken eggshell. (The entire process lasted 15 to 30 minutes.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fact that teeth are "nearly absent in the species" proves beneficial, since it "helps the liquid contents of the egg not to be expelled" as the snake swallows it, Jayne said.

"Swallowing a relatively benign object that is hard and smooth is difficult to do," Jayne said. "Having teeth would cause [the egg's contents] to splash out [of its mouth] if it's punctured by needle-like structures like teeth."

This isn't the first time Jayne has tested snakes' gape sizes. Last year, he studied how wide Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) could open their mouths. He found that they, too, have an impressive ability to dine on larger prey; in the wild, they've been known to swallow deer whole.

While that's no doubt impressive, a Gans' egg-eater is capable of consuming prey with a cross-sectional area that's more than twice that of a Burmese python of similar weight, according to the study.

Jayne said this "superpower" is a means for survival, since most bird eggs are "stout" and "spherical," like Ping-Pong balls, whereas mice and rats are typically more elongated, the former proving more challenging for other snake species with smaller mouths. The Gans' egg-eater's extreme gape evolved so that the snake could specialize in eating prey that has "a modest amount of mass per cross-sectional area," according to the statement.

"One of the benefits of eating eggs is that they don't fight back," Jayne said. "D. gansi has a prey resource that is immobile."

Editor's note: This article has been corrected to say mice and rats are more elongated than bird eggs.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus