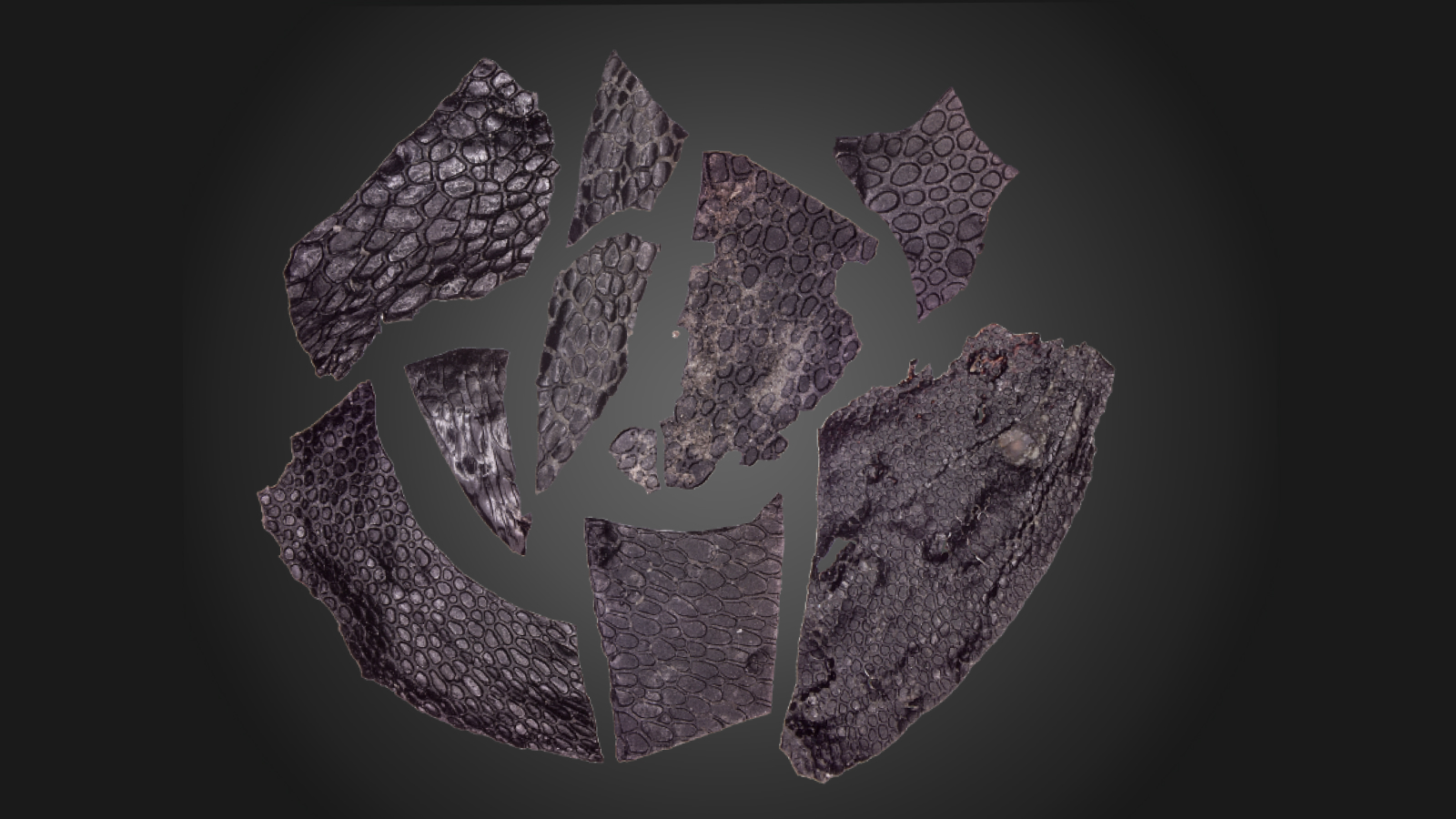

Mummified skin from creature that lived 290 million years ago is older than the dinosaurs

Crocodile-like skin from a reptile is 130 million years older than the previous record for fossilized skin, researchers say.

Crocodile-like skin belonging to an early species of reptile is the oldest fossilized skin ever discovered, dating back almost 290 million years — 130 million years older than the previous record holder.

The skin, dating from the Paleozoic era (541 million to 252 million years ago), has similar features to that of other ancient reptile species, with pebble-like, non-overlapping scales, which most closely resemble the extinct Cretaceous (145 million to 66 million years ago) dinosaur Edmontosaurus and crocodile skin. Hinged regions between the epidermal scales resemble the skin structures found in snakes and worm lizards, paleontologists noted in a new study.

"It was mind blowing when we realized this was technically the oldest piece of a proper mummified skin," study co-author Ethan Mooney, a University of Toronto paleontology graduate, told Live Science. "Impressions of skin are rare in the fossil record, but more common than proper mummified skin. "Our skin cast (which is mummified skin), is 130 million years older than the oldest example of proper mummified skin, most of which comes from dinosaurs."

The previous oldest confirmed skin fossil came from a dinosaur, lead author Robert Reisz told Live Science. He added that there is another fossil from Russia that is 21 million years younger, but the specimen needs to be restudied to confirm it is skin.

According to the study, published Jan. 11 in the journal Current Biology, the skin fossil is the oldest known example of a preserved epidermis — the outermost layer of skin found in terrestrial reptiles, birds and mammals. The structure could have been vital to species' transition and survival from aquatic to fully terrestrial environments, because it protected their organs from the elements.

Related: Megalodon tooth found on unexplored seamount 10,000 feet below the ocean's surface

The tiny fingernail-size skin fossil was found preserved in clay sediments in Richards Spur limestone cave system in Oklahoma, along with other specimens. Although skin and soft tissues are rarely fossilized, researchers say the cave system’s complex composition of fine clay sediments combined with oil seepage in an oxygenless environment likely slowed decomposition and preserved the sample.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When researchers examined the fossil under a microscope, they found epidermal tissues that are commonly found in the skin of amniotes — a terrestrial vertebrate group consisting of reptiles, birds and mammals that evolved from amphibian ancestors during the Carboniferous period.

At the time this creature lived, dinosaurs were yet to emerge and animals consisted of four-legged vertebrates which were fish-like in appearance. According to a study from 2009, these early tetrapods would have resembled crocodiles, lizards, eels and snakes.

Mooney said these ancient ancestors would have looked "very reptilian if you saw them today," adding that the "mummified skin and associated impressions likely show us what the skin would have been like in these ancestral reptiles."

However, as no skeleton or other remains were found, researchers say it isn't possible to identify the species of animal or even the part of the body the skin originated from.

Mooney said discovering fossilized skin resembling that seen in living animals today shows it was "critical for their success on land." This early skin, and the novel structures within, enabled creatures to move from aquatic environments to terrestrial habitats, eventually leading to the evolution of birds, mammals and reptiles, the authors wrote.

Carys Matthews is a freelance writer for Live Science and has a passion for the natural world. Most recently the group digital editor of BBC Wildlife and BBC Countryfile Magazine, she writes about the outdoors, nature and health and fitness. Prior to this she has worked for a number of sports and environmental titles in the U.K.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus