Colossus the enormous 'oddball' whale is not the biggest animal to ever live, scientists say

Researchers have re-estimated the weight of Perucetus colossus — a bizarre species that lived 39 million years ago — and claim it's much lighter than a blue whale.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A weird extinct whale with a plump body and tiny limbs isn't the heaviest animal to ever live after all, a new study has claimed, bringing with it a whale of a debate.

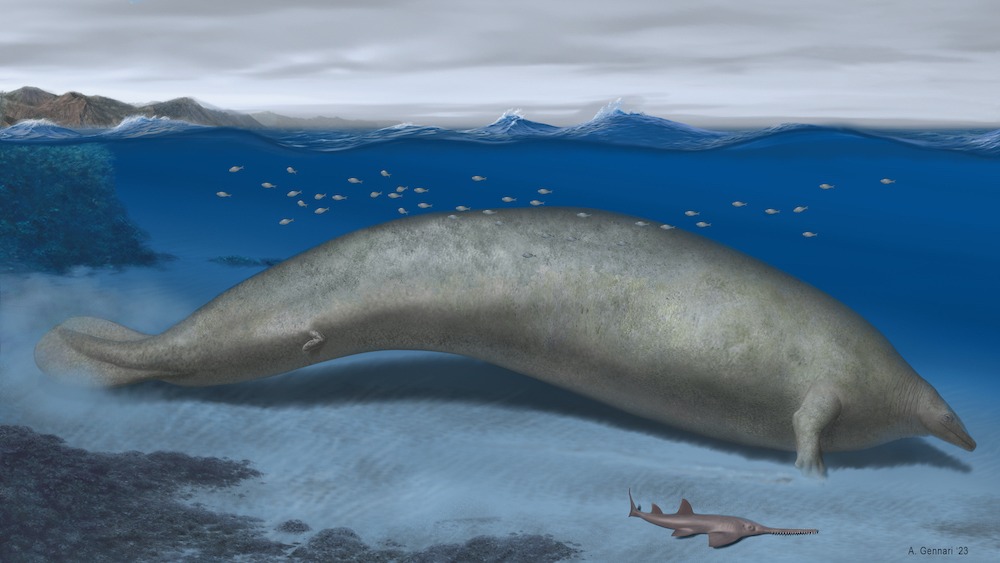

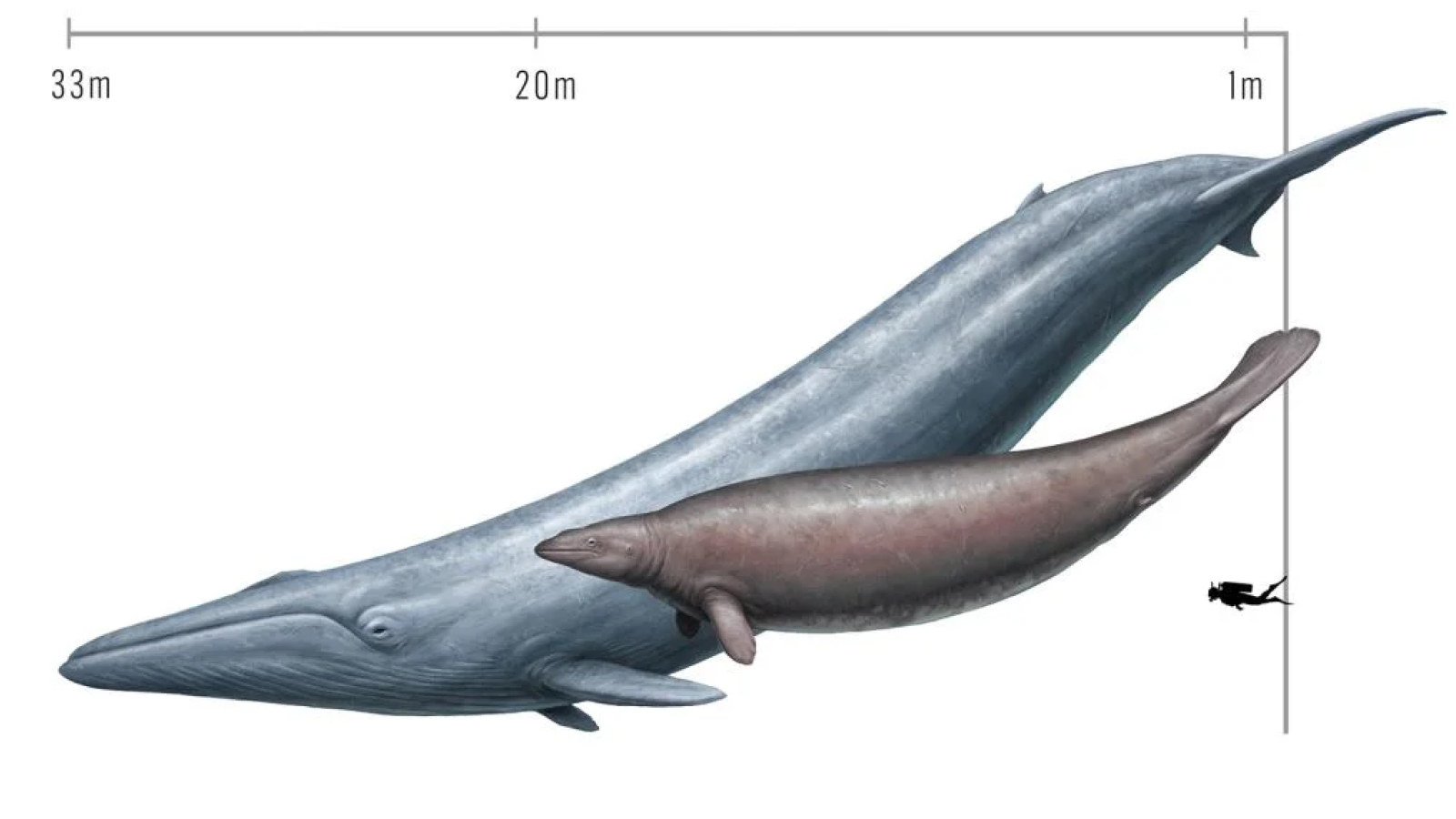

Last year, a team of researchers unveiled Perucetus colossus, a 39-million-year-old whale from Peru with an estimated body mass of 187,000 to 750,000 pounds (85,000 to 340,000 kilograms) — potentially double that of a blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus).

But now, the authors of a new study, published Feb. 29 in the journal PeerJ, have concluded the original research team massively overestimated the weight of the animal, claiming it would have been too dense to stay up in water if it was as heavy as their upper estimate suggested.

"With their weight, this animal could not stay at the surface," lead author Ryosuke Motani, a paleobiologist at the University of California, Davis, told Live Science. "This animal would have been swimming vertically up all the time, which is impossible."

Motani and his colleague, Nicholas Pyenson, the curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, cross-examined the original paper, created 3D models of P. colossus and a blue whale, and made different assumptions about how to calculate weight.

Related: Stunning 240 million-year-old 'Chinese dragon' fossil unveiled by scientists

They found that P. colossus was more like 130,000 to 250,000 pounds (60,000 to 113,000 kg) and blue whales can be up to 600,000 pounds (270,000 kg).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The lead author of the first P. colossus study, Eli Amson, a paleontologist and curator of fossil mammals at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History in Germany, told Live Science that he stands by all of his team's original conclusions, and their wide range was a conservative estimate.

Amson reviewed the new study prior to publication with another author from the 2023 study, so they knew it was coming. He noted that the study didn't find factual inaccuracies in their research, but merely made different estimates based on their data.

"We are estimating the body mass of an extinct animal that is known from a very fragmentary skeleton, so of course there's quite a lot of room for using this or that method," he said.

Amson added that the debate mostly boils down to how whale-like this ancient cetacean was.

"When you look at the blue whale, it's gigantic, obviously, but it has a very sleek profile," he said. "If you compare other marine mammals like manatees and dugongs, they have a much chubbier body outline."

P. colossus had large and extremely heavy bones. They weren't spongy or hollow like those of most mammals. Their bones also had extra growth on the outside, called pachyostosis, like living manatees, according to a statement released by the University of California, Davis. Extra bone weight helps counter the buoyancy gained from having lots of body fat and blubber, which forces the animal upwards in the water.

Amson and his colleague flagged several concerns with the new study prior to its publication, including that the authors used an artist reconstruction from their original paper to help estimate volume and mass, which Amson said wasn't designed based on the creature's volume.

Motani told Live Science that the exactness of the reconstruction didn't matter that much because it couldn't have been "much fatter" than the reconstruction.

A complete skeleton with a skull and teeth could help settle the debate. For now, however, disagreement between the researchers is likely to continue.

Either way, the species is still a "complete oddball," Amson said, and demonstrates gigantic animals were living on the coast when they had previously been associated with offshore environments.

"This is an exceptional new species that changes our understanding of cetacean evolution," he added.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus