Ancient giant rhino was one of the largest mammals ever to walk Earth

It was as heavy as four African elephants.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The remains of a 26.5-million-year-old giant, hornless rhino — one of the largest mammals ever to walk Earth — have been discovered in northwestern China, a new study finds.

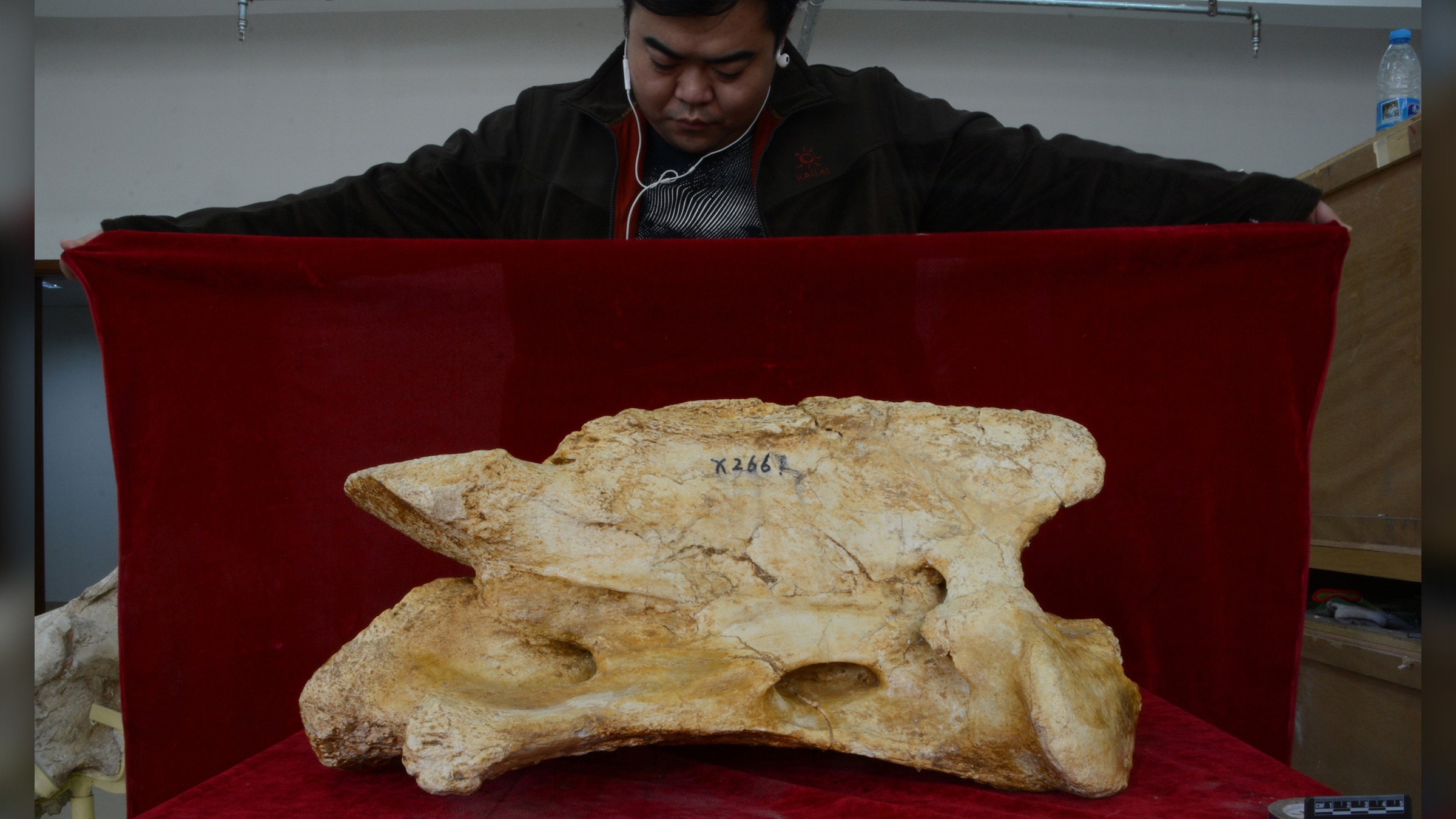

The newly identified species, Paraceratherium linxiaense — named after its discovery spot in the Linxia Basin in Gansu province — towered over other animals during its lifetime. The 26-foot-long (8 meters) beast had a shoulder height of 16.4 feet (5 m), and it weighed as much as 24 tons (21.7 metric tons), the same as four African elephants, the researchers said.

The new species is larger than other giant rhinos in the extinct genus Paraceratherium, said study lead researcher Deng Tao, director and professor at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. A new family tree analysis of Paraceratherium species, including P. linxiaense, reveals how these ancient beasts evolved as they migrated across Central and South Asia at a time when the Tibetan Plateau was lower than it is today, Tao told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: These animals used to be giants

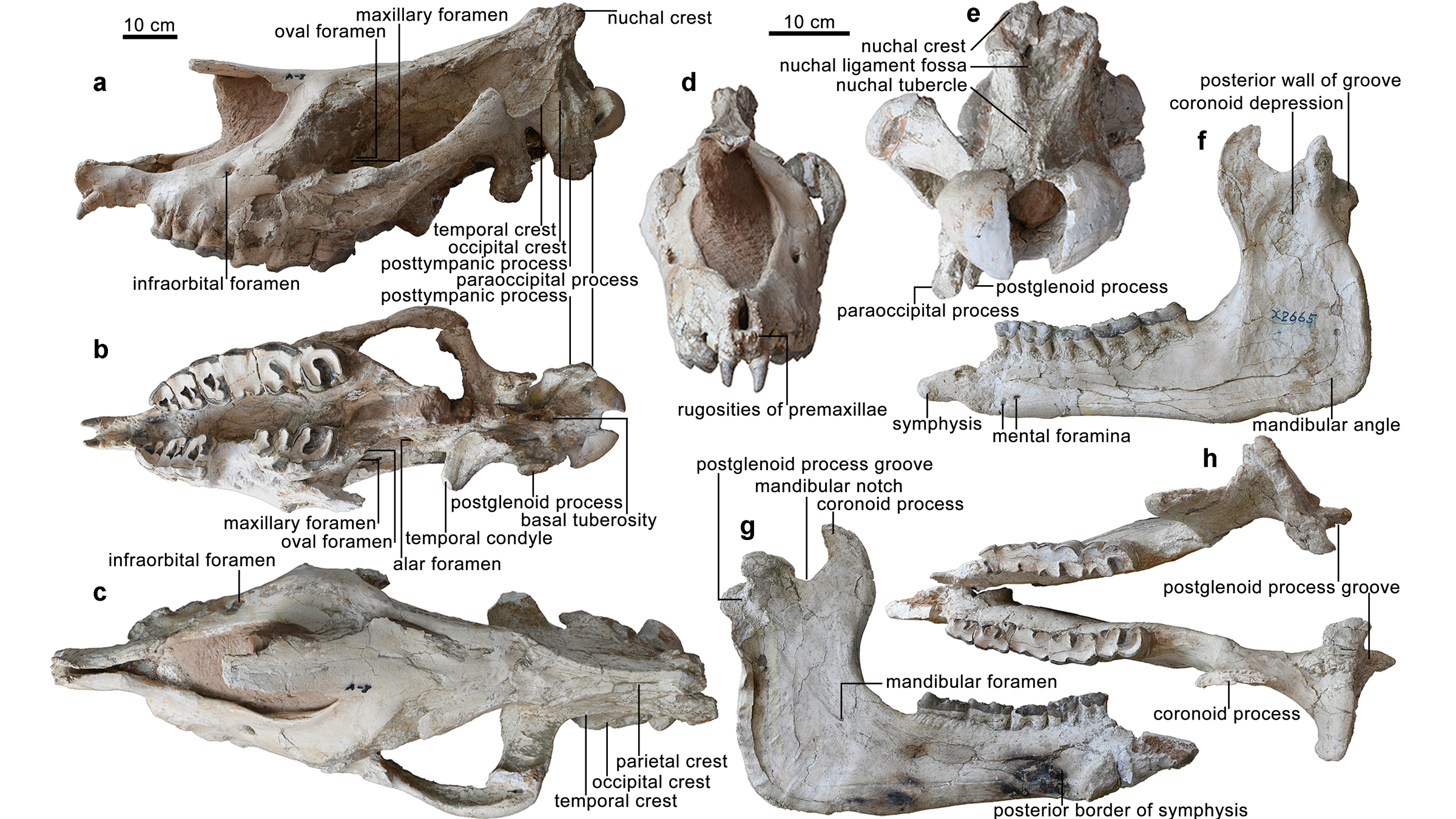

Researchers have known about the fossil trove at Linxia Basin, located at the northeastern border of the Tibetan Plateau, since the 1950s, when farmers there began discovering "dragon bones," Tao said. Digs in the 1980s revealed rare, but fragmentary giant rhino fossils. That changed in 2015, with the discovery of a complete skull and jaw of one giant rhino individual, and three vertebrae from another individual, both dating to the late Oligocene epoch (33.9 million to 23 million years ago).

When the researchers saw the fossils, the bones' completeness and "huge size … [were] a great surprise for us," Tao said. An anatomical analysis, in addition to the fact that the fossils were larger than those from other known species in the Paraceratherium genus, revealed that they belonged to a previously unknown Paraceratherium species.

The skull and jaw bones showed that P. linxiaense had a giant, 3.7-foot-long (1.1 m) head; a long neck; two tusk-like incisors that pointed downward; and a deep nasal notch, indicating that the animal had a trunk like that of a tapir. The giant rhino likely wrapped its trunk around branches so it could easily strip off leaves with its front teeth, Tao said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

P. linxiaense stood on four long legs that were good for running, and its head could reach heights of 23 feet (7 m) "to browse leaves of treetops," Tao said.

Family tree

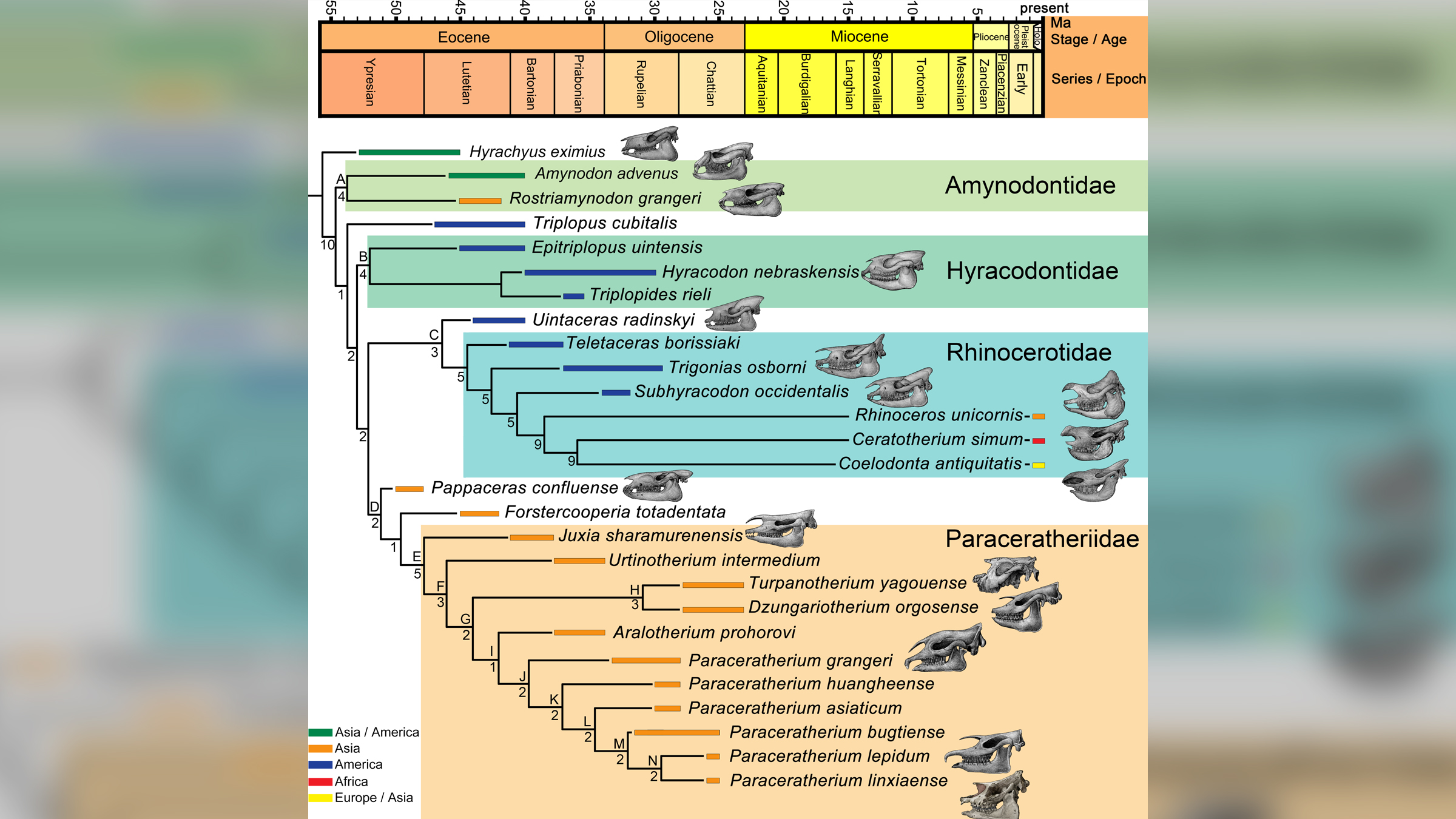

Most species within Paraceratherium lived in Central Asia (what is now Mongolia and Kazakhstan), but one far-flung species, P. bugtiense, lived farther south, in what is now western Pakistan. This distant location puzzled scientists, so Tao and his colleagues set out to see if they could discern this species' relationship with other Paraceratherium species, including the newfound P. linxiaense.

The team created the rhino ancestor's family tree by analyzing the anatomy of 11 giant rhino species and 16 other animal species in the superfamily Rhinocerotoidea, including two living rhinos. The analysis revealed that the Mongolian giant rhino (P. asiaticum) dispersed westward to what is now Kazakhstan, and its descendant lineage expanded to South Asia and evolved into P. bugtiense during the early Oligocene, Tao said.

At that time, Central Asia was arid, while South Asia was relatively humid, with a mosaic of forested and open landscapes, where giant rhinos likely browsed for food, Tao said.

During the late Oligocene, tropical conditions allowed giant rhinos to trek northward, back to Central Asia. It appears that the far-flung P. bugtiense crossed the Tibetan region, and evolved into two closely-related species: the newly found P. linxiaense, known from China, and P. lepidum, known from China and Kazakhstan.

Given that some of the world's largest mammals took this impressive journey, it's likely that the Tibetan region "was still not uplifted as a high-elevation plateau" at that time, Tao said. It may have been under 6,600 feet (2,000 m) during the Oligocene, and "giant rhinos could have dispersed freely through this region," he said.

The study was published online Thursday (June 17) in the journal Communications Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus