Great white-shark-sized ancient fish discovered by accident from fossilized lung

It belongs to the mysterious coelacanth family of fishes.

A 66 million-year-old fossilized lung from a previously unknown species of ancient fish, as large as a great white shark, has recently been uncovered in Morocco.

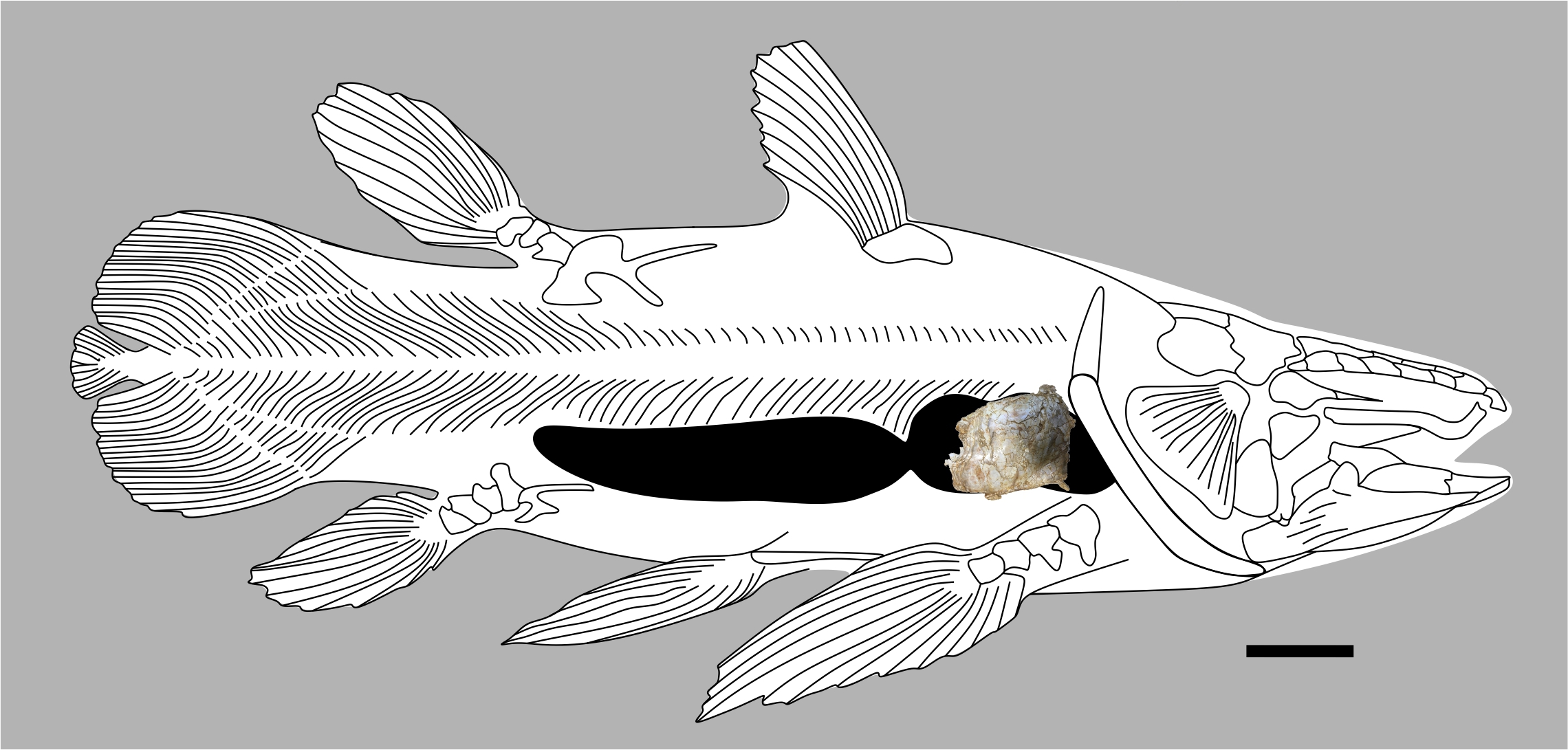

Researchers believe the fish was a much larger member of the coelacanths, an Order of fish nicknamed the 'living fossils that were thought to be extinct until a live specimen was found in 1938. Given the size of the newfound lung, this particular coelacanth would have been 17 feet (5.2 meters) long, according to the researchers.

The fossilized lung was part of a large slab, uncovered in phosphate beds in Oued Zem in Morocco, which contained several other bones belonging to pterosaurs. The bones confirm that the coelacanth dates back to the end of the Cretaceous period 66 million years ago, just before the dinosaurs became extinct.

Related: T. rex of the seas: A mosasaur gallery

"It is absolutely enormous; it's a giant coelacanth, in a place we have never found them before" said study co-author David Martill, a paleontologist at the University of Portsmouth in England.

The new discovery sheds light on one of the most mysterious fish groups to ever swim in the oceans, but it also raises questions about what happened to them.

A lucky find

A private pterosaur collector in London bought the fossil slab from a seller in Morocco and originally mistook the fossilized fish lung as part of a pterodactyl skull. But on closer inspection, he was unsure, so he contacted Martill to get his professional opinion.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"He sent me a bunch of pictures, and I really didn't know what it was," Martill told Live Science. "But I really didn't think it was part of the pterosaur."

However, after visiting the fossil slab in person, Martill knew exactly what he was looking at. "I realized that instead of being one bone, it was actually hundreds of very thin sheets of bone," Martill said.

The fossil lung was somewhat barrel-shaped, but instead of the staves — the wooden planks that make up a barrel — lined up along the barrel, they were wrapped around it and overlapping.

"There's only one species that has a bone structure like that, and that's the coelacanth fish," Martill said. "They actually wrap their lung in this bony sheath, it's a very unusual structure."

Initially disappointed, the collector allowed Martill to separate the lung from the rest of the slab so it could be properly analyzed.

After discovering the fossilized lung, Martill teamed up with Brazlillian paleontologist Paulo Brito, a world leading expert in coelacanth lungs, from the State University of Rio de Janeiro. Brito confirmed Martill's suspicions and was "astonished" at the size of the specimen, according to a statement from the University of Portsmouth.

Previously discovered ancient coelacanths lived in rivers and had bodies extending between 10 and 13 feet (3 and 4 meters) in length; but the new unnamed species, which is thought to have lived in the open ocean, would have been much bigger. Modern-day coelacanths are smaller than both and reach around 6 feet (1.8 m) long.

"The coelacanth body plan has been pretty constant for the last few hundred million years," Martill said. "This one is just much bigger."

The collector has since donated the lung to the Department of Geology at Hassan II University of Casablanca in Morocco.

Mysterious end

One of the biggest mysteries surrounding the fossilized lung is where the rest of the coelacanth's massive body ended up. Martill's leading theory is that one of the large reptilian marine predators that dominated the Cretaceous oceans — such as plesiosaurs and mosasaurs — may have eaten it

"Coelacanths were slow-swimming fishes; this massive version would have been easy prey for these big predators," Martill said.

The researchers also found damage on the lung, which also suggests the fish was bitten by one of these massive predators.

Plesiosaurs and mosasaurs would have also regurgitated up large bones from their meals, like modern-day lizards do, which could explain why the lung ended up isolated with other bones from different animals. It would also explain why other coelacanths haven't been found in the area, as the fish may have been eaten hundreds of miles away and then regurgitated much later.

However, there is no way to prove that it died in this way.

"We haven't written about this in the paper, because the evidence is really tenuous," Martill said. "It's a good story but it's only one possibility."

What happened to the rest of the coelacanths is also a mystery. They completely disappear from the fossil record at the end of the Cretaceous period, which is what originally led scientists to think they were extinct. But live coelacanths found within the last century prove that at least one species managed to survive.

"We keep finding coelacanths up until the end of the Cretaceous, and then they just disappear," Martill said. "This is one of the last coelacanths before what we call the pseudoextinction."

It is possible that these giant coelacanths could still secretly roam the unexplored pockets of the deep sea today. But although he hopes this might be the case, Martill admitted: "the evidence of this happening isn't good."

The study was published online Feb. 15 in the journal Cretaceous Research.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.