Remains of more than 1,000 Indigenous children found at former residential schools in Canada

State-run boarding schools for Indigenous children operated in Canada between 1863 and 1998.

Unmarked graves that may hold the bodies of more than 160 Indigenous children were found this month on Penelakut Island, previously known as Kuper Island, in British Columbia, Canada.

Representatives of the Penelakut Tribe found the graves on the grounds of the former Kuper Island Industrial School, part of a network of mandatory state-run boarding schools for Indigenous children in Canada that subjected children to traumatic family separation, cultural erasure, and abuse. Penelakut Tribe members revealed the discovery in a newsletter that they shared online with neighboring tribes on July 8.

This grim finding is the latest such discovery in recent months. To date, more than 1,000 unmarked children's graves and remains have been identified at former Indigenous residential boarding schools in Canada. In addition to the Penelakut Island graves, unmarked burials at three more locations were detected by First Nations communities between May and July, using ground-penetrating radar scans at sites in British Columbia and Saskatchewan.

Related: 10 things we learned about the first Americans in 2018

On May 28, representatives of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Nation reported finding the remains of 215 children that were buried at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, run by the Catholic Church in British Columbia from 1890 until 1978, Reuters reported. Just a few weeks later, on June 24, the Cowessess First Nation announced that radar scans detected up to 751 unmarked graves at the site of the Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan, operated by the Catholic Church from 1899 to 1997, according to BBC News.

Then, on June 30, representatives of the Lower Kootenay Band, a member band of the Ktunaxa Nation, revealed that a recent search at the site of the former St. Eugene's Mission School — another Catholic institution in British Columbia, open from 1890 to 1970 — uncovered another 182 unmarked, shallow graves holding children's remains, CNN reported on July 2. (The Penelakut Tribe did not specify how the graves on the island were detected or if remains had been recovered, according to the CBC.)

Some of the children who died at Kamloops were as young as 3 years old, NPR reported, and accounts from former students at dozens of residential schools describe systematic abuse and neglect. Student deaths over decades numbered in the thousands, according to a government report produced in 2015 by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and children who died were often buried on school grounds so that authorities could avoid the costs of shipping remains home to their families.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

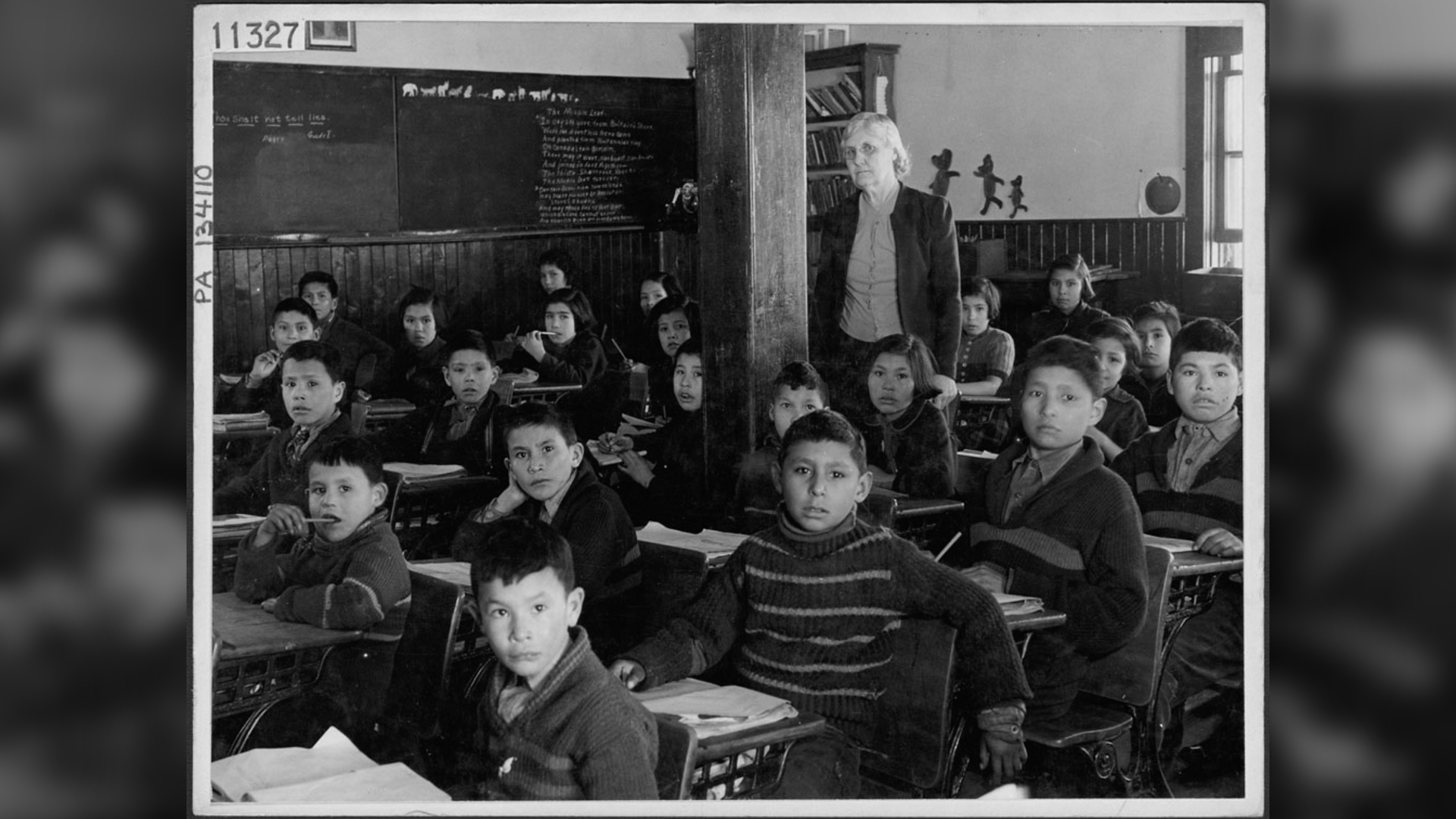

For almost 150 years in Canada — from 1863 to as recently as 1998 — more than 130 residential schools such as Kamloops, Marieval, St. Eugene's and Kuper Island were funded by the Canadian government, and until 1969 many of the schools were operated by Christian churches. These schools forcibly separated Indigenous children from their families and isolated them from their communities and cultures, according to Indigenous Foundations, a website for the First Nations Studies Program at the University of British Columbia.

During that time, more than 150,000 Indigenous children in Canada — from First Nations, Métis (Indigenous people in parts of Canada whose are of Indigenous and European ancestry) and Inuit communities — attended these schools, Indian Country Today reported. Until 1951, all Indigenous children ages 7 to 15 were required by law to attend a residential school, according to Indigenous Foundations. However, abuse continued as long as the schools were in operation, and students "received cruel and sometimes fatal treatment," representatives of the Lower Kootenay Band said in a June 30 statement.

"Horrendous abuse"

At the schools, children of all ages followed strict rules that restricted their use of Indigenous languages and forbade the practice of their traditions and customs. Breaking the rules meant harsh punishments, with former students describing "horrendous abuse at the hands of residential school staff: physical, sexual, emotional and psychological," according to Indigenous Foundations.

George Guerin, a former chief of the Musqueam Nation who attended the Kuper Island Residential School in British Columbia, recalled that one of the instructors, Sister Marie Baptiste, "had a supply of sticks as long and thick as pool cues. When she heard me speak my language, she’d lift up her hands and bring the stick down on me," according to Indigenous Foundations. From 2007 to 2015, Indigenous people who were former students at residential schools filed nearly 38,000 claims for injuries caused by physical and sexual abuse at the schools, according to the CBC.

For thousands of children, the schools' rampant abuse and neglect were deadly. The 2015 report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission documented 3,200 children who died while at residential schools, but the number of deaths could be 10 times higher than that, the CBC reported. Four years later, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation released the names of 2,800 of the children who could be identified; many of the children's families were never notified about their deaths, BBC News reported in 2019.

Beginning in the late 19th century, such residential schools were also established for Native Americans in the United States, according to the Library of Congress. Children at these schools were likewise separated from their families and traditions, and were subjected to harsh rules and often brutal treatment.

"Though we don’t know how many children were taken in total, by 1900 there were 20,000 children in Indian boarding schools, and by 1925 that number had more than tripled," according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), a nonprofit that formed in 2012 to increase public awareness about the U.S. Boarding School Policy of 1869. "The stated purpose of this policy was to 'Kill the Indian, Save the Man,'" NABS says. By the 1960s, the policy likely separated hundreds of thousands of Native American children from their families. Many children never returned from the schools, "and their fates have yet to be accounted for by the U.S. government," according to NABS.

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland recently announced the formation of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to review "the troubled legacy of federal boarding school policies," according to a June 22 statement issued by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Representatives of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation will release a detailed report of their Kamloops findings on July 15, Global News Canada reported, and the Canadian government has pledged $27 million to Indigenous communities for the identification of burial sites that are still hidden, according to the CBC.

"This was a crime against humanity, an assault on First Nations," Chief Bobby Cameron of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous First Nations in Saskatchewan, told NPR after the discovery of the graves at Marieval.

"We will not stop until we find all the bodies," Cameron said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.