Neanderthals 'Lived Fast, Died Young' Compared with Humans

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Kids may wish for shorter zit-filled childhoods and adolescence. But taking longer to mature may have given humans an evolutionary edge over Neanderthals by giving their brains and social skills more time to develop. Now dental records of early human fossils show how that developmental delay crept in over time.

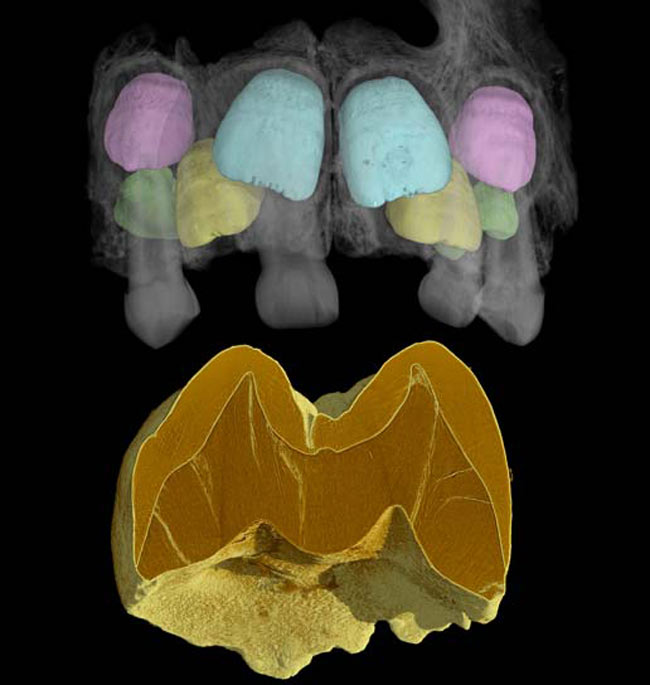

The average Neanderthal may have reached adulthood a few years before most modern humans, according to Tanya Smith, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University. She and her colleagues used synchrotron X-rays imaging to create a 3-D image of the teeth from 11 Neanderthals and early human fossils. (A synchrotron is a beam of X-rays as thin as a human hair and very intense such that it can reveal teensy details.)

"Teeth show biological rhythms – intrinsic or internal clocks that capture each day of their growth, as well as stress during development," Smith said. "Being born is stressful enough that this leaves a characteristic stress line we can identify – a birth certificate."

But she cautioned that the closely related human and Neanderthal populations make it difficult to pin down a precise difference in the actual ages of maturity. Other research has shown that modern humans still have Neanderthal genes from back when the two populations mated.

A prehistoric race in reverse

The Neanderthal tooth crowns grew significantly faster than modern human teeth. By contrast, the teeth of the juvenile Homo sapiens of the Middle Paleolithic era (200,000 to 45,000 years ago) matured at a rate that had greater resemblance to that of modern humans. (Neanderthals lived as far back as 230,000 years ago, disappearing from the fossil record a few thousand years after modern humans came onto the science, scientists have suggested.)

Those different rates of dental maturation seem consistent with other bodily markers of development among Neanderthals and H. sapiens. But compared with even earlier hominins, both Neanderthals and H. sapiens had longer periods of dental development.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Early humans also had longer pregnancies, childhoods, adolescence and life spans compared with non-human primates that exist today. Exactly when that evolutionary shift occurred since the split with non-human primates 6 million or 7 million years ago remains unclear.

Slow and steady does it

Still, it's the modern human slowpokes that may reap the greatest benefits of having more time before adulthood for their brains to learn complex social behaviors, Smith said. The current theories about development and cognition suggest that learning and neural organization continue well after final brain size is reached.

"The classic theory is that slowing down childhood may create favorable conditions for allowing this to happen more effectively in modern humans," Smith told LiveScience. "We don't have to deal with the pressures of obtaining social status or bearing offspring as early teenage chimpanzees do, for example."

Neanderthals were clearly evolving in the direction of the modern condition with longer development, Smith said. But it's the modern humans who represent a "unique extreme" in terms of having longer developmental periods.

Teeth in 3-D

The typical method for analyzing tooth lines representing stresses at certain ages would have required cutting up dozens of fossil teeth – something museum curators "would never allow," Smith said.

Instead, she and her colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Germany and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility used synchrotron X-ray imaging to create a 3-D view of the inner structures of the teeth.

"The synchrotron was critical for two main reasons – it is a 'virtual way' to see microscopic structure in 3-D – thus a really powerful way to visualize growth, and it is non-destructive – allowing us to look at some of the most famous Neanderthal and fossil Homo sapiens children in this study," Smith pointed out.

The study's specimens included the first hominin fossil, discovered in Belgium in the winter of 1829 to 1830. X-ray imaging revealed that the Neanderthal child was just 3 years old at the time of death, as opposed to previous estimates of 4 or 5 years old.

Now researchers will add this to the body of evidence as they try to understand the shift from a "live fast and die young" strategy to a "live slow and grow old" strategy.

- 10 Things That Make Humans Special

- Humans and Neanderthals Mated, Making You Part Caveman

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus