Giant Squid Filmed Alive for Second Time in History. Here's the Video.

For only the second time in history, researchers have recorded footage of a live — and very curious — giant squid in the pitch-dark depths of its salty, deep-sea home.

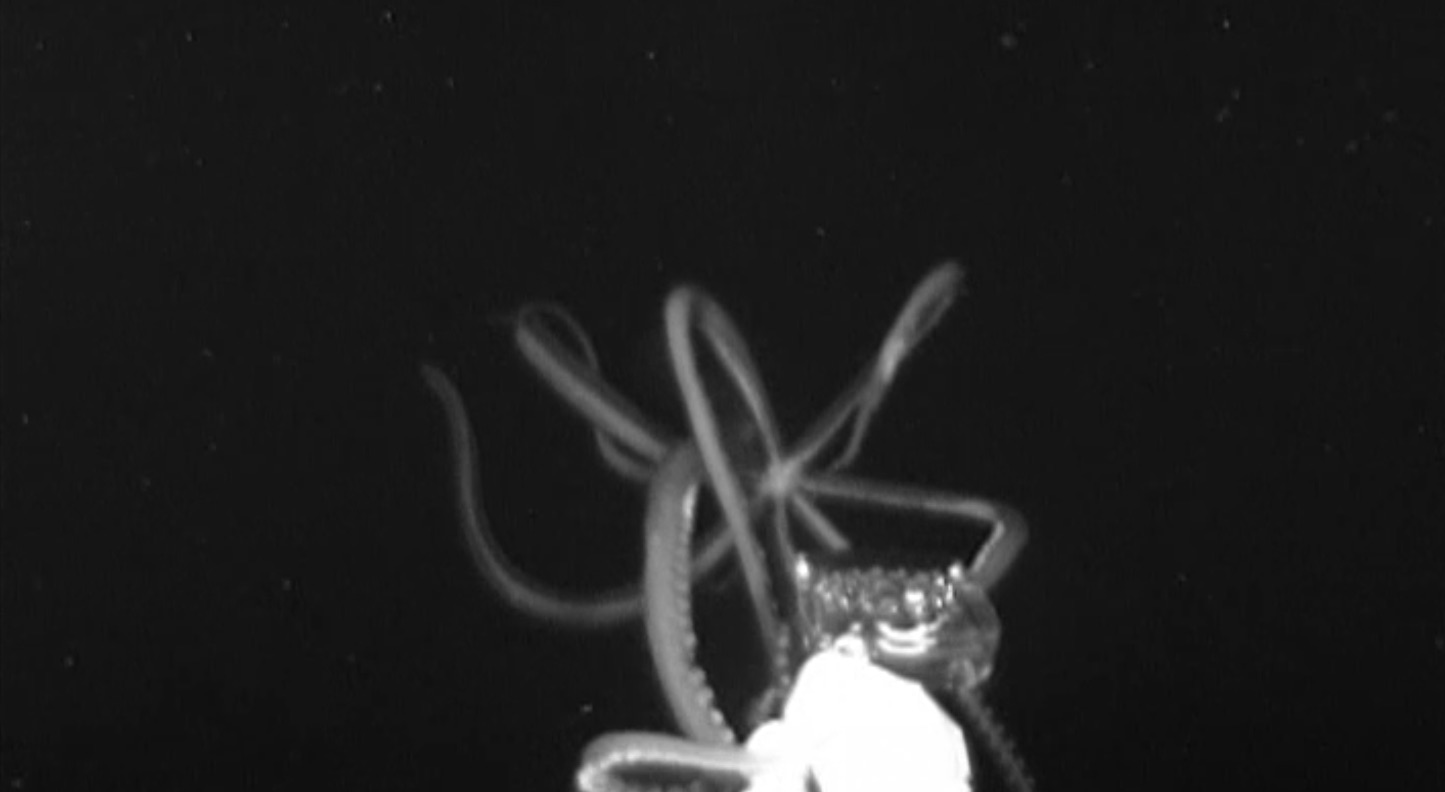

The short film, recorded in the Gulf of Mexico on June 18, shows the giant squid (Architeuthis) approach the faintly blinking lights on a decoy disguised to look like a bioluminescent jellyfish. (These giants are thought to eat smaller squid that feed on certain glowing jellyfish.) At first, the giant squid looks like a swimming slug until its eight legs unfurl, revealing its large suckers that it uses to inspect the device.

The moment the giant squid realizes that the lights aren't a jellyfish, it jets away. [Release the Kraken! Giant Squid Photos]

The fact that this giant squid was alive makes this encounter different from nearly every other time scientists have spotted these behemoths. Typically, the eight-legged creatures are not seen until they are found dead, trapped in deep-sea fishing trawls — the change in pressure and temperature when they are brought to the water's surface kills the animals — or mangled, washed up on shore.

"We're talking about an animal that can get to 14 meters [45 feet] in length," said Nathan Robinson, director of the Cape Eleuthera Institute, who was part of the team that recorded the video. "[The giant squid] has captured the imaginations of countless people, yet we have no idea what it's like, how it behaves or its distribution — where you find it. It remains this mystery. We know it's out there, we just know nothing about it."

Robinson credits the team, as well as the e-jelly with capturing the incredible footage. The e-jelly was developed by Edith Widder, CEO and senior scientist at the Ocean Research & Conservation Association (ORCA). When the deep-sea jellyfish Atolla wyvillei is threatened or attacked by a predator, it lights up like a burglar alarm. The e-jelly, which is part of the entire camera system called the Medusa, mimics this blinking light, with the aim of attracting giant squid.

Usually, when crewed, deep-sea submersibles or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) go underwater, they frighten away animals that live in the dim world of deep ocean. That's because these machines tend to be noisy, and shine bright lights on creatures that have never seen the light of day, Robinson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ORCA's contraption sidesteps these problems by sending down the Medusa, which is attached to the e-jelly. The Medusa can reach a depth of 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) underwater, where it records footage in ultra-low light with its highly sensitive camera and digital video recorder.

The Medusa and e-jelly combo helped Widder and her colleagues capture the first live footage of a giant squid in Japanese waters in 2012. This time, luck struck again ... and so did lightning.

Terrible weather

On June 19, one day after the footage was recorded, Robinson was reviewing the videos, which were taken deep underwater about 150 miles (240 km) off the Louisiana coast. Then, he saw the image of a weird tentacle stretch across the monitor. The rest of the research vessel's crew quickly gathered round the screen. They were fairly certain it was a giant squid — a juvenile at 10 to 12 feet (3 to 3.7 m) long — but they weren't 100% sure. [Gallery: Jaw-Dropping Images of Life Under the Sea]

Before the team could send the footage to a squid expert, lightning struck the ship.

"This all happened during a lightning storm," Robinson told Live Science. "As we were crowded round watching this footage, we heard a huge crack. We ran outside — there's a plume of black smoke bleeding out from the back of the boat because our antenna had literally exploded. And then we immediately ran back inside because we were like, 'Oh my, what if that just fried all of our computers?'"

One of the computers on board was fried, but thankfully, not Robinson's, which stored the giant squid footage. And if that wasn't enough excitement, about 30 minutes later, a water tornado, known as a water spout, threatened their ship.

Finally, the storm ended and their internet connection was restored. The team sent the footage to one of the world's leading squid experts, Michael Vecchione, an invertebrate zoologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., who confirmed that it was a giant squid.

The footage may be short, but every piece of knowledge scientists can learn about the giant squid — the animal with the largest eyes in the animal kingdom — rests on these rare recordings. The footage was captured just a few miles from the Appomattox deepwater oil rig, meaning that the giant squid's environment might be polluted, the researchers said.

"At present, we know so little about them that there's no way we can protect these animals," Robinson said. The more researchers learn, the better able they'll be to help protect the giants.The expedition, which was organized by Sönke Johnsen, a professor of biology at Duke University in North Carolina, was funded by the Office of Ocean Exploration and Research at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. You can read more about the adventure in a blog posted by Johnsen and Widder.

- Underwater Photos: Elusive Octopus Squid 'Smiles' for the Camera

- In Photos: Spooky Deep-Sea Creatures

- Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus