The Same Exact Foods Affect Each Person's Gut Bacteria Differently

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

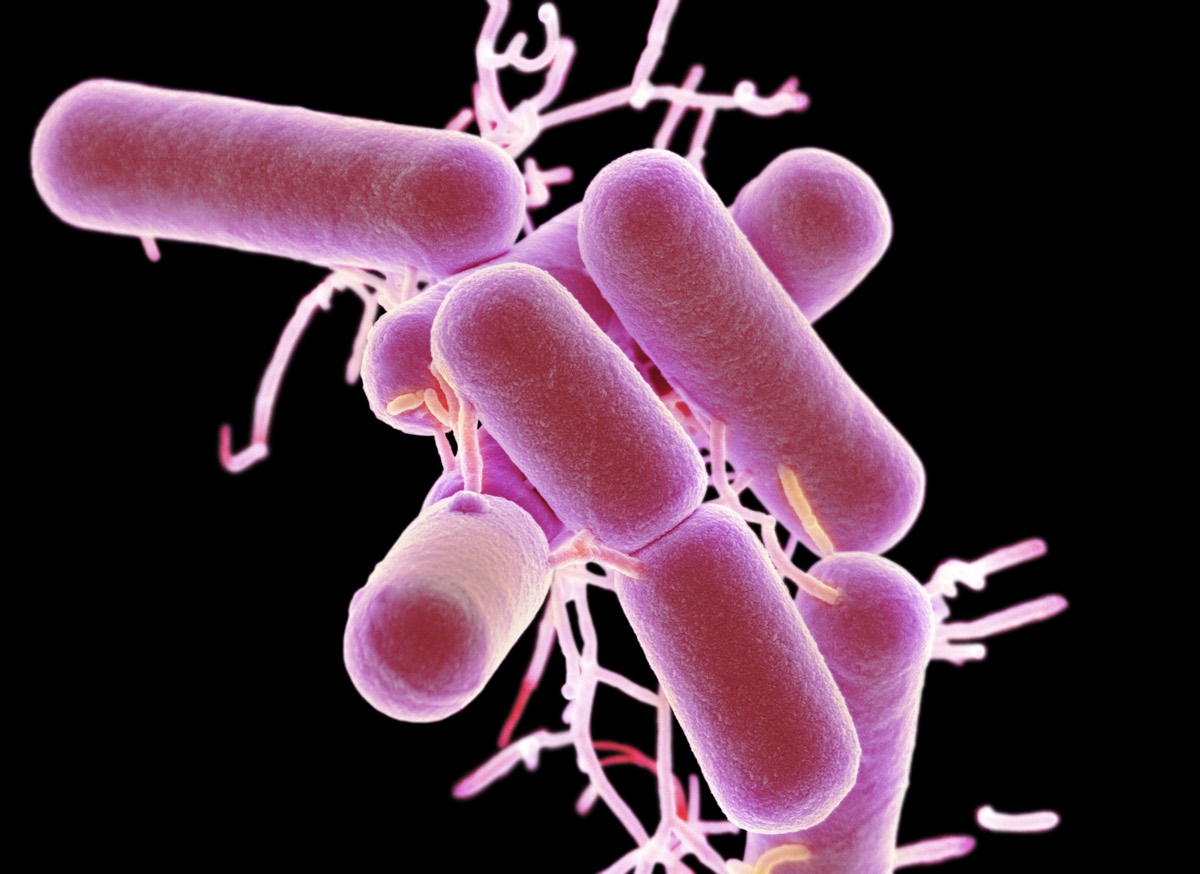

How does diet affect the thriving communities of microbes living in your digestive tract?

It's personal.

New research finds that the types of foods people eat really do impact the makeup of their gut microbiomes. However, the same food can have opposite effects in two different individuals. That means that the specifics of how diet will influence any given person's gut are still a mystery.

"A lot of the response of the microbiome to foods is going to be personalized, because each person has that unique mixture [of microbes] that's special only to them," said Dan Knights, a computational microbiologist at the University of Minnesota. [10 Ways to Promote Kids' Healthy Eating Habits]

Meals for microbes

The microbes that populate the intestinal tract may have a major influence on human health. Researchers have found that gut bacterial communities may be linked to the difficulty some people have losing weight, and they could play a role in cardiovascular disease. The microbiome also seems to be intimately tied to the immune system, and thus it plays an important role in immune-related diseases and disorders, including allergies.

A few studies have suggested that diet can influence the microbiome, Knights told Live Science, but the connection is poorly understood. He and his colleagues tackled the problem by asking 34 healthy volunteers to record every morsel of food and drink they consumed for 17 days straight. The participants then collected stool samples over the course of the study, which the researchers analyzed with a method called shotgun metagenomics. This method involves taking random samples of the genetic sequences in the microbes in the fecal material, Knights said, then piecing together what species and what genes those sequences came from.

This very detailed approach revealed that diet does indeed affect the gut bacteria. In a given person, the researchers could predict changes in the microbiome based on what they'd eaten in the days prior. For each person, they found a median of nine specific relationships between a type of food and specific gut microbiome changes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But those changes didn't generalize well from one person to the next. The team found 109 total food-gut microbe relationships that were shared by more than one research participant — but only eight that were shared by more than two. And of those eight, five of the relationships went in opposite directions. In one participant, eating a particular veggie caused a specific group of bacteria to multiply like mad. In another, that same veggie could quash that same group of bacteria.

What's in a food?

What's more, the nutrients on the nutrition label didn't correlate with any of these changes. At first, that seemed surprising, Knights said. But then, he said, "we realized it kind of makes sense, because the nutrition labels are written for humans."

And while humans might care about things like magnesium content and saturated fat, gut microbes are apparently a lot more interested in the unlisted stuff, including hundreds of unknown compounds that are in any given food. [11 Ways Processed Food Is Different from Real Food]

"There's all of this — I like to call it dark matter — that's in our foods that we're not really measuring," Knights said.

Instead, the correlations the researchers found were between gut microbes and specific food types, such as leafy green vegetables or yogurt (specific type notwithstanding). Two of the study participants consumed primarily meal replacement shakes of the Soylent brand. That turned out to be interesting, Knights said, because though those two people subsisted on the same thing almost every day, their gut communities changed daily, just as the microbiomes of those on a more varied diet did.

"There are very clearly other sources of variation in the microbiome in addition to the foods that we eat," Knights said.

The meaning of the microbiome

Despite the unique nature of each microbiome's response to specific foods, Knights believes there is a way to make sense of the data.

Doing so will require two approaches, he said. The first is to drill deep into what's actually in specific foods. Researchers will need to identify specific compounds that gut microbes metabolize, to understand the nitty-gritty details of the gut ecosystem.

"That's something that is going to take a lot of work, but we can get there," Knights said.

The second approach is to look at huge data sets on diets and microbiome communities, he said. With thousands of participants, trends can pop out, even if the details are unique to individuals, he said.

The study was funded by General Mills, the food manufacturer, reflecting that company's interest in basic nutrition research, Knights said. One major question he and his colleagues want to tackle is how the modern American diet affects the microbiome. People living in developing nations or in more traditional cultures have different gut microbiome communities from what's found in developed nations, Knights said.

"One thing we're very interested in understanding is how our diets in modern society might be contributing to the loss of our ancestral microbes," he said.

The researchers reported their findings June 12 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

- 5 Diets That Fight Diseases

- The Best Way to Lose Weight Safely

- 9 Meal Schedules: When to Eat to Lose Weight

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus