Why Do Skulls Have So Many Bones? (It's Loads More Than You Think)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

How many bones are in your skull? You might guess that animal skulls are made up of two bones: the upper region of the skull and the lower jaw. But skulls are actually far more complex — and have a lot more bones — than you may expect.

Some animals have more individual bones in their skulls when they're young and growing, though these later fuse together. However, some animals retain dozens of skull bones through adulthood.

Why are there so many bones in animal skulls, and which animals have the most? [What Is the Toothiest Animal on Earth?]

Human skulls have 22 bones: 8 cranial bones and 14 facial bones, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The forehead bone — a single bone called the frontal — is actually two separate bones in newborns that fuse as the baby grows.

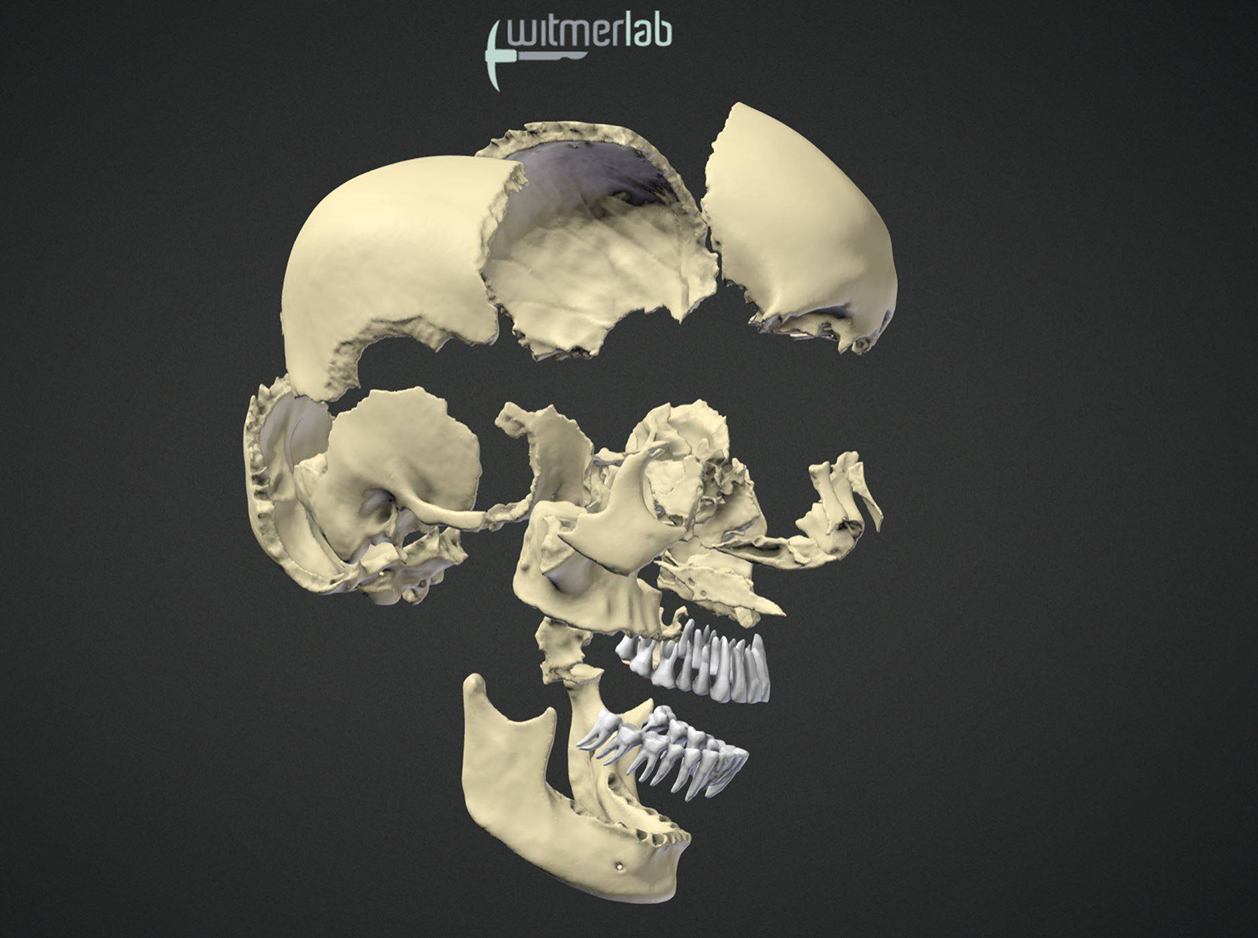

By comparison, alligator skulls have around 53 bones. Researchers at the Witmer Lab at Ohio University recently demonstrated that astounding number with a photo of a disarticulated alligator skull that they shared on Twitter.

Mammal fetuses have approximately 43 bones that are developmentally distinct, "but some of them fuse as mammals grow," and the number of fused bones may differ among mammal groups, Jack Tseng, a functional anatomist at the University at Buffalo, told Live Science in an email.

"I would say that you could probably find marsupial species with close to that number of skull bones," Tseng said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The greatest number of skull bones by far — 156 — occurs in the fossil of an extinct fish, said Brian Sidlauskas, an associate professor and Curator of Fishes with the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife at Oregon State University.

"Fishes vary in the number of bones in their heads," Sidlauskas told Live Science in an email. "Typically numbers are probably in the range of 130 or so," he said.

The number of bones in vertebrates' skulls, how they fit together and where they fuse to each other varies widely, and can reflect how the skull is used by the animal and how much flexibility it requires, said Larry Witmer, a professor of anatomy and paleontology with the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Ohio University.

Fish, for instance, have highly mobile skulls; that mobility is possible because they have more skull bones and fewer fusions than most other vertebrates, Witmer told Live Science. Some types of fish even have a second set of jaws called pharyngeal jaws, which extend from inside the external jaws — just like those in the horrifying xenomorph in the "Alien" movies, according to Witmer.

"To maintain that movement within the skull, something we call cranial kinesis, you need a whole bunch of bones," Witmer said. "You need to maintain these mechanical linkages that allow muscles to move parts of the skull relative to other parts."

In addition to the skull bones that fish share with other animals, they also have opercular bones — four fused bones that cover their gills. Some amphibians retain these bones as well, though they are much smaller than the opercular bones in fishes, but all other vertebrates lack these skull bones, said Paolo Viscardi, curator of zoology at Ireland's Natural History Museum.

"The skull itself is more variable in fish than other vertebrates — unsurprising when you consider that all other vertebrates are derived from a single lineage of fish, so there would have been a bottleneck in cranial diversity at that point," Viscardi told Live Science in an email.

"This means that other vertebrates have a fairly conservative skull morphology, with most having 22 bones," he said. And unlike terrestrial vertebrates, fish don't have to deal with gravity constantly dragging at their skulls, so the bones overall tend to be lighter and more flexible than skull bones in animals that live on land, Viscardi explained.

Regarding birds, many of which also have highly flexible skulls, heightened mobility came from losing some bones that their dinosaur ancestors once had, according to Witmer. Birds tend to have a lot of individual skull bones as hatchlings, but many of them fuse together by the time they reach adulthood. However, they retain more than a dozen individual bones in their bony eye rings, or scleral rings.

"A lot of birds tend to have 14 or 15 of these bones in each eye, so that winds up being 30 bones right there," Witmer said. Lizards and some fish also have these scleral rings, but it's unclear what function they serve, he added.

As animals evolved over millions of years, some skull bones became bigger, some became smaller, some fused and some were lost entirely; "this variation and flux in the numbers of bones among different groups is a fascinating thing that speaks to the rich fabric of evolution," Witmer said.

- Why Are Teeth Not Considered Bones?

- In Photos: Ancient Fish Skull From Siberia

- Get Stuffed: Which Animals Challenge Taxidermists the Most?

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus