How Much Do Babies’ Skulls Get Squished During Birth? A Whole Lot, 3D Images Reveal

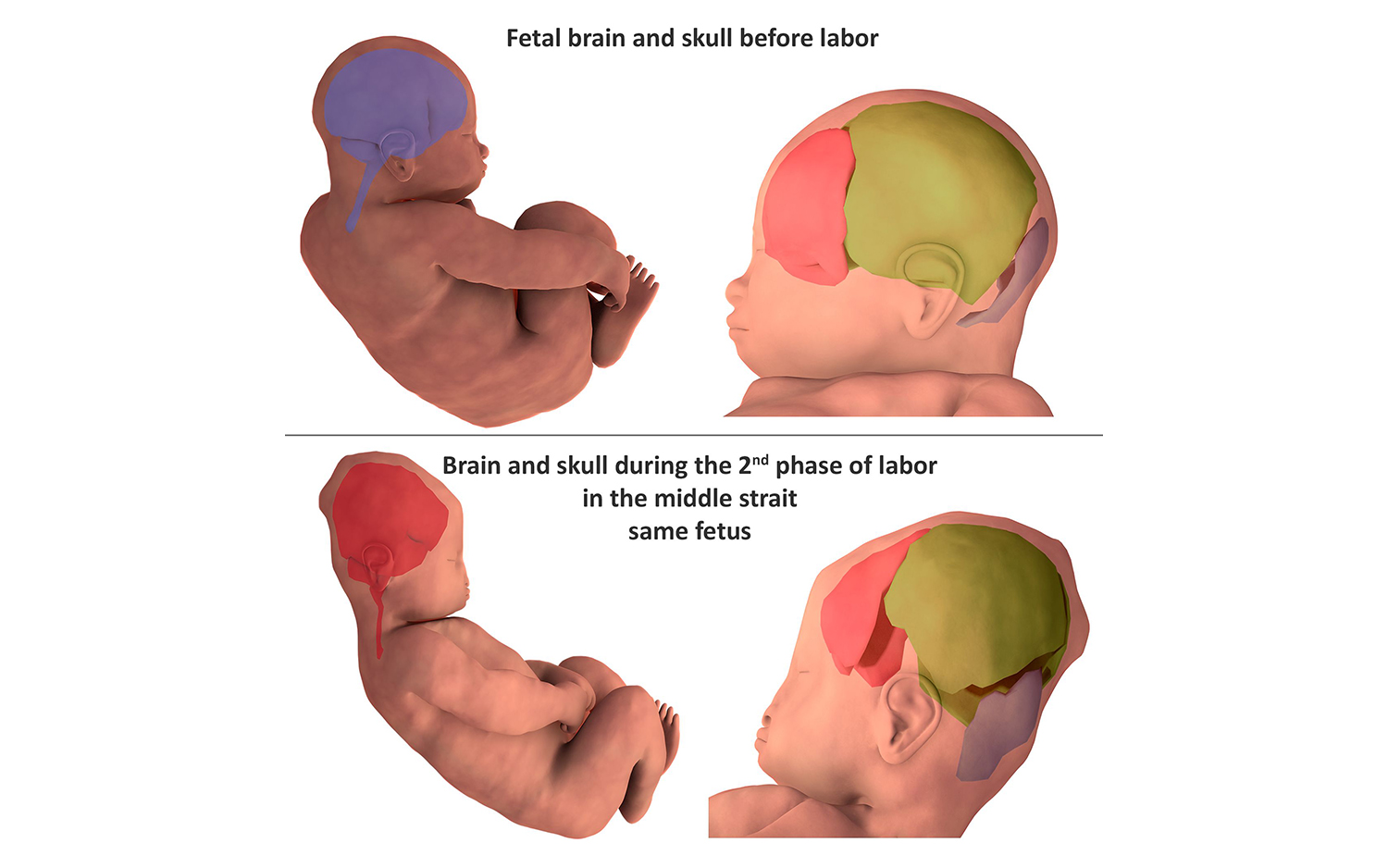

When babies pass through the mother's birth canal, the tight fit temporarily squashes their wee heads, elongating their flexible skulls and changing the shape of their brains. Now, scientists have created 3D images that demonstrate the extent of that amazing conehead-like distortion.

Babies' heads can change shape under pressure because the bones in their skulls haven't fused together yet, according to the Mayo Clinic. Soft regions at the top of the head accommodate being squeezed through the birth canal and allow room for the brain to grow during infancy.

However, the precise mechanics of how a baby's skull and brain change shape during labor are not well understood. To learn more about that process, scientists conducted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of seven pregnant women: when the subjects were between weeks 36 and 39 of their pregnancies, and then when they were undergoing labor, after their cervixes were fully dilated. [7 Baby Myths Debunked]

Their images revealed significant skull squeezing — known as fetal head molding — in all the infants, and suggested that the pressures exerted on infant heads and brains during birth are stronger than once thought, scientists reported in a new study.

In all seven fetuses, skull bones that did not overlap prior to labor were visibly overlapped once labor began, deforming the infants' heads and brains, the researchers wrote. In five babies, the skulls returned to their prelabor shapes soon after birth, and the deformation was not noticeable when the newborns were examined.

The MRI scans captured views of soft tissues that were not visible with ultrasound, providing important clues for understanding the deformation of fetal skulls and brains, and the movement of maternal soft tissues around them during birth, according to the study.

The findings were published online today (May 15) in the journal PLOS One.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- 11 Big Fat Pregnancy Myths

- Wonder Woman: 10 Interesting Facts About the Female Body

- Trying to Conceive: 10 Tips for Women

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus