How the US Veered Off the Path to Measles Elimination

Nearly two decades ago, measles was eliminated from the U.S.

But the highly contagious disease is back, due in part to anti-vaccine ideologies. Since January,there have been more than 760 cases of measles in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

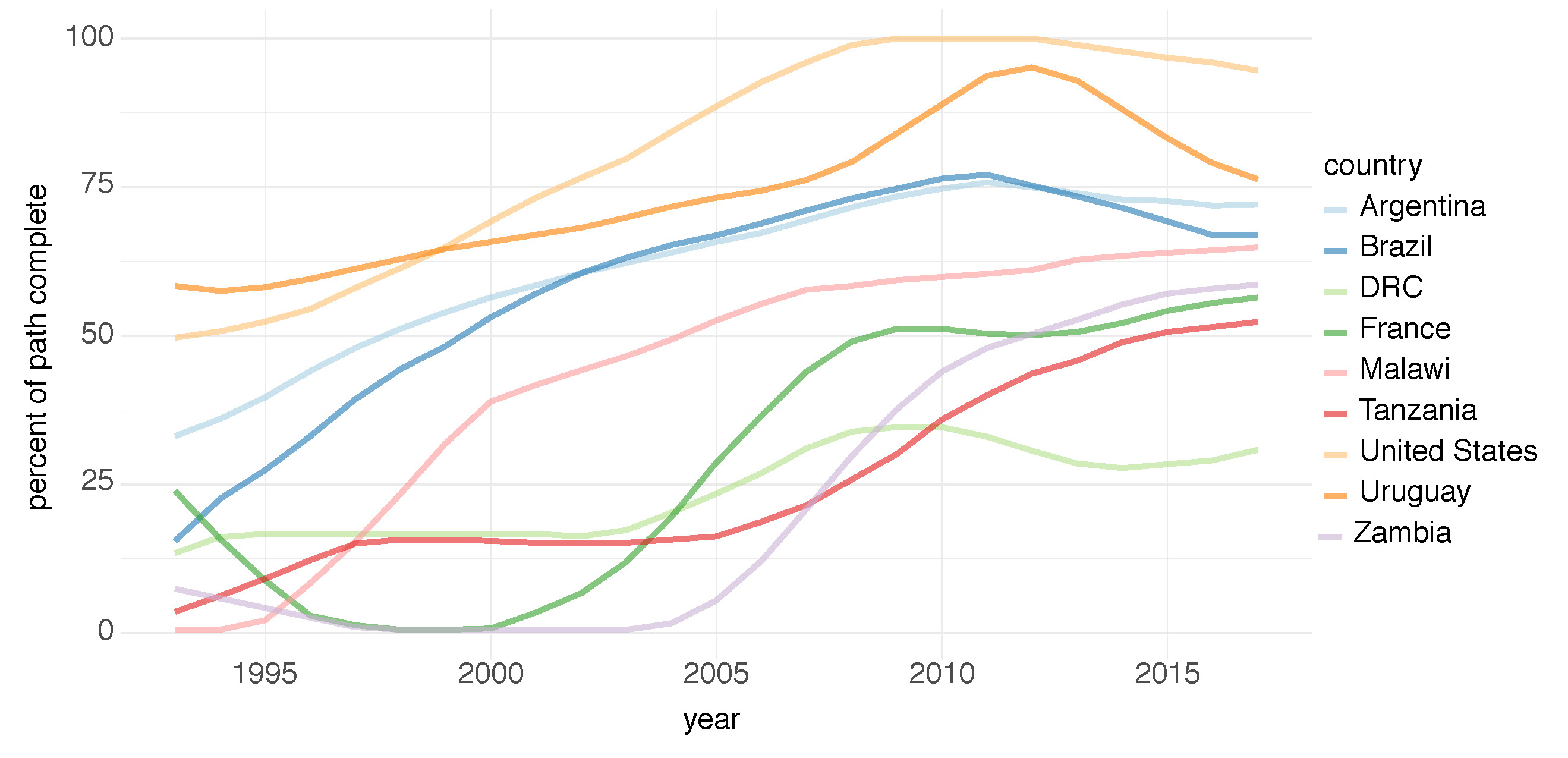

Now, the country, once having crossed the "finish line" on the typical path to measles elimination, is moving backward, according to a new study published today (May 9) in the journal Science.

In the study, researchers analyzed three decades of global data from the World Health Organization (WHO) on measles cases and vaccination rates. They found that countries tend to follow a very predictable path as they work toward eliminating the disease. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The path to elimination begins with high rates of measles infections, which then sharply decline as vaccination rates increase, the study found. As the infection rates drop, however, variability in measles outbreaks increases. This means that it becomes harder to predict when an outbreak will occur; some years, a specific area will be measles-free, and other years, there might be outbreaks. Finally, outbreaks decrease in frequency, and measles cases occur at consistently low rates, until the disease is eliminated.

What's more, the researchers found that, as countries move along this typical path, the groups of people who were infected changed: At the beginning of the path, measles rates were higher in younger people. But as countries moved along the path and successful vaccination programs began protecting children, measles rates became relatively higher in older people.

Successful vaccination programs reduce the number of people susceptible to measles overall, but the people who remain susceptible to the virus get older, said co-lead study author Amy Winter, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Countries are on different parts of the path to elimination. For example, some countries in Africa and Asia are farther behind, with measles cases numbering in the tens of thousands since 2018, Winter told Live Science. However, those cases end up being more predictable, she said.

Still, the researchers noted that countries can veer off the path, in both positive and negative ways.

"Countries may deviate from this path for good reasons — for instance, having very strong elimination programs that allow them to short-circuit that period of high variability and go directly to elimination," senior study author Justin Lessler, an associate professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins, said in a video statement. But countries can also deviate for "bad reasons, because their programs are failing, and they'll move backwards across the path as we might be seeing in some parts of the Americas."

Though the U.S. is indeed moving backward on the path, the country is still farther along than many other countries. But because of the backslide, "we can [now] expect that there's going to be dramatic increases in year-to-year variability," Winter said.

The WHO has a goal of eliminating measles from all six of its regions — which include all of the world except Antarctica — by 2020. The only region that had achieved a total elimination of measles was the Americas.

- 10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors

- 13 Animal-to-Human Diseases Kill 2.2 Million People Each Year

- Germs on the Big Screen: 11 Infectious Movies

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus