This Tiny Knee Bone Had Nearly Vanished As Humans Evolved. It's Coming Back

A tiny bone hidden in the tendon of the knee started to disappear over the course of human evolution ... or so scientists thought.

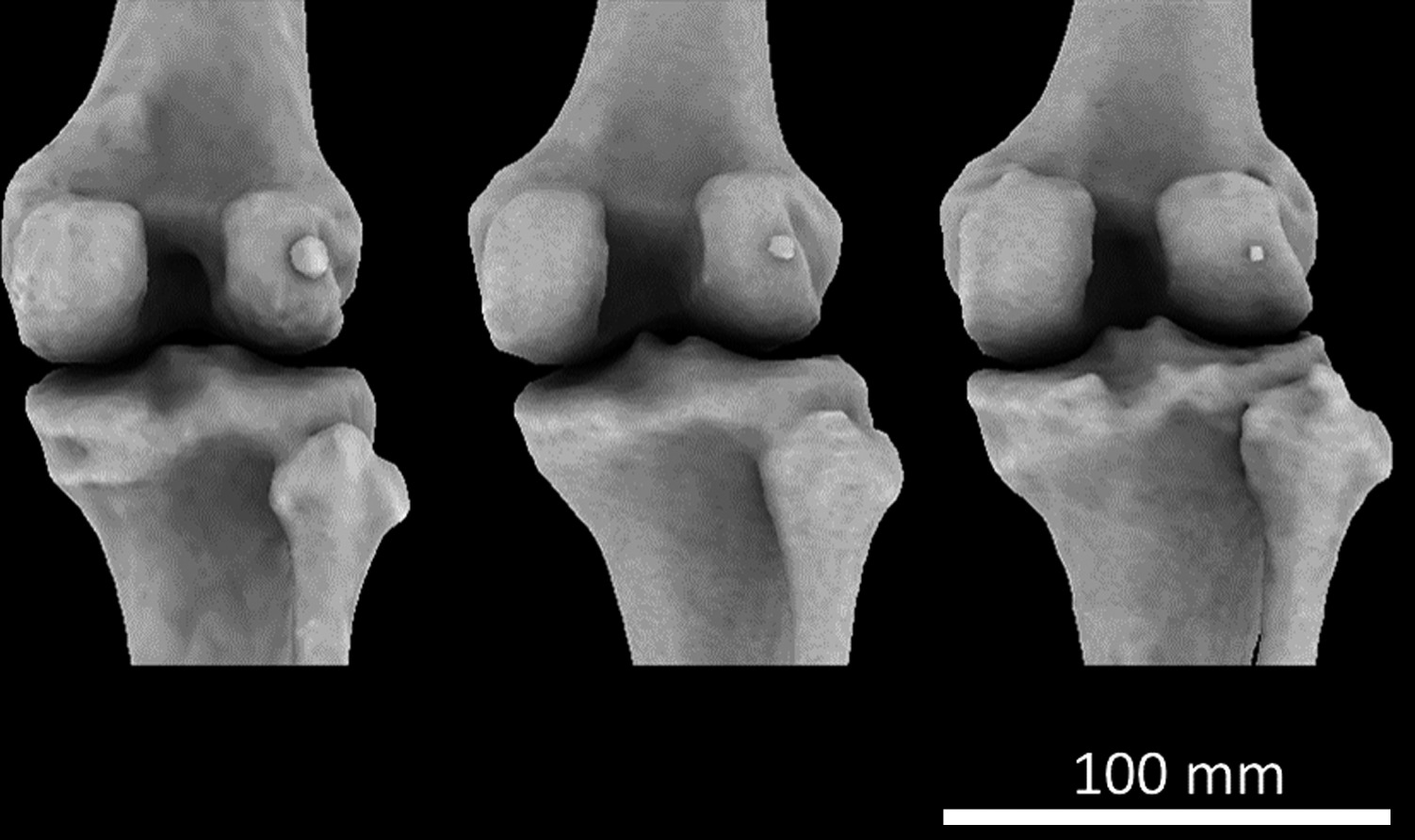

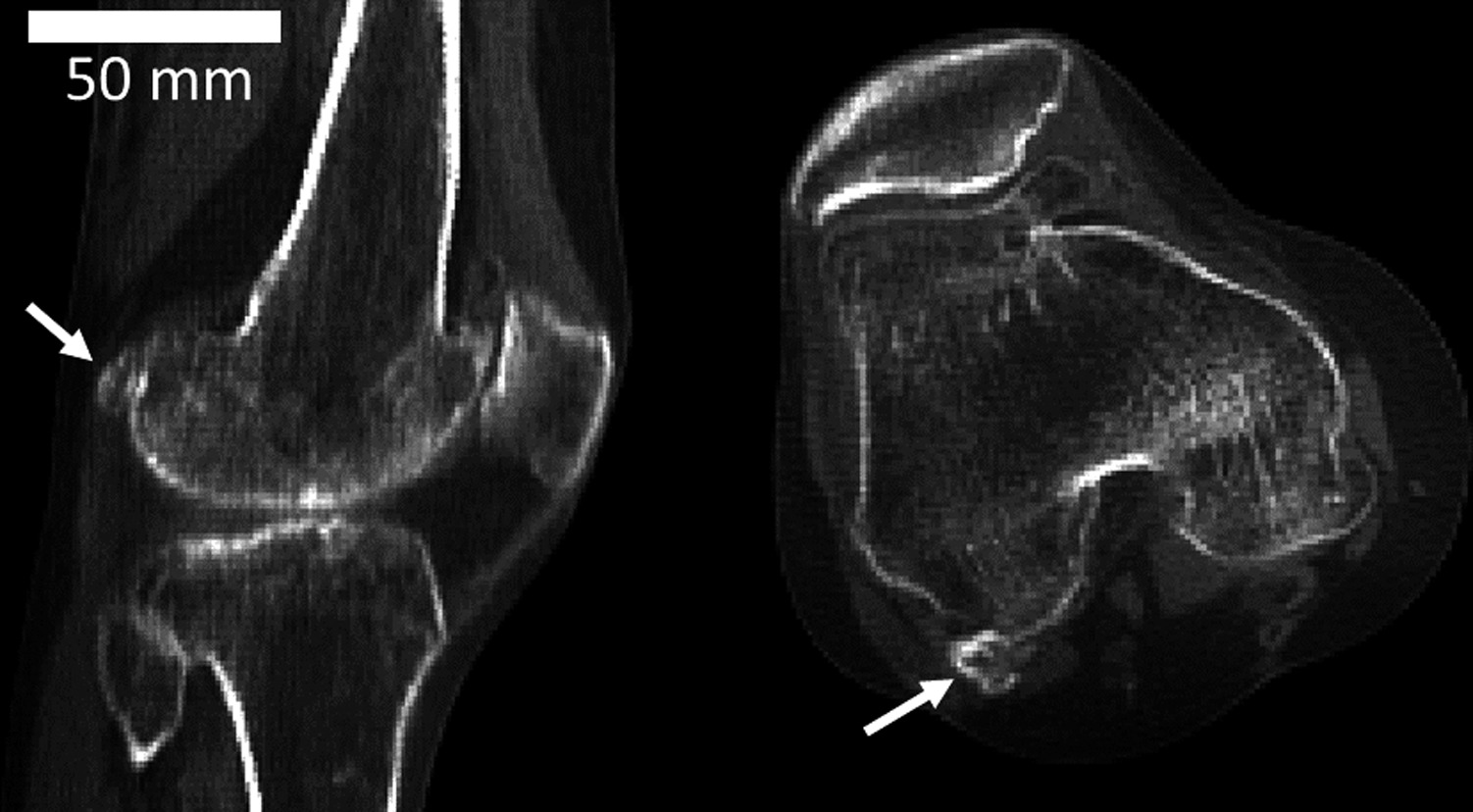

Now, a new study finds that this so-called fabella (Latin for "little bean") is making a comeback. The bone, which is a sesamoid bone, or one that's embedded in tendons, is three times more common in humans now than it was a century ago, scientists reported Wednesday (April 17) in the Journal of Anatomy.

A group of Imperial College London researchers reviewed records — such as results from X-rays, MRI scanning and dissections — from over 27 countries and over 21,000 knees. They combined their data to create a statistical model estimating the prevalence of this elusive bone across time.

In the earliest records that dated back to 1875, they found that the fabella was found in 17.9 percent of the population. In 1918, it was present in 11.2 percent of people, and by 2018, it hid within the tendons of 39 percent of the population. [The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body]

The bone has been previously linked to arthritis or joint inflammation, pain and other knee problems, according to a statement from the Imperial College London. Indeed, people with osteoarthritis of the knee are twice as likely to have this bone than in people without, they wrote.

Long ago, the fabella served a purpose similar to that of a knee cap for Old World monkeys, according to the statement. "As we evolved into great apes and humans, we appear to have lost the need for the fabella," lead author Michael Berthaume, an anthroengineer at the Imperial College London, said in the statement. "Now, it just causes us problems — but the interesting question is why it's making such a comeback."

Sesamoid bones like the fabella are known to grow in response to mechanical forces, according to the statement. Because humans are now more nourished than their ancestors were, making them taller and heavier, the body puts more pressure on the knee, Berthaume said. "This could explain why fabellae are more common now than they once were."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- 7 Weird Facts About Balance

- 11 Surprising Facts About the Immune System

- Ready for Med School? Test Your Body Smarts

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.