Thousands of Writhing Maggots Create the World's Creepiest Fountain

Now, picture that fountain made of thousands of wriggling fly larvae.

That's what scientists found while studying the dinnertime of black soldier fly larvae, or maggots. When vast quantities of these larvae feed together, their surging movement around their food creates a living fountain of writhing bodies. That may sound revolting, but the strategy makes maggots uniquely efficient at devouring meals en masse, scientists reported in a new study. [Ear Maggots and Brain Amoeba: 5 Creepy Flesh-Eating Critters]

Larvae of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) typically hatch, live and eat together in the hundreds and thousands, and each voracious grub can consume up to twice its body mass in a day, lead study author Olga Shishkov, a doctoral candidate in mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech, told Live Science.

Other animals, such as piranhas and flesh-eating dermestid beetles, are also known to feed quickly in large groups, and these carnivores can swiftly reduce a corpse to a stripped skeleton. But the dynamics of group-feeding behavior are not well-understood, so the researchers decided to dive deep into piles of maggots (figuratively speaking) to see what the energetic larvae might reveal.

"If you watch a video of any kind of maggots, they squirm around a lot. They're constantly in motion," Shishkov said. "If this didn't benefit them, they probably wouldn't be wasting their energy."

Go with the flow

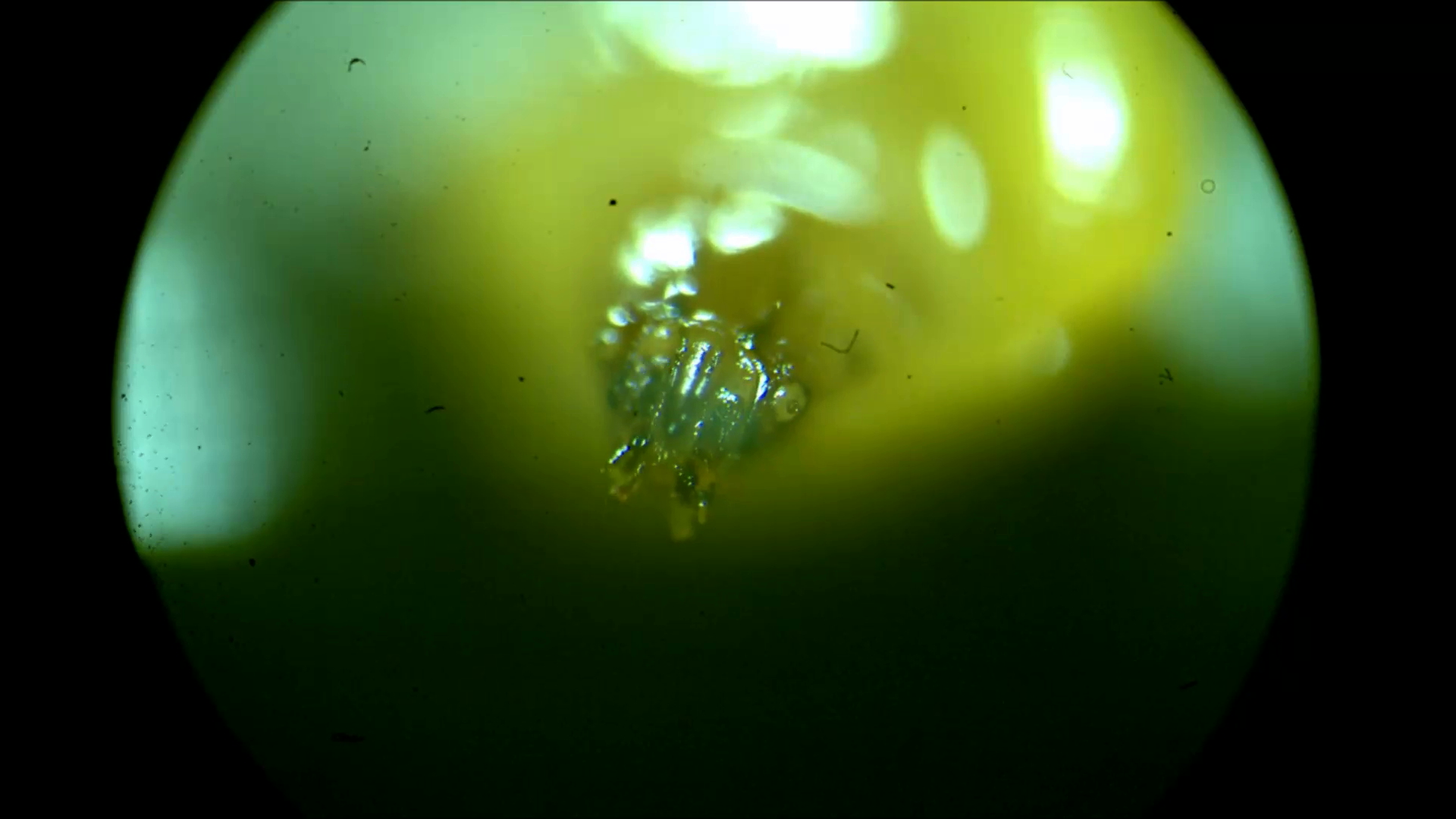

Using cameras positioned above and below fish tanks, the scientists filmed feeding sessions of groups of larvae — from 500 to 10,000 individuals — as the maggots swarmed around orange slices. The researchers then used a technique called particle image velocimetry (PIV) to analyze the flow and movement of the group as a whole.

As the larvae fed, their movements seemed random to the naked eye, but algorithms detected "a coherent flow direction," the study reported. Viewed from the top, particle analysis showed the mass of maggot bodies flowing outward. Meanwhile, the view from the bottom revealed a flow inward, along with a vortex of the entire feeding mass.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What was happening? When the larvae swarmed around their food, wriggling maggots at the bottom closed in for the first bites. But as the diners' eager neighbors squirmed around them, the first eaters were carried upward by waves of other hungry maggots. Once they reached the top, they tumbled all the way down — an effect resembling water flow in a fountain, the study authors said.

"New larvae crawl in from the bottom and are 'pumped' out of the top," the authors wrote.

Larvae typically eat for only 5 minutes at a time; a flowing momentum in the group means that larvae that are close to the food and resting get moved aside to make room for maggots with empty bellies. This "fountain of larvae" feeding strategy is unique to maggots, because it involves a level of prolonged, full-body contact that is simply not feasible for other types of animals, the scientists explained in the study.

The findings were published online Feb. 6 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

- Coffee to Maggots: Top 10 Bad Things That Are Good for You

- Bugs for Everyone! Awesome Insect Photos Shared in Free Project

- No Creepy Crawlies Here: Gallery of the Cutest Bugs

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus