Earth's Magnetic North Pole Was Moving So Fast, Geophysicists Had to Update the Map

Now that the government shutdown is over, federal agencies have finally released an early edition of the World Magnetic Model, almost a full year before the next one was scheduled to be released, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced today (Feb. 4).

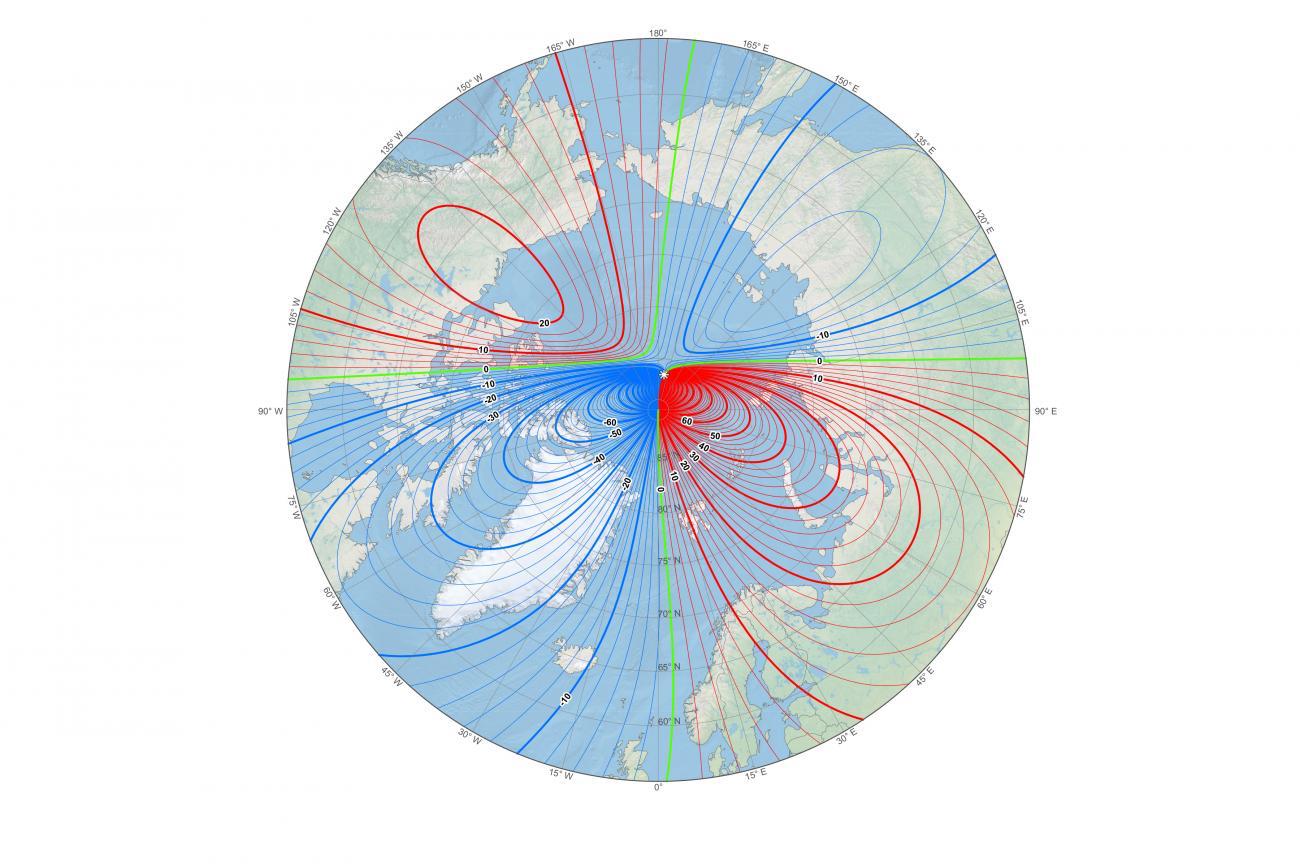

Previously, the World Magnetic Model, which tracks Earth's roving magnetic north pole, was updated in 2015 with the intent that the model would last until 2020. But the magnetic north pole had other plans. It began lurching unexpectedly away from the Canadian Arctic and toward Siberia more quickly than expected.

"We regularly assess the quality and accuracy of the model by comparing it with more recent data," said Arnaud Chulliat, a geophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder and NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). In January 2018, "we figured out that the error was increasing relatively fast, especially in the Arctic region. And the error was on track to exceed the specification before the end of the five-year interval." [Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit]

Almost immediately, NOAA scientists began to work with their counterparts at the British Geological Survey in Edinburgh, Scotland, to produce an update. The scientists collected the most recent data of magnetic field recordings from the past few years and plugged that into the model, which allowed the researchers to extrapolate where the pole would be in the near future, Chulliat said.

The updated model was initially slated to be released on Jan. 15, but the release was delayed because of the 35-day government shutdown, which lasted from Dec. 22, 2018, until Jan. 25, 2019.

However, this update will be used only for 2019. At the end of this year, the new World Magnetic Model for 2020 through 2025 will be released, Chulliat told Live Science.

Despite its short-term use, this unexpected update is vital to navigators the world over, including those in charge of military, undersea and aircraft navigation; commercial airlines; search-and-rescue operations and other projects circling the North Pole, NCEI reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other agencies, such as NASA, the Federal Aviation Administration and the U.S. Forest Service also rely on the model for surveying and mapping, satellite and antenna tracking, and air-traffic management. Even smartphone and consumer electronics companies need an accurate model so that they can provide users with up-to-date maps, compass applications and GPS services.

Researchers have known since the 1800s that magnetic north isn't static. But in the 1990s, it started moving faster, from just over 9 miles (15 kilometers) a year to about 34 miles (55 km) annually, Chulliat said. Then, in 2018, it took a leap over the international date line and took up residence in the Eastern Hemisphere.

Interestingly, magnetic north has been moving closer to true north over the past few years. "It's coming from a place where it was farther away from the north geographic pole, and now it's very close to the geographic pole," Chulliat said. "But, of course, if it continues in the same direction, it will go past the geographic pole and farther away again, but on the other side of the Earth, on the Russian side."

Unpredictable flows in the Earth's core are responsible for magnetic north's unusual behavior, the NCEI said. Scientists are still trying to understand the movement, but one idea is that a high-speed jet of liquid iron under Canada is being smeared out and essentially weakened over time, Phil Livermore, a geomagnetist at the University of Leeds in England, told Nature in January.

"The location of the north magnetic pole appears to be governed by two large-scale patches of magnetic field, one beneath Canada and one beneath Siberia," Livermore told Nature. "The Siberian patch is winning the competition."

- Photos: The World's Weirdest Geological Formations

- In Photos: The UK's Geologic Wonders

- Aurora Photos: See Breathtaking Views of the Northern Lights

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus