Secret Soviet Bunkers in Poland Hid Nuclear Weapons

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In the 1960s, the Soviet Union built massive bunkers in Poland. These bunkers didn't appear on maps, and were carefully concealed to be invisible to spies from the air.

But now, these long-abandoned buildings are revealing some of the secrets of Russian military strategy during the Cold War.

Soviet documents from that time period described the sites as communications centers, though the buildings vanished from official records soon after they were built. Indeed, at the time, the Soviet Union denied having nuclear weapons cached anywhere in Poland.

But researchers are finally taking up the investigation of these secret sites, and uncovered the bunkers' primary purpose: storehouses for nuclear weapons. [In Photos: Soviets Hid Nuclear Bunkers in Poland's Forests]

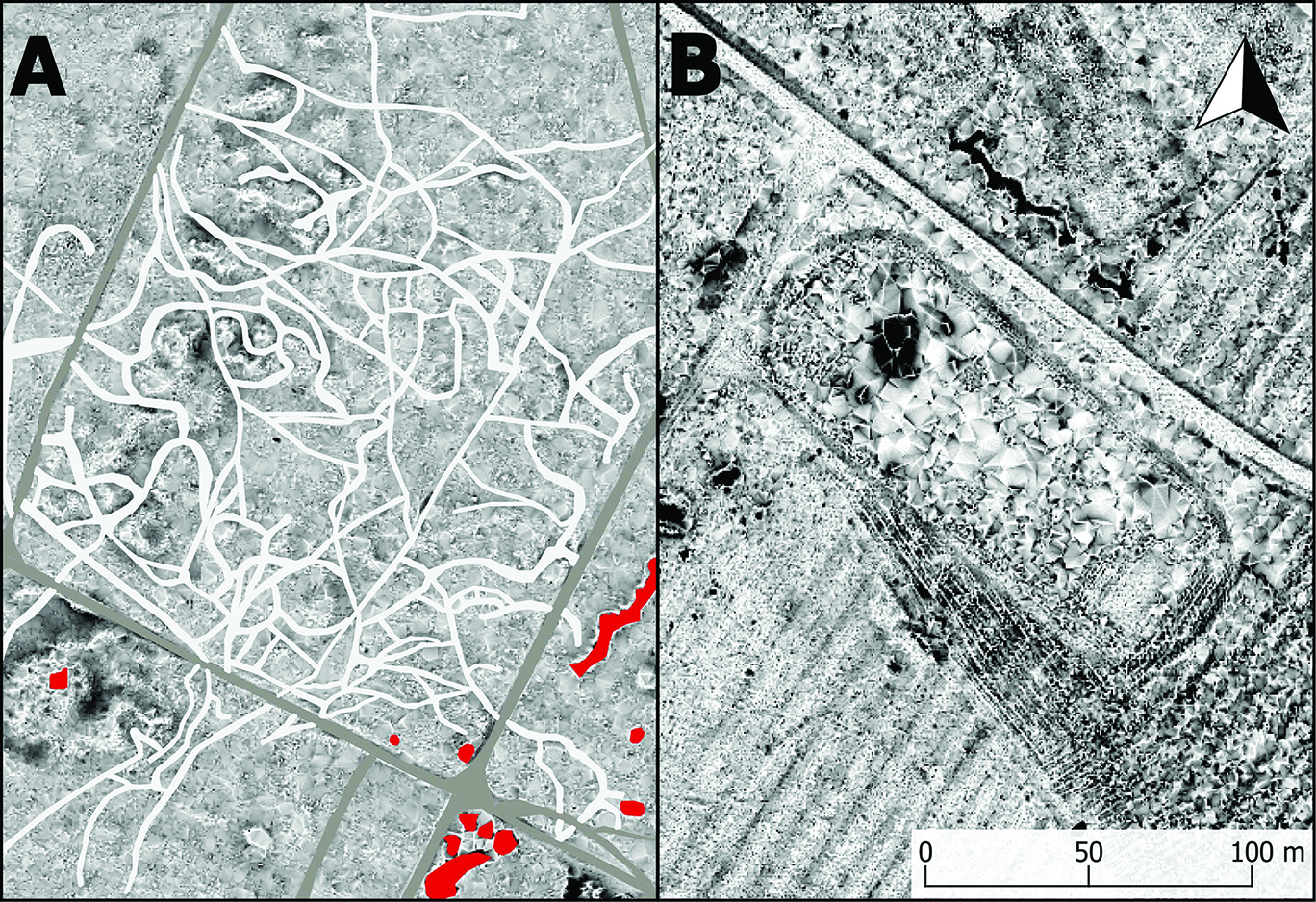

Archaeologist Grzegorz Kiarszys, an adjunct professor at the Institute of History and International Relations in Poland, has conducted the first in-depth exploration of three of these nuclear warhead storage facilities. By delving into archives of declassified satellite images and analyzing building scans, Kiarszys is piecing together the role that these secret sites played on the global chessboard, at a time when the threat of nuclear war between the world's biggest superpowers was all too real.

His findings were published online today (Jan. 21) in First View, a preview of the journal Antiquity's February 2019 issue.

Tactical storage

For the study, Kiarszys looked at three abandoned top-secret facilities that stored nuclear weapons and housed military personnel: one near the town of Podborsko, another near Brzezń ica Kolonia, and the last near Templewo. All were built in the late 1960s and their bunkers were similar to ones that the Soviets used during that period to house nuclear weapons in East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nuclear missiles stored at the sites were likely tactical warheads intended for launching at parts of Europe, in case of a future war, Kiarszys told Live Science.

"The power of warheads varied from about 0.5 to 500 kilotons. Those warheads were to be used in the so-called Northern Front, for invasion of the northern part of western Germany and Denmark," he said. Should a situation demand the warheads' deployment, they would be loaded on trucks, brought to nearby airfield and then mounted on rockets, Kiarszys explained.

Poland financed and built the three bunkers according to plans provided by the Soviets, completing the work in December 1969 and turning control of the buildings over to Russian troops, Kiarszys said.

"After that, only Russian troops had access to those facilities," he said.

Because the plans and maps were destroyed and the sites were scrubbed from official records Kiarszys relied on declassified CIA satellite imagery and modern remote-sensing techniques to glean clues about the facilities' organization and protection, and how that changed over time.

Secret sites revealed

Remote sensing and satellite surveillance photos revealed that there was a similar number of buildings at all three sites, with "a large number of field fortifications, trenches, car shelters, checkpoints, observation points, strong points all around the bases," he said. Each base had three main zones, the most important being a restricted area that likely housed nuclear warhead storage bunkers. Each site also had a garage area and a barracks zone with housing, bathing facilities, mess halls, and other necessities for daily life, Kiarszys said.

Additional tests for the study were conducted inside the bunkers by nuclear physicists, checking for signs of radiation. However, no contamination was detected, perhaps because of the Soviets' high safety standards for warhead storage, Kiarszys said.

But it's also possible that the storage chambers were never used for their intended purpose, and nuclear weapons were never contained there at all, he added.

Kiarszys also created detailed maps of the deserted building complexes, which likely housed young soldiers completing their training, non-commissioned officers, and officers with their families. [Gallery: Declassified US Spy Satellite Photos & Designs]

Decades of neglect and vandalism have already damaged many of the structures at these sites, and these findings underscore the importance of preserving and protecting these and other remnants of the Cold War, Kiarszys said. As relics of an era when people lived under the constant threat of nuclear war, they serve as a sobering reminder to safeguard against the danger that nuclear weapons still pose today, Kiarszys said.

- Photos: Top-Secret, Cold War-Era Military Base in Greenland

- Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets

- Declassified! 1972 Spy Satellite Capsule's Deep-Sea Rescue (Photos)

Editor's note: This story was updated Jan. 22 to clarify that nuclear warheads were transported to airfields for deployment, and were not launched from storage sites.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus