Extreme Microbes Found in Crystals Buried 200 Feet Beneath the Sea of Japan

Scientists discovered the crystal-encased microbes during an expedition to Joetsu Basin to sample gas hydrates — crystalline solids of gas and water that form in the ocean under high pressure and intense cold. They presented their findings in December at the annual conference of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

After the researchers examined massive hydrates collected at the sea bottom off Japan's western coast, they found that some of the hydrates contained tiny grains of a mineral called dolomite. And dark spots in the dolomite hinted that there was yet another surprise to come, researcher Glen Snyder, a professor at Meiji University in Japan, told Live Science at the conference. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

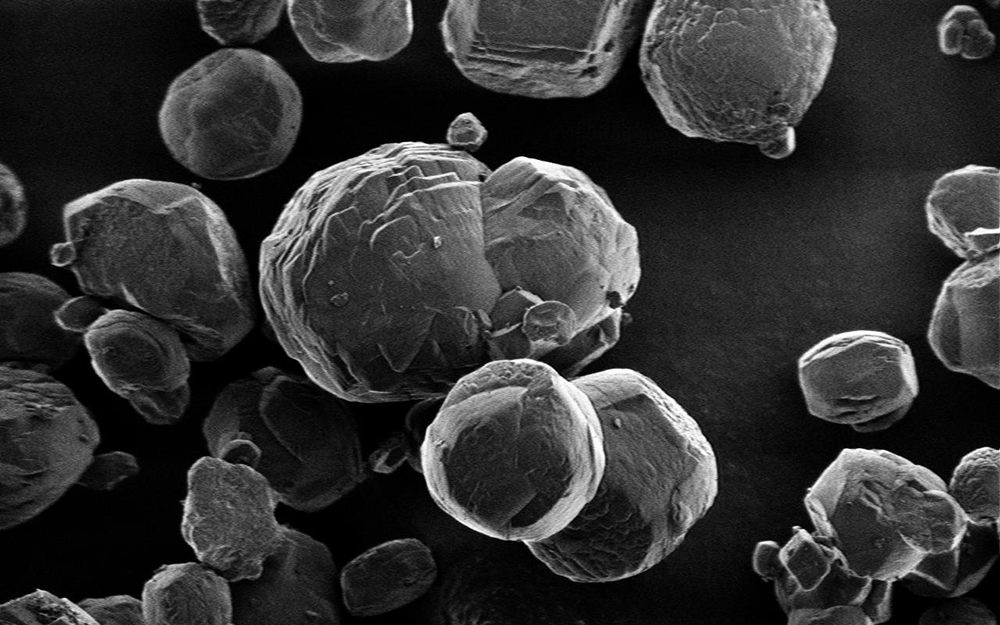

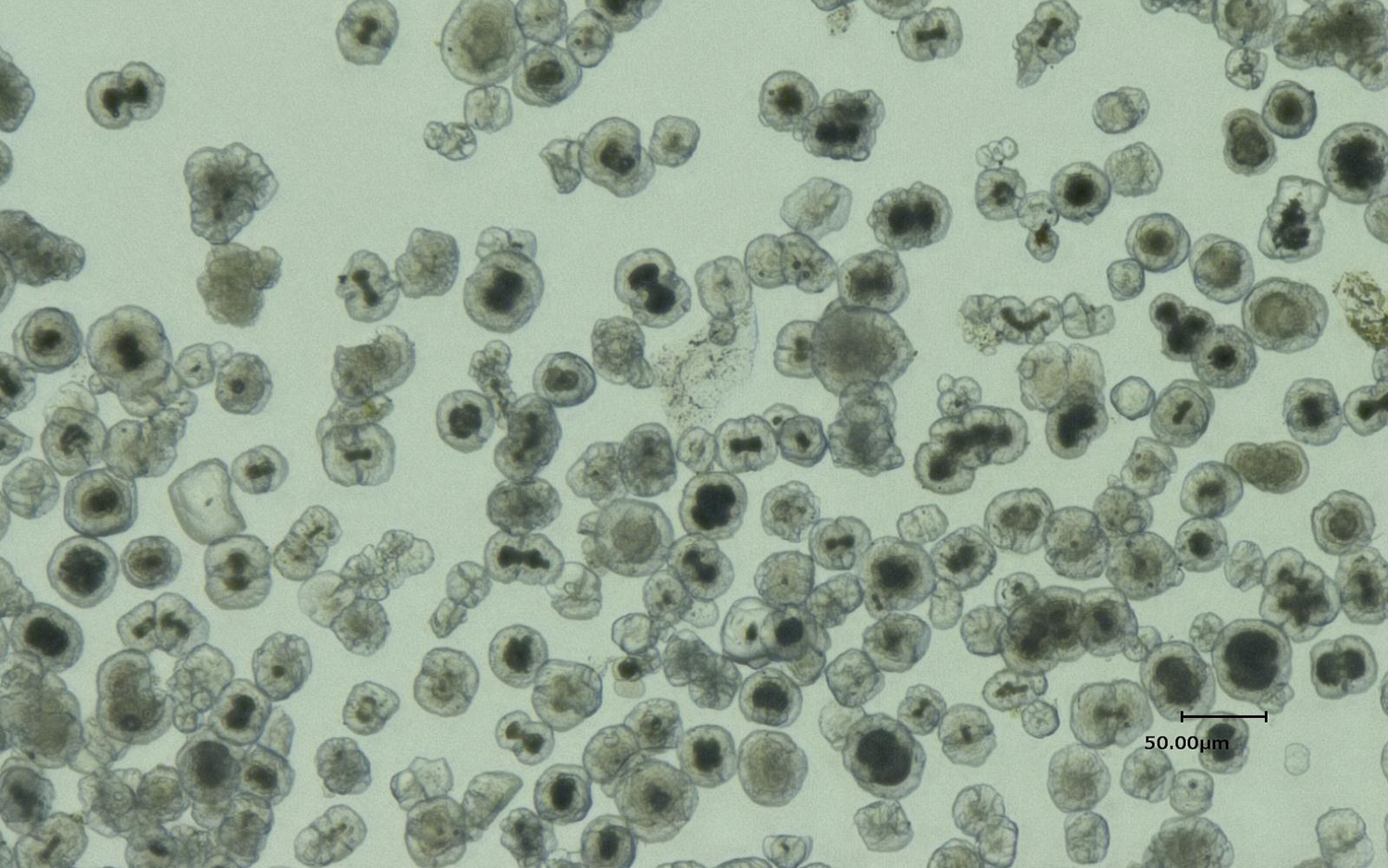

While the hydrates were quite large, measuring up to 16 feet (5 meters) long, the dolomite grains were tiny — about 30 microns, or 0.001 inches, in diameter, Snyder said. The researchers discovered the dolomite in residue left behind after they chemically separated the hydrates into gas and water.

Fluorescent staining of dark cores in the grains revealed that they contained genetic material, which glowed under UV light. It represented "high concentrations" of microbial matter, the scientists reported at the AGU meeting.

Microbes are known to live around gas hydrates; nevertheless, it was entirely unexpected to find these nested microbial tenants inside mineral grains that were inside the hydrates, Snyder said. The staining couldn't show whether the microbes were alive or not, and microbiologists are currently working to interpret the microbial DNA and identify the microbes, according to the presentation.

Because the microbes are effectively sealed inside a "pristine environment," scientists can be fairly certain that the organisms were naturally present in that area, and were not accidentally introduced by scientific equipment or human intervention, according to Snyder.

Though this is the only known evidence of microorganisms encased in dolomite crystals, there may be other microbial opportunists elsewhere in the oceans, growing in saline chambers in gas hydrates, the scientists reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, temperature and pressure conditions on other planets such as Mars could also be just right for shaping gas hydrates, which could potentially serve as homes for Martian microbes, the researchers wrote.

Microbe-housing dolomites discovered in the sea of Japan aren't very different from minerals found in Martian meteorites; this suggests that the Red Planet might present opportunities for microbial life to survive as it does inside dolomites on Earth, Snyder said.

- Gallery: Rainbow of Life in Great Salt Lake

- Magnificent Microphotography: 50 Tiny Wonders

- 7 Most Mars-like Places on Earth

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.