Alien Architects Didn't Build This Pre-Incan Complex, 3D Models Show

A sprawling pre-Incan stone structure in western Bolivia was once so impressive that its magnificence was described as "inconceivable" by Spanish conquistadors in 1549. Since then, centuries of looting reduced the formerly breathtaking building to scattered ruins, but scientists recently restored the enormous structure to its former splendor — as a 3D model.

Known as Pumapunku ("gateway of the puma" or "gateway of the jaguar" in the local indigenous language), the building was part of the ancient city of Tiwanaku, a bustling metropolis of the Andes from A.D. 500 to A.D. 1000.

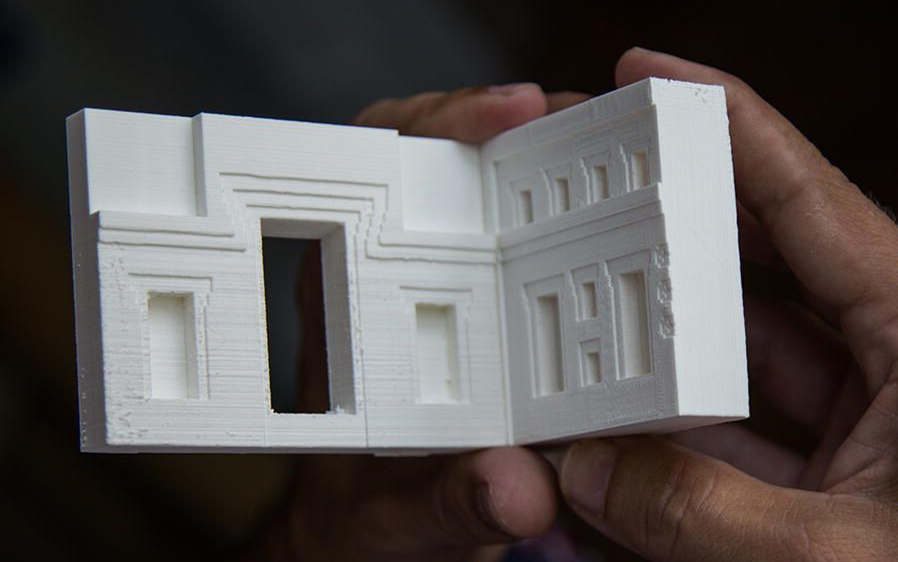

Researchers dug deep into historical records on Pumapunku that scholars had consolidated over 150 years, virtually reconstructing what they could from notes, descriptions, images and clues left behind in the tumbled stones and foundation slabs at the site. Eventually, a complete Pumapunku appeared for the first time in centuries — first as a digital model, then 3D-printed at 4 percent scale, Alexei Vranich, an archaeologist with the University of California, Los Angeles, reported in a new study. [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

By 3D printing scale models of the building parts, Vranich and his colleagues could explore how structures may have fit together through trial and error. This process is much more difficult to do with virtual models — which are less intuitive to manipulate and interpret — and is impossible to accomplish with the ruins' massive rocks, according to the study.

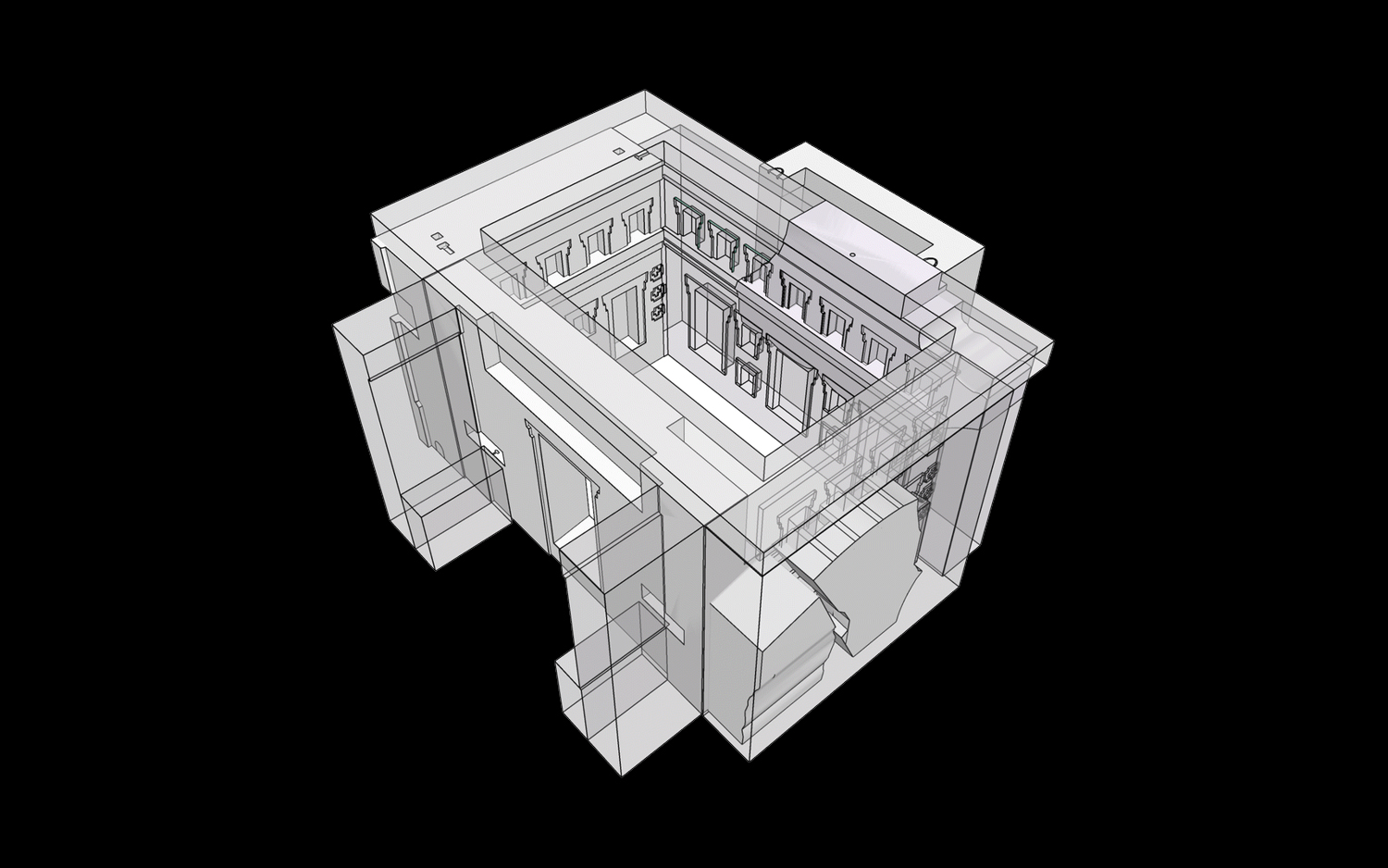

Vranich's results not only presented a near-complete Pumapunku, they also delivered "a solid piece of evidence" negating persistent rumors that the site was built by visiting extraterrestrials — so-called believers claimed that its architecture was unlike any other known structures on Earth, so it must have been engineered by alien architects, Vranich explained.

However, when the model of one building was assembled, its form was "immediately recognizable" as a design found in buildings at two nearby sites, Vranich wrote in the study.

In its heyday, Pumapunku was a sizable complex of plazas and ramps adjoining a massive, T-shaped platform, and it featured gateways and windows carved from single blocks of stone, according to Vranich.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But over hundreds of years, the complex was plundered over and over again. Reconstruction efforts in 2006, though well-intended, only made things worse. The project's archaeologists were under intense political pressure to finish quickly, and the results didn't conform to the archaeological record, sowing even more confusion about what Pumapunku used to look like, Vranich reported.

"There isn't a single stone in place," Vranich told Live Science in an email. "All the blocks have been moved, or were never placed in their intended place. Several have been lost, and others have been heavily damaged." And since the complex's design was thought to be unique, there were no other examples to inform their reconstruction, Vranich explained.

For the new study, the team pored over measurements and references from historical records "in different languages and varying degrees of legibility," translating the results into a virtual modeling program that focused on the geometry of the fragments.

"This needed to be millimeter accuracy," Vranich said in the email.

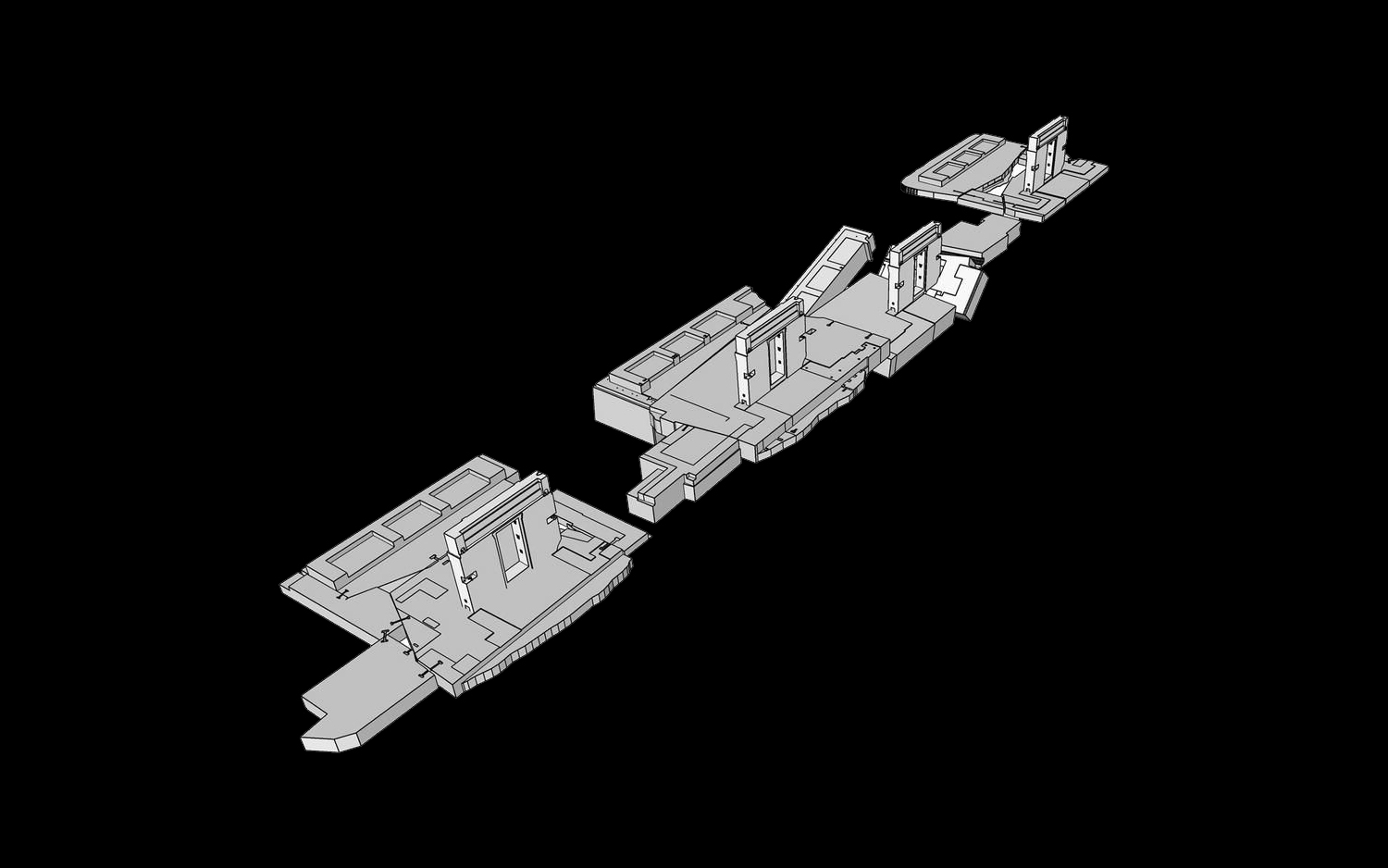

From that, they printed out 150 pieces, separated them into architectural sections and then organized them according to size, shape and thickness, noting if they were ornamented or if they had grooves to hold metal clamps.

The pieces were then assembled on a large slab representing Pumapunku's central platform, measuring — at 4 percent scale — 10 inches wide by 59 inches long (30 centimeters by 155 cm). The scientists assembled the buildings like they would a puzzle, and the tactile nature of the printed pieces helped them to intuitively discover how they fit together, according to the study.

"Occasionally, a new fit would be found and added in a cumulative to the virtual model on the computer," Vranich said. Adjustments to that model are still underway, as new blocks are measured at the site in Bolivia, and the information is uploaded online.

Printing 3D models of a site is a far less expensive undertaking than bankrolling new excavations; the total cost of the 3D-printed model of Pumapunku was only about $1,200, Vranich reported. Creating digital models and archiving them online also makes the site accessible to researchers in other parts of the world, he added.

And for investigating large complexes like this one, miniature models offer a unique opportunity to experiment with how the different structural pieces might be assembled, which would otherwise be impossible to explore. This offers "fresh and often unexpected insights" into the elaborate constructions produced by civilizations from the distant past, Vranich wrote in the study.

The findings were published online Dec. 13 in the open-access journal Heritage Science.

- 24 Amazing Archaeological Discoveries

- In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World

- Tiwanaku: Pre-Incan Civilization in the Andes

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.