Ice Age Graveyard Holds the Bones of Mammoth Nursery Herds That Died at Watering Hole

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Upward of 20 mammoths may have succumbed to disease from a poop-infested watering hole in Waco, Texas, during a severe drought in the last ice age. The new findings counter a past interpretation of this mammoth graveyard that suggested the animals died in a flood.

A new chemical analysis of mammoth teeth, as well as horse and bison chompers, from the 67,000-year-old graveyard, suggests that the thirsty animals converged at a water source in what is now Waco before they bit the dust.

The dental analysis also contained another bombshell: It revealed that the adult and juvenile mammoths weren't from one nursery herd, as was previously thought, but rather from two or more herds, said study researcher Don Esker, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Geosciences at Baylor University in Waco. [Mammoth Resurrection: 11 Hurdles to Bringing Back an Ice Age Beast]

Esker presented the research, which has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, on Wednesday (Oct. 17) here at the 78th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

Mammoth graveyard

Waco's mammoth graveyard is famous among paleontologists. The site contains the remains of 24 juvenile and adult Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi). In 2015, it became a protected national monument.

Hoping to learn more about the mammoths buried there, Esker looked at a single mammoth tooth, analyzing its isotopes (isotopes are variants of an element that have different numbers of neutrons in their nucleuses). The results were surprising, he said. About seven years before the animal died, the isotopes in this tooth matched those found in bedrock located about 100 miles (170 kilometers) southwest of Waco, in the Austin, Texas, area, Live Science reported last year. The mammoth would have absorbed these isotopes by munching on vegetation growing in the bedrock.

The trip from Austin to Waco was a long way for a mammoth to travel, Esker said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

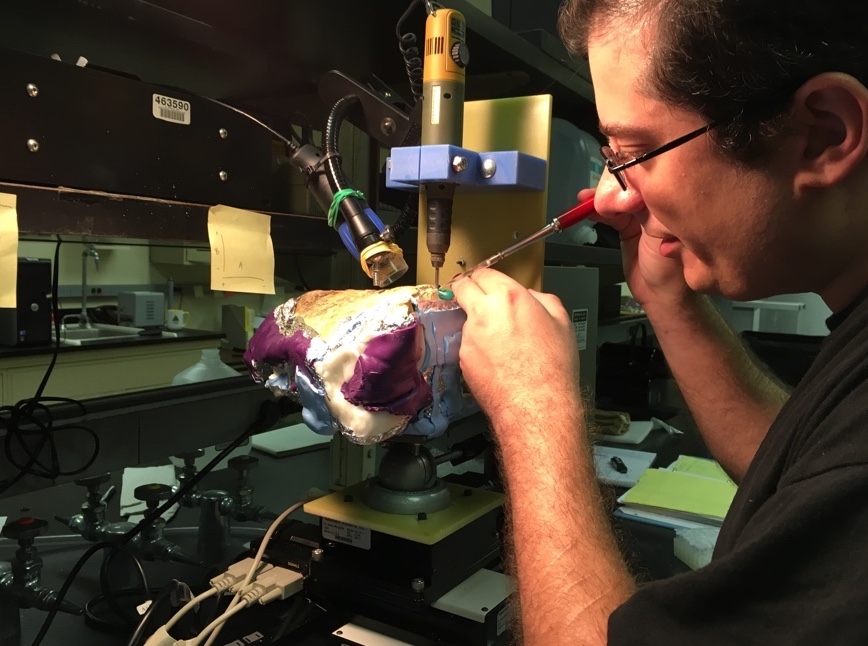

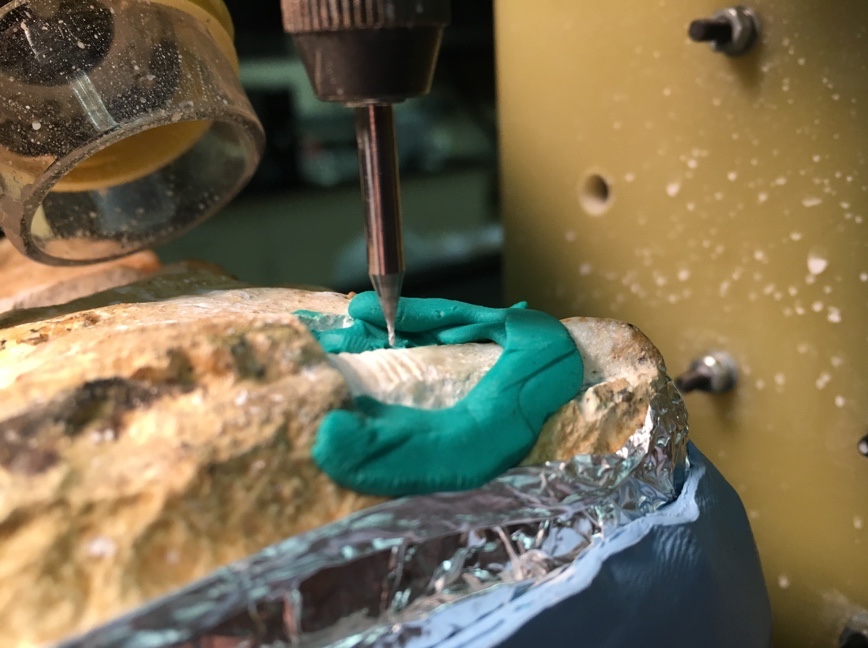

In the latest phase of his project, Esker got tiny samples from the teeth of two more mammoths, a bison and a horse whose remains lay in the Waco graveyard. He also got samples from a control mammoth from another site in Waco that died at a different time. Then, Esker took the teeth to East Tennessee State University, where he could use the only known high-precision micromill, which would help him drill miniscule samples from the teeth. (Esker said he tried to fly from Texas to Tennessee, but the airline wouldn't let him bring the teeth in his carry-on bag. "So, I got off the airplane and I drove 17 hours to the university" he told Live Science.)

Once at the Tennessee site, Esker worked with Chris Widga, head curator at East Tennessee's Natural History Museum. Widga had invented a computer-controlled micromill that could drill tiny samples, each representing 10 days of enamel growth, from each tooth.

"It's a really amazing system," Esker said.

Next, Esker sent the samples to Doug Walker, co-director of the Isotope Geochemistry Laboratories at the University of Kansas, for a strontium-isotope analysis. "[The results] kind of made my jaw drop," Esker said, "because they were not what I was expecting."

The animals in the graveyard had barely moved more than 40 miles (60 km) away from that spot during their lifetimes. The control mammoth "seems to have basically stood in one spot and munched its entire life," Esker said. "I'm exaggerating, but not too much." [Photos: Ice Age Mammoth Unearthed in Idaho]

Mammoth mystery

So, why were the new results so different from those taken from the first mammoth, the one that had traveled from the Austin area?

One possible explanation is that the first analysis was contaminated, Esker said. He didn't use the high-precision micromill technique on the first tooth, so for consistency's sake, Esker said he plans to reanalyze the first tooth on the micromill to see if the Austin results hold up.

However, if the results hold true, this finding indicates that there is more than one mammoth nursery herd in the Waco graveyard, Esker said. [See Images of the Baby Woolly Mammoths]

This finding prompts another question: Why were there so many nursery herds in one spot? One hypothesis is that there was a drought. "Maybe Waco National Monument is the last good watering hole in central Texas," Esker said. "The mammoths are congregating there and dying."

There is another idea, introduced by Dava Butler, a graduate student in science education on the paleo track at Montana State University, but more research is needed to see if that explanation holds up, Esker said. Bulter proposed that it's possible that with all of the animals pooping there, the watering hole was a prime location for Microcystis, an extremely poisonous blue-green algae.

"Maybe what we've got here is all of these animals congregating around a watering hole, eutrophication [nutrients from poop entering the water] happening and an algal bloom" occurring, killing the animals there, Esker said. "That's why they're not going elsewhere to look for other water."

Moreover, recent analyses of ancient aquatic reptiles at the site reveal strange conditions that are reminiscent of algal poisoning. Reptiles have a slower metabolism than mammals, like mammoths, which means it takes longer for them to die from poisonous algae, Esker said. And because these animals die more slowly, they have more time to develop health conditions, he said. "There are lots of other things that could have caused these pathologies, but it is consistent with what we see with Microcystis," Esker said.

Next, Esker said, he's planning to look for markers of Microcystis in the soil, as well as investigate more ancient teeth.

"Providing I can replicate these [isotope] results [for the first mammoth tooth] with the new machine, there's more than one nursery herd at that site," Esker said. "And that goes better with a drought than a flood, because you generally don't have animals congregating to die in a flood."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus