These Tiny Burrows Might Be Some of the Oldest Fossils on Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

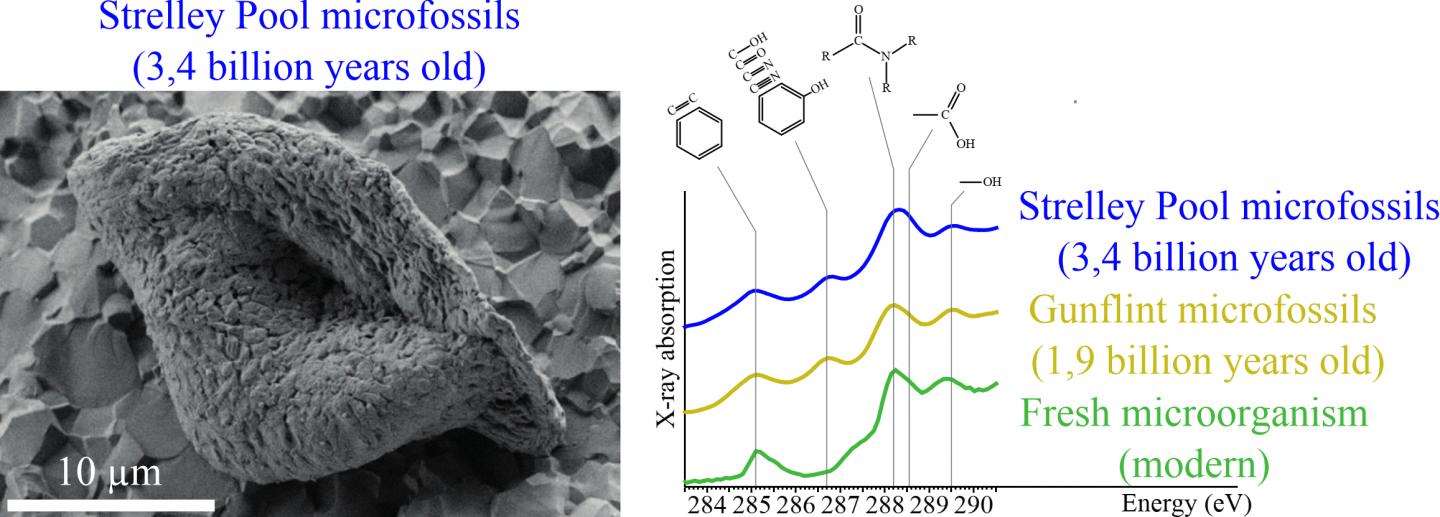

Tiny filaments burrowed in 3.4-billion-year-old rocks may be evidence of some of Earth's earliest life, scientists argue in a new study. But not everyone is convinced these burrows are fossils of ancient lifeforms.

These so-called microfossils, found in a shallow lake known as Strelley Pool in Western Australia, have been a source of contention for decades, with some scientists arguing that the mysterious tunnels were forged by volcanic processes, rather than primordial life.

The authors of the new study say their analysis of the rocks — which date to the early Archean eon, 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago — "all but confirms" that these Strelley Pool microfossils were once home to some of Earth's earliest life-forms.

The research, published in the peer-reviewed journal Geochemical Perspectives Letters and presented Aug. 16 at the Geochemical Society's Goldschmidt Conference in Boston, was conducted by a team of scientists led by study author Julien Alleon, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [In Images: The Oldest Fossils on Earth]

It's a hard rock life

The team analyzed the ancient structures found in the hard rock deposits, called cherts, of Western Australia's Strelley Pool Formation using advanced microscopy and spectroscopy techniques. The team compared the Strelley Pool filaments with similar structures made by modern bacteria, as well as with 1.9-billion-year-old microfossils from Canada's Gunflint Formation in Ontario, Canada. The Strelley Pool filaments contained organic molecules with similar chemical features to both of the other samples, suggesting all three were made by the same — biological — process.

"This is exciting work, with the new types of analyses providing compelling evidence that the cherts contain biogenic microfossils," or fossils made by living organisms, Vickie Bennett, a professor of geochemistry and cosmochemistry at the Australian National University, who was not involved in the research, said in a statement. "This is in line with other observations for early life from the Strelley Pool rocks." The results confirm the minimum age for life on Earth is 3.4 billion years, Bennett added.

Still, techniques used by Alleon and his team "are not applicable to the older rocks that host the claims for the oldest terrestrial life," Bennett said. So the new techniques won't resolve a debate about separate rocks from Labrador, Canada, dating to between 4.29 billion and 3.77 billion years ago, that some researchers say contain traces of Earth's earliest life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But not all scientists are convinced that even the Strelley Pool structures are biological in origin. Alison Olcott Marshall, an assistant professor of paleo-biogeochemistry at the University of Kansas, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science that, while the team's data do reveal that the structures are composed of carbon- and nitrogen-containing compounds, that is not unique to biological material.

"I would say that the authors make a convincing case that these are carbonaceous structures that are likely syngenetic," meaning the burrows formed at the same time as the surrounding rock, she told Live Science by email. But before definitively calling these rocks microfossils, she would like to see the same type of analysis that was done on the filaments also performed on the rock surrounding them, Olcott Marshall said.

That's because there are processes other than life that can put carbon in rocks. For instance, in older rocks from the Pilbara Craton, the geological formation that holds the Strelley Pool filaments, scientists have found that the surrounding rock contains multiple generations of carbon-containing materials, Olcott Marshall said. That would mean the carbon in the microstructures may not have been made by ancient life-forms, after all, she said.

Alleon acknowledged this point but argues it doesn't discount his team's conclusions. "Carbon- and nitrogen- containing compounds are not unique to life," he told Live Science in an email. "What we show is that the Strelley Pool microfossils have both nitrogen-to-carbon ratio and molecular signatures similar to younger biogenic microfossils from the Gunflint Formation. Their chemistry is thus consistent with fossilized microorganisms that have been only slightly degraded by geological processes."

Still, Olcott Marshall told Live Science that this new research has not settled the debate on these or older microstructures.

"Given how altered Archean rocks are, and how few localities there are to sample, I think it will be hard to ever finally close the book on this debate," Olcott Marshall said. "Instead, I think people will continue to use new techniques to write new chapters in this ongoing story."

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus