This Light Therapy Could Zap Away Chronic Pain One Day

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Just flicking on a light might one day provide pain relief to some patients with chronic pain, early research in animals suggests.

The research focused on a type of chronic pain called neuropathic pain, which results from damage to or dysfunction of the nervous system, according to the Cleveland Clinic. People with this condition may experience severe pain from even the lightest touch — for example, if something gently brushes against their skin.

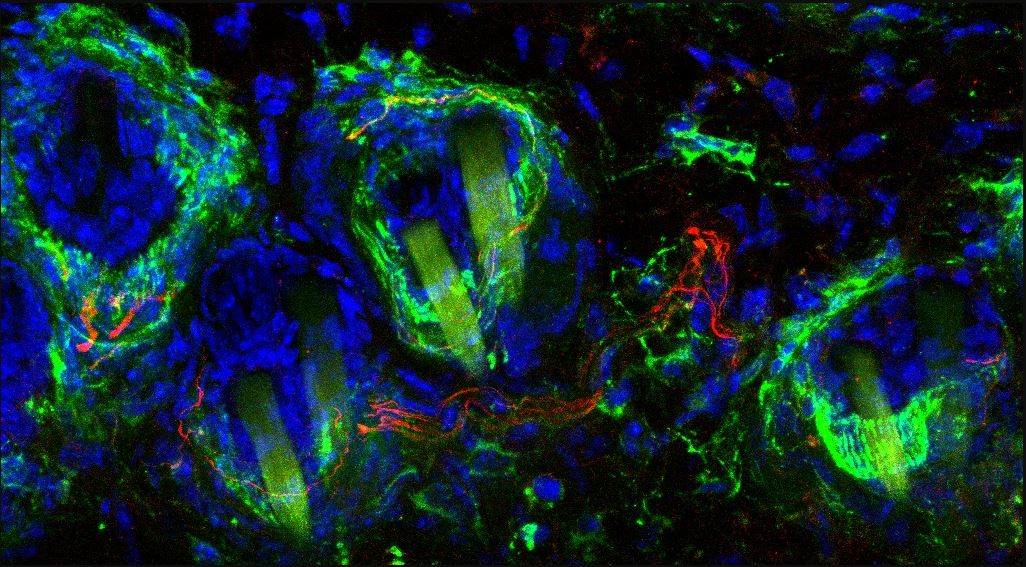

In the new study, researchers in Italy first identified the type of nerve cell that appears to cause this sensitivity to gentle touch in mice. Then, they developed a light-sensitive chemical that binds to this nerve cell.

When mice with neuropathic pain were injected with this chemical, and then had a near-infrared light shined on their bodies, the treatment appeared to lead to pain relief. Normally, mice with neuropathic pain would quickly withdraw their paws when they were gently touched, but after the therapy, the mice showed normal reflexes upon gentle touch, the researchers said. [5 Surprising Facts About Pain]

The light therapy works by clipping off the nerve endings of the targeted cells, thus desensitizing them. "It's like eating a strong curry, which burns the nerve endings in your mouth and desensitizes them for some time," study leader Paul Heppenstall, a group leader at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Rome, said in a statement.

The therapy specifically targets the nerve cells that are sensitive to gentle touch. Other nerve cells — such as those that sense vibrations, cold or heat — are not affected by the light therapy, the researchers said.

The treatment is temporary; in the mice, the nerve endings grew back after about three weeks, and the animals became sensitive to gentle touch again.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because the new study was done in mice, much more research is needed to see if the therapy will also provide pain relief to people with neuropathic pain. For instance, the researchers still need to confirm that the cells that cause sensitivity to gentle touch are the same in mice and people, and examine the safety of the treatment.

"A lot of work needs to be done before we can do a similar study in people with neuropathic pain," Heppenstall said. But the researchers want to develop the technology further," with the hope of one day using it in the clinic," he added.

The study was published today (April 24) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus