As World Warms, America's Invisible 'Climate Curtain' Creeps East

A climate boundary divides the United States — and it's on the move.

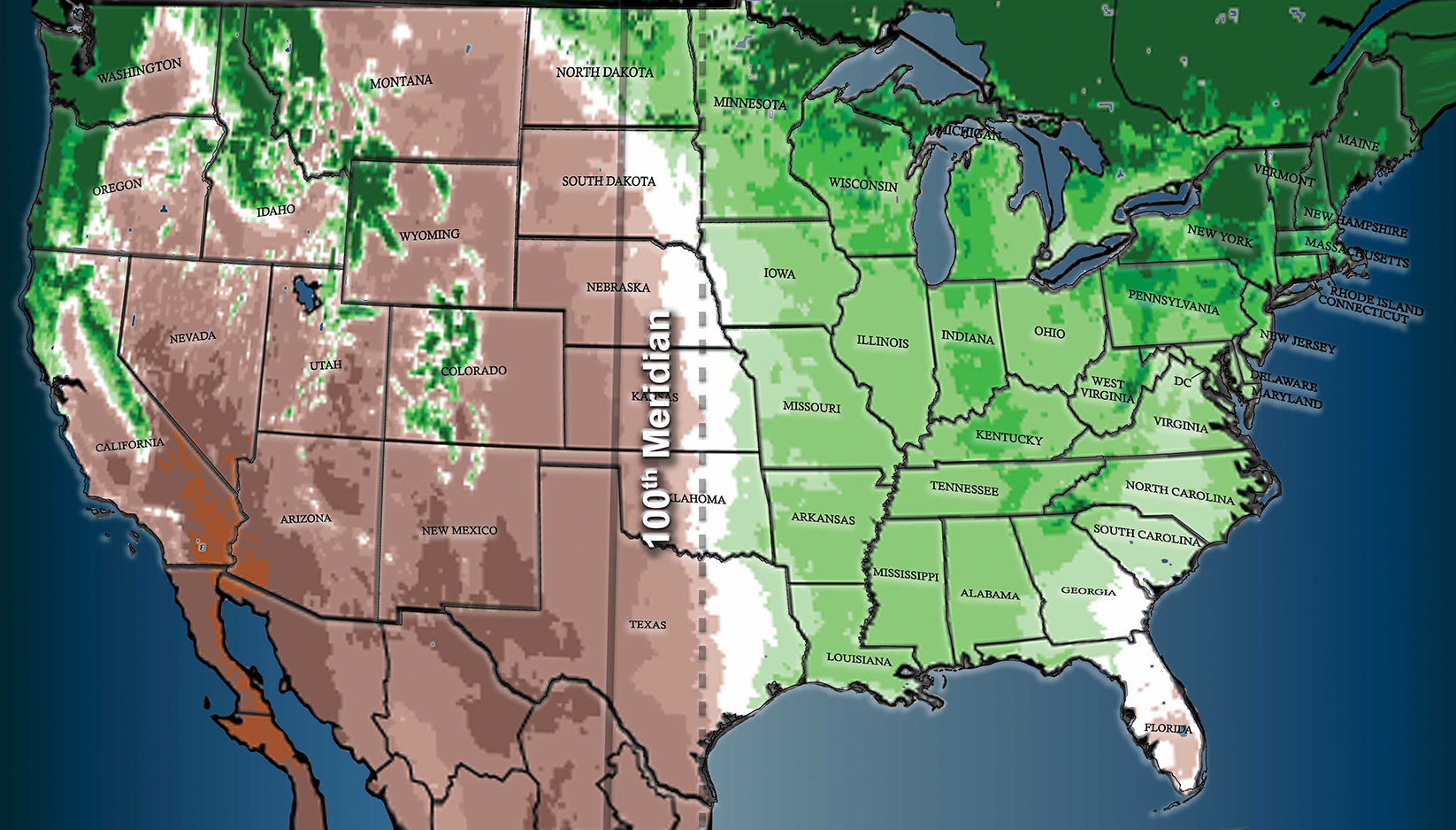

During the late 19th century, land management officials conceived of the invisible boundary along the 100th meridian (a longitudinal line), which runs north to south, to mark the beginning of the U.S.'s Great Plains region. The invisible border bisects all of North America.

But the 100th meridian is also a boundary between two profoundly different climates: eastern humidity and western dryness. And scientists have noticed an alarming trend. The border is shifting, with the arid conditions on the west slowly expanding eastward, nudging the boundary by about 140 miles (225 kilometers) from its original position. [Map Shows How Climate Change Will Affect Health Across US]

"A wonderful transformation"

The American geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell visited and reported on the 100th meridian in 1878, arguing that the U.S. government should establish irrigation strategies to compensate for drier conditions to the west of the boundary, researchers explained in a new study. Powell wrote that he observed changes in landscape and scenery along the boundary as he traveled from east to west, seeing the lush greenery and flowers give way to ground that "gradually becomes naked," calling it "a wonderful transformation," the study authors reported.

But is the actual boundary as dramatic as Powell described? To find out, scientists examined data on soil moisture, crop and vegetation cover, precipitation, and atmospheric conditions that shape the distribution of water across the continent. The researchers discovered that Powell's evaluation of the 100th meridian as "an arid-humid divide" was highly accurate and that this division is still strongly evident, with effects on the types of crops that can succeed on either side of the divide.

For example, wetter conditions favor corn, which makes up 70 percent of the crops grown to the east of the border. However, agriculture in the drier west is dominated by wheat, which grows well under arid conditions, according to the study.

Along the boundary, soil moisture showed "a sharp transition," as did the type of vegetation likely to grow there in the absence of human activity, the scientists noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

North America's geography and the interplay of global wind patterns explain why eastern regions are wetter than the plains. During the winter, storms that brew in the Atlantic Ocean carry moisture inland, but they can't travel far enough to soak the west. And during the summer months, when moisture moves northward from the Gulf of Mexico, winds carry that moisture to the east, so the west again comes up short.

Meanwhile, much of the moisture that originates in the Pacific Ocean stops at the Rocky Mountains, before it reaches the Great Plains.

Drying out

But this boundary is changing, according to data collected since around 1980 and described in the two-part study published March 21 in the journal Earth Interactions. Dry conditions are expanding, shifting the border to the 98th meridian, around 140 miles east, researchers explained in the study's second part.

The shift can be explained by changing precipitation patterns and higher average temperatures that make moisture evaporate from the soil more rapidly than in the past, the study said.

Both parts of the study highlight the different conditions that have long existed side by side along this unseen border, suggesting the ways climate shaped colonization and agriculture in North America. But as climate change continues to heat up our planet, human communities and farms may need to adjust to long-term changes in conditions — and potential crop failure — should dryness continue to encroach into eastern lands, the study said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.