How (and Where) Did Hannibal Cross the Alps? Experts Finally Have Answers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

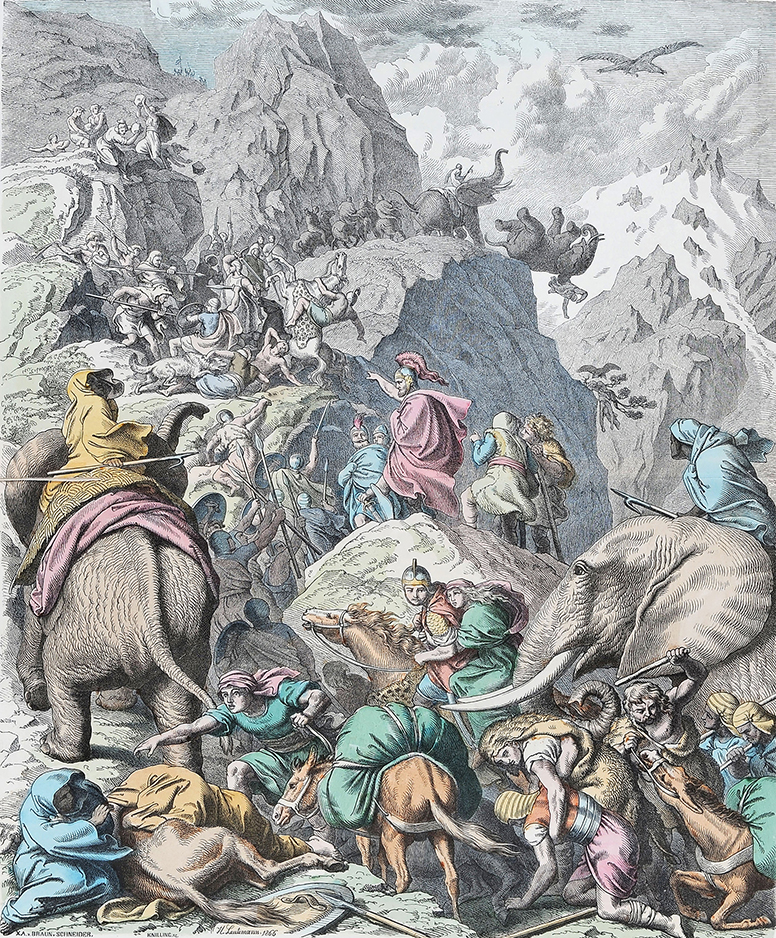

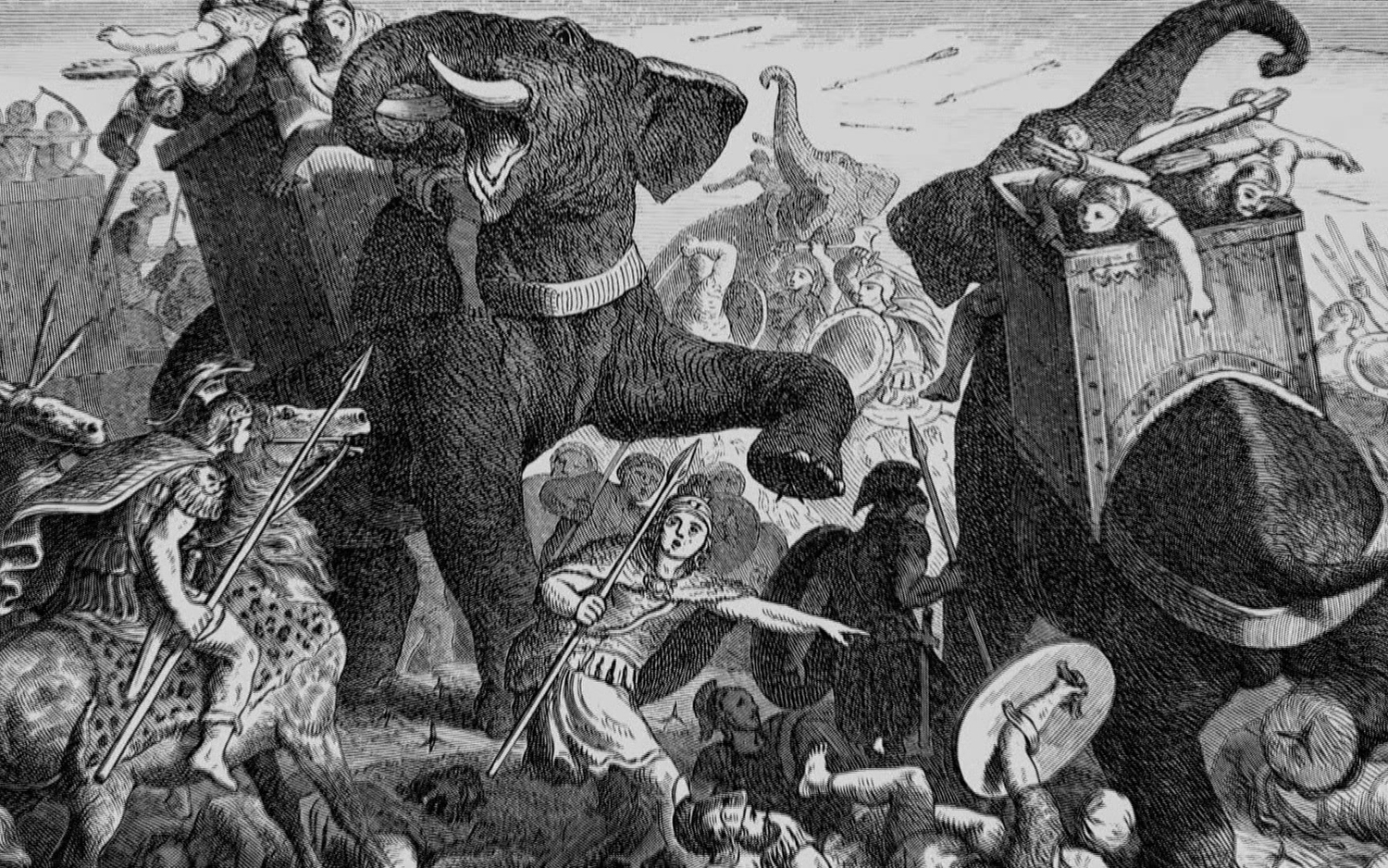

For over 2,000 years, historians have argued over the route used by the Carthaginian general Hannibal to guide his army — 30,000 soldiers, 37 elephants and 15,000 horses — over the Alps and into Italy in just 16 days, conducting a military ambush against the Romans that was unprecedented in the history of warfare.

Such an achievement required careful planning and strategizing, but with little physical evidence of the journey available today and few recorded details of the crossing, uncertainty remains about how it was accomplished.

However, in "Secrets of the Dead: Hannibal in the Alps," a new documentary airing on PBS tonight (April 10), a team of experts takes a fresh look at Hannibal’s incredible trip across treacherous mountain terrain. Together, they re-create his long-lost route and reveal the latest discoveries about his historic accomplishment — and depict the famous elephants that played a critical part in his victory against the Romans. [Beasts in Battle: 15 Amazing Animal Recruits in War]

In 218 B.C., when the crossing took place, the powerful nations of Carthage and Rome were at each other's throats. To defeat the Romans, Hannibal did the unthinkable — he led an army through a mountain region spanning about 80,000 square miles (over 207,000 square kilometers) — and descended on Rome from the north, where the nation least expected an attack.

For the documentary, the production team assembled archaeologists, paleontologists, animal trainers and mountaineers, re-creating Hannibal's route on foot and testing evidence and methods along the way, the filmmakers said in a statement.

Finding the path

The most obvious route for Hannibal to have taken through the Alps is called the Col du Clapier, known in antiquity as the Way of Hercules, historian and archaeologist Eve MacDonald, a lecturer in ancient history at Cardiff University in the U.K., told Live Science.

MacDonald, who appears in the documentary, explained that the team uncovered evidence suggesting that Hannibal took a much more dangerous and extreme route — the Col de la Traversette — which was at a higher elevation and had a much steeper ascent and descent, but offered far quicker passage through the mountains, despite the extra risks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That's key — it was the fastest route, and the least expected," MacDonald said.

This also supports historical accounts by the Greek historian Polybius, who lived from around 200 B.C. to 118 B.C., and who described Hannibal choosing "the highest paths" for his army, MacDonald added.

The clues that pointed to Hannibal's path were preserved not in recovered records or military artifacts, but in soil deposits along the Col de la Traversette, in miry areas that may have been used long ago by the army's many animals as watering holes — and as a toilet. Compounds that are found in horse manure were plentiful in the sediment, suggesting that thousands of years ago, an army-size group of horses likely relieved themselves while resting, according to the filmmakers' statement.

Beasts of burden

Speculation also lingers about Hannibal's war elephants and where they came from. Hannibal's beasts were long thought to be Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), due to prevailing myths that those elephants are more trainable than African elephants (Loxodonta africana and Loxodonta cyclotis), Victoria Herridge, an elephant expert for the documentary and a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum, London, told Live Science. [What's the Difference Between Asian and African Elephants?]

But that simply isn't the case. In fact, on coins from Carthage depicting realistic representations of elephants, the animals closely resemble the African species in the size and shape of their ears, and in their distinctive, saddle-shaped backs, raising the possibility that the Carthaginians were importing their elephants from northern Africa, Herridge said.

If that were true, Hannibal's elephants may have represented a smaller, now-extinct subspecies of African elephant; historical accounts described northern African war elephants as fearful of the bigger Indian war elephants, while modern Asian elephants are generally smaller than their African cousins, Herridge explained.

Elephants require vast quantities of food — about 220 lbs. (100 kilograms) per day — which the army would have needed to bring along with them, as there wasn't anything for the animals to eat along the way. But the elephants would likely have handled the terrain and the distance quite well, as they frequently have to cover great distances and cross mountain passes in both Africa and in the Himalayas, Herridge said.

Ultimately, Hannibal's brazen maneuver — elephants and all — couldn't save Carthage, which Rome defeated in the Second Punic War (218 B.C. to 201 B.C.). However, as this documentary demonstrates, his ambitious journey still fuels imaginations and raises intriguing questions about achieving the seemingly impossible — for people and for elephants.

"Secrets of the Dead: Hannibal in the Alps" airs April 10 at 8 p.m. EDT on PBS (check local listings) and is available to stream on April 11 via pbs.org/secrets and PBS apps.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus