Roman Change: Ancient Coins Reveal Rise of an Empire

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Rome wasn't born big. Back before it blossomed into an empire that sprawled across 2.2 million square miles (5.7 million square kilometers), twice the size of modern-day Argentina, Rome was an up-and-coming force threatened by a formidable city-state: Carthage.

Historians have long thought that Rome's wealth blossomed after Carthage— best known for the general Hannibal Barca's ill-advised decision to have his army traverse the Alps with almost 40 war elephants— was defeated by Rome in the Second Punic War (218 B.C. to 201 B.C.). Now, a new study of ancient coins provides evidence that this was, in fact, a critical turning point for Rome.

The wealth Rome received from booty and war reparations paid by Carthage helped fund Rome's budding empire. In addition, as part of the peace treaty, Carthage passed control over the Iberian Peninsula to Rome, which gave the Romans access to Spanish silver mines, according to a statement.

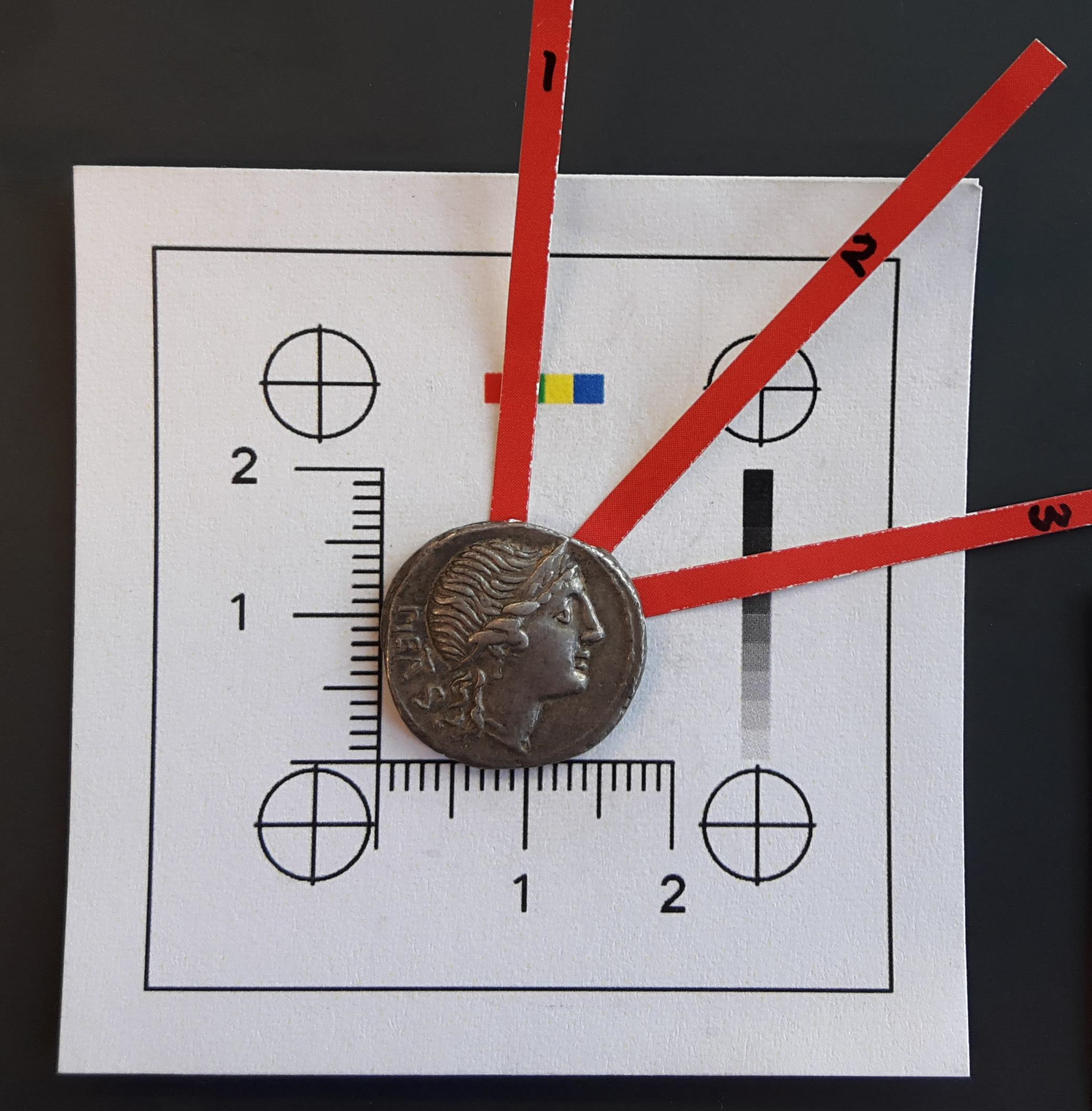

Katrin Westner, a postdoctoral researcher in archeometry (a branch of archaeology that focuses on dating ancient specimens) at Goethe University in Germany, and her team found that most of the Roman coins analyzed date to a period beginning during the Second Punic War. Those coins, the team discovered, were made of silver that probably came from Spanish mines, not from Greek colonies in southern Italy and Sicily. [Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire]

"It was kind of this 'hooray!' moment in the lab," Fleur Kemmers, a professor of ancient numismatics (the study of currency) at Goethe University, told Live Science,

The researchers analyzed the lead isotopes, the signature that marks different types of lead, of samples using mass spectrometry, from 69 coins from the period between 310B.C. to 101 B.C. This helped the scientists determine during which geological period the silver had been mined. (Since lead is either present in the ore from which silver is extracted or added as part of the extraction process, it is a useful indicator of the source of silver.)

The team then matched the time periods of the coins to the geological time periods when various ore deposits were formed in the western Mediterranean, including in Spain, France, North Africa, Italy and Asia Minor, which encompasses part of present-day Turkey and Armenia. The researchers found that of the 69 Roman coins they examined, 52 were most likely made from metal that came from Spain. These same 52 coins were also found to date between 209 B.C. and 101 B.C., which is significant because in 209 B.C. Rome conquered a Carthaginian stronghold in Spain—a turning point in the Second Punic War.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the silver in the coins before then came from mining districts in southern Italy and Sicily, which was not under Roman control, the period following the Second Punic War marked a new era for the Roman economy, the researchers said. Bolstered by war reparations and booty obtained by plundering cities, and then later by the ore from mines in conquered lands, Spanish silver contributed to Rome's transformation into a leading superpower, according to a statement.

"[Rome's wealth after 209 B.C.] really helped to promote this kind of thinking that wars actually are a financial investment that can pay off afterwards, if you win it," Westner told Live Science.

This study is part of a wider project to analyze 164 coins from across the western Mediterranean spanning the period between 550 B.C. to 101 B.C., in order to obtain more evidence of how political power can be traced through the metal supply.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus