Crashing Chinese Space Station Will Go Down Shooting — Fireballs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

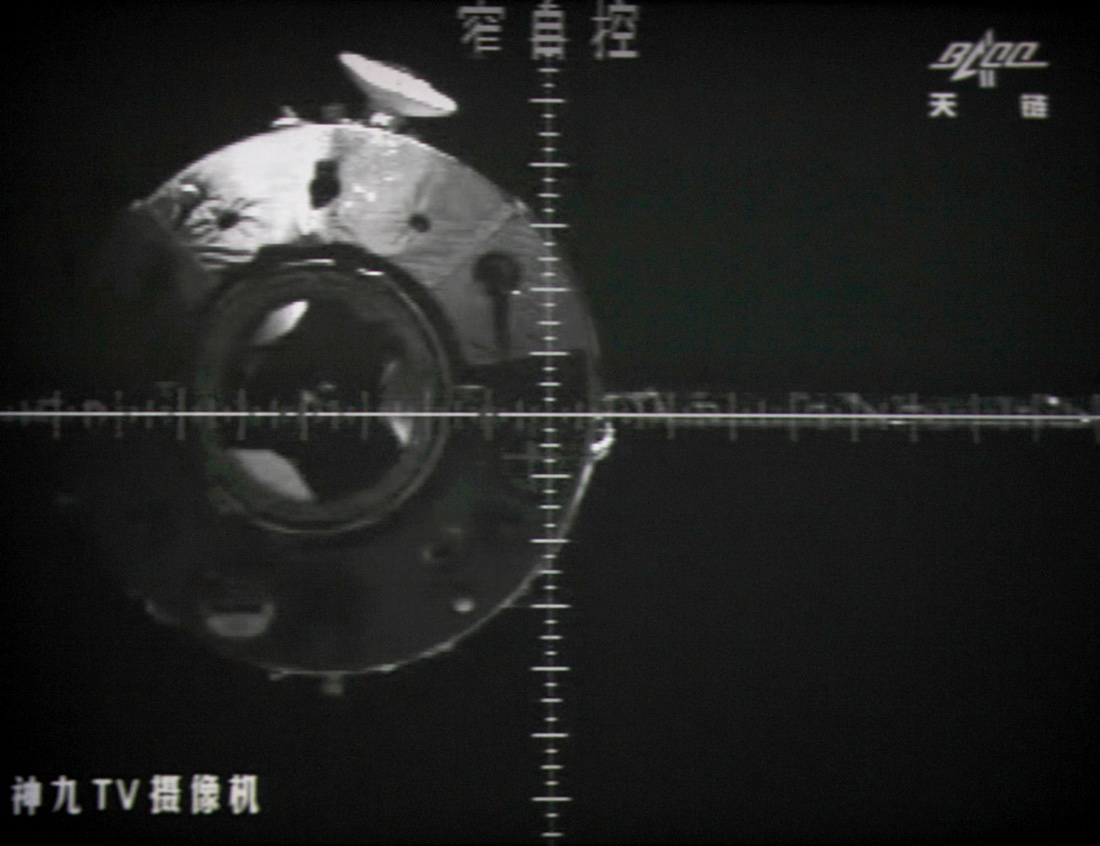

China's first space station, the bus-size Tiangong-1, is falling uncontrollably toward Earth, with a fiery plunge through our atmosphere expected sometime between March 30 and April 2. And the dive will, in fact, be a blazing one: Scientists expect that as the station burns up, it will generate huge fireballs visible from the ground.

Tiangong-1, which has attracted worldwide attention these past few weeks ahead of its demise, launched in 2011 and hosted two space crews before contact was lost with the craft in 2016. Since then, Tiangong-1 has been falling closer to Earth without control from Chinese space officials.

"Fireballs are almost certain," Harvard University astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell told Live Science in an email. McDowell is a frequent media commentator on Tiangong-1's descent, and he also works on NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory. [In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Crashing to Earth]

"What happens is that there are some dense sections of the lab connected together by a rather thin structure," McDowell said, explaining the source of the fireballs. "The thin structure melts first, turning the lab into a bunch — a few to a few dozen, depending — of independent pieces which melt and burn more slowly — fireballs."

Tiangong-1 is roughly 9.4 tons (8.5 metric tons), which is almost the same size as the Ukrainian Zenit rocket stage that re-entered our atmosphere over the Peru/Brazil border in January, McDowell said. So, that re-entry could offer some insight into what to expect from the Chinese space lab. Some parts from the Zenit rocket stage did land near Peruvian villages, SpaceFlight101.com reported. Villagers there reported "spherical" objects — likely the rocket's spherical tanks, which can survive re-entry, the website reported. [Chinese Space Station's Crash to Earth: Everything You Need to Know]

In addition to human-made objects, many tons of meteors hit Earth every year, mostly in the form of dust. Occasionally, larger rocky meteors break up in the atmosphere and hit the planet. The resulting meteorites are highly prized by collectors. In January, a small meteor broke up over Michigan, and collectors found pieces of the object on the ice within a day of its fall.

In a more spectacular example, a 56-foot-across (17 meters) meteor broke up over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013 with such force that it shattered windows and caused injuries to residents below.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Compared to a meteorite, the lab is coming in slower and at a much shallower angle," McDowell said. "The debris will be spread over hundreds of kilometers along the line of travel. You'll see the fireball when it is between 50 km and 20 km [31 miles and 12 miles] up, and any debris that doesn't melt all the way may hit a long way downrange."

Some observers have compared Tiangong-1's descent to the spectacular crash of NASA's 100-ton (91 metric tons) Skylab space station in 1979, which scattered debris in rural Australia. But McDowell said only a small portion of Tiangong-1 will survive and make it to Earth's surface. Because the space station weighs about 18,740 lbs. (8,500 kilograms), McDowell estimates that about 220 to 440 lbs. (100 to 200 kg) will survive the descent.

Originally published on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus