Here's What Happens When You Leave Surgical Sponges in a Person's Body for Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Sometimes, a bloated stomach is just gas or the result of something you ate. But for one woman in Japan, her abdominal bloating turned out to be caused by two surgical sponges that were left in her body years earlier, according to a new report of the case.

The 42-year-old woman told her doctors that she'd had symptoms of bloating in her lower abdomen for three years, the report said. Previously, she'd had two cesarean sections — one six years ago, and one nine years ago.

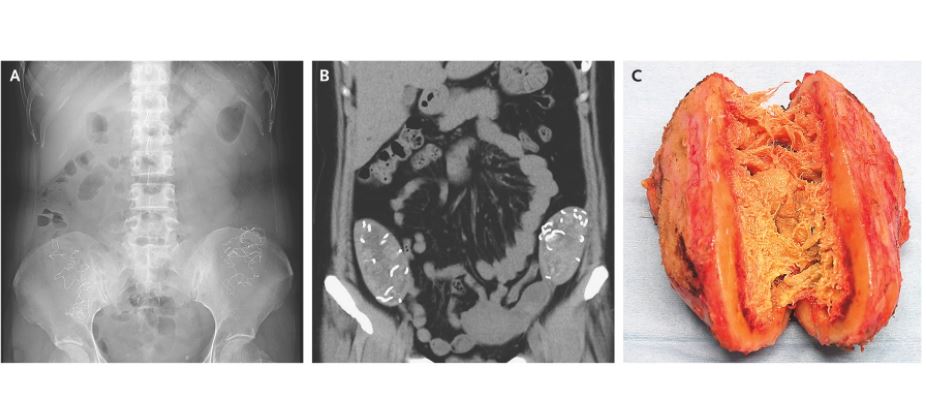

When doctors examined the women, they felt two masses near her right and left hip bones. She was sent for a CT scan of her abdomen, which revealed two masses filled with "hyperdense, stringy structures," according to the report, which was published today (Feb. 21) in The New England Journal of Medicine. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

To remove the masses, the woman needed to have surgery. During the operation, the doctors found the two masses in an area called the paracolic gutters, which are the spaces (on each side of the body) between the colon and the abdominal wall.

After the masses were removed, the doctors cut them open, revealing gauze sponges that were encased in "thick, fibrous walls," the report said.

These sponges turned out to have been left behind after one of the woman's C-sections, but it's not clear whether the error occurred during the woman's first operation, which was nine years ago, or her second, which was six years ago, said lead case-report author Dr. Takeshi Kondo, of the Department of General Medicine at Chiba University Hospital in Japan, who treated the patient for her abdominal pain. Still, Kondo suspects that both sponges were left during a single operation, rather than one from each operation.

During a C-section, an obstetrician may put surgical sponges in the paracolic gutters to prevent the intestines from getting in the way during surgery, Kondo told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Leaving a surgical instrument inside a patient's body is considered a "never event" in medicine — in other words, an event that should never happen — according to a 2013 review article on the topic.

These events are rare: The 2013 review found that the incidence of "retained foreign bodies" after surgery ranges from 1 in 5,500 operations to 1 in 18,760 operations.

But gynecological surgeries may come with a greater risk of these events, compared with other surgeries. A 2010 study found that girls under 18 who underwent gynecological surgeries, such as the removal of ovarian cysts, had four times the risk of coming out of surgery with a foreign object inside them as other children who'd had surgery.

This may be because areas of the pelvis are more difficult to reach and have more recesses to lose a sponge or small instrument, Dr. Fizan Abdullah, a pediatric surgeon now at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, told Live Science in a 2010 interview.

Kondo said a surgical checklist, in which surgeons count and recount the objects placed in and removed from a patient's body, may help prevent these errors.

The woman recovered from her surgery, and her bloating symptoms completely went away, the report said. She went home from the hospital five days after her surgery.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus