Flat Earth: What Fuels the Internet's Strangest Conspiracy Theory?

A believer in flat-Earth conspiracies took another shot at shooting himself toward the stratosphere in a homemade rocket. Once again, it fell flat.

"Mad Mike" Hughes, a self-proclaimed daredevil who rejects the fact that the Earth is round, posted a video on his Facebook page about two weeks ago saying that he planned to launch himself from private property to an altitude of 1,800 feet (550 meters) on Saturday, Feb. 3. Hughes had canceled and delayed launches before, so it wasn't really clear whether Saturday's event would happen. His homemade rocket sat on the "launchpad" in Amboy, California, for about 11 minutes before it … didn't go anywhere, as shown on a live video of the event.

Nevertheless, it spotlights a subculture that is increasingly gaining notoriety online.

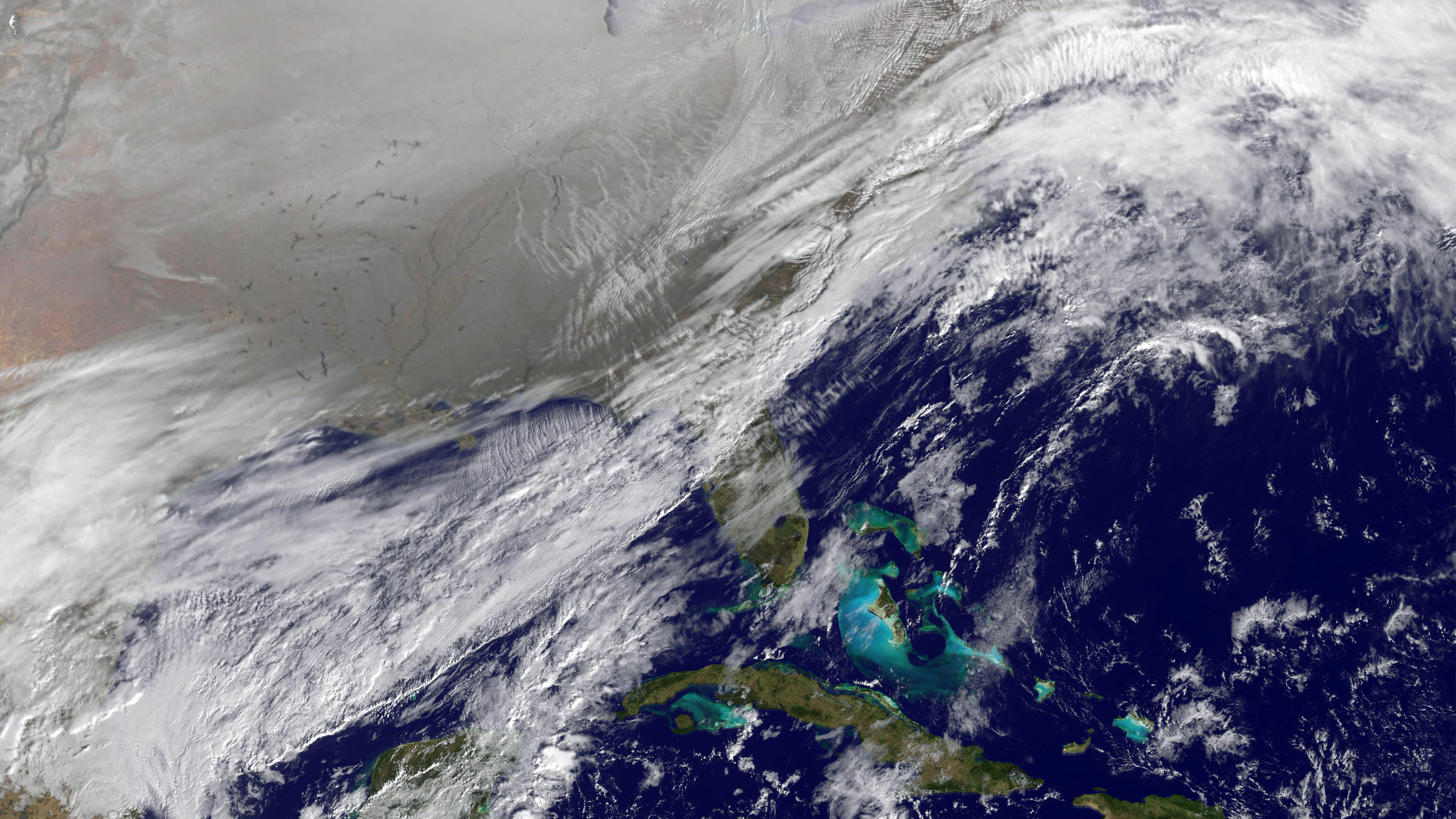

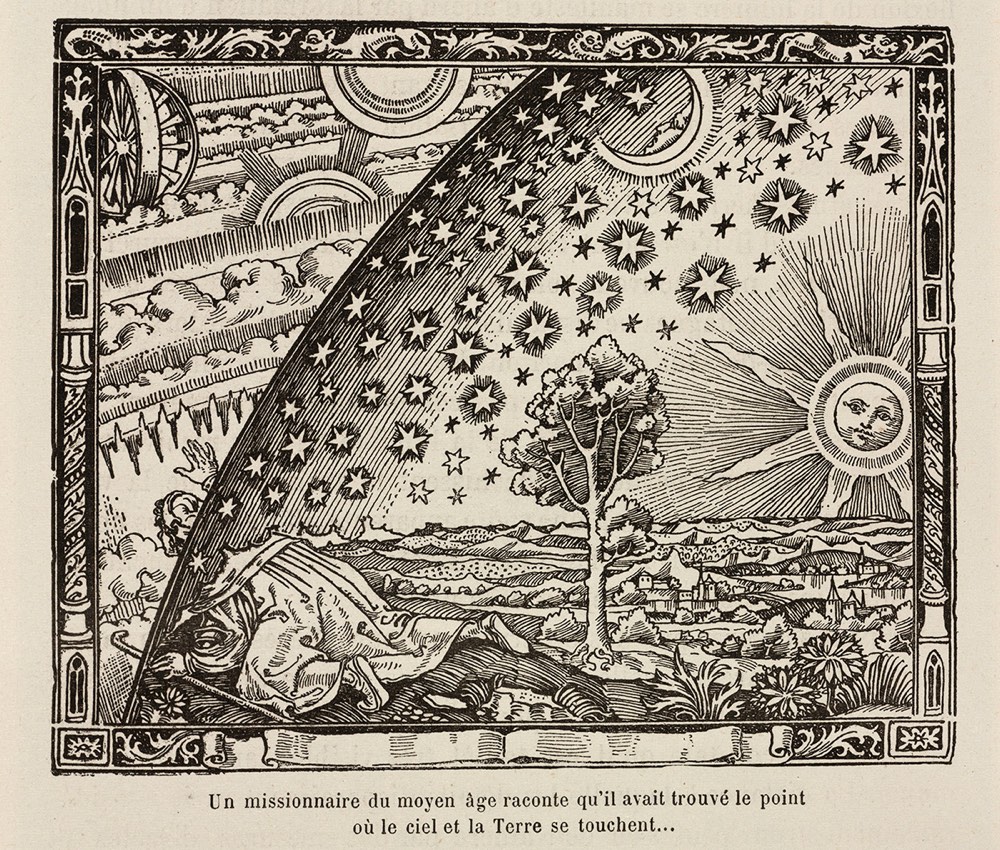

That subculture is flat-earthers, people who argue that centuries of observations that the Earth is round (including astronaut photographs from space and the fact that round-the-world travel itineraries work) are either mistaken or part of a vast cover-up. Instead, flat-earthers argue, the planet is a disk. Exactly what this looks like varies by who is theorizing, but many flat-Earth believers say that walls of ice surround the edge of the disk, and that the planets, moons and stars hover in a sort of dome-shaped firmament above Earth, much closer to Earth than they really are. [8 Times Flat-Earthers Tried to Challenge Science in 2017)

As conspiracy theories go, it's a pretty all-encompassing one. So what is the appeal? For many believers, it's a matter of distrust of the scientific elite and the desire to see the evidence with their own eyes. And, psychologists say, flat-Earth conspiracy theorists may be chasing many of the same needs as believers in other conspiracies: social belonging, the need for meaning and control, and feelings of safety in an uncertain world.

The draw of conspiracy

Flat-Earth theories aren't new; in the modern era, they date back to an English writer named Samuel Rowbotham, who came up with a variety of creative interpretations of cosmology in the mid-1800s. There was a smattering of interest in the 1950s with the creation of the International Flat Earth Society, but today's resurgence of the theory seems to derive from social media, said Viren Swami, a social psychologist at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England. Minor celebrities, such as rapper B.o.B and TV personality Tila Tequila, have boosted the conspiracy's profile by tweeting about their skepticism that the Earth is round. [7 (Easy) Ways to Prove the Earth Is Round]

The internet-era flat-Earth movement is new enough that no one has done any psychological research on it, Swami said, though one of his students is working on a project on the phenomenon now.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, psychologists have studied why conspiracy theories are appealing, in general. The reasons fall into three main categories, said Karen Douglas, a social psychologist at the University of Kent in Canterbury, England.

The first reason has to do with the search for knowledge and certainty. People who feel uncertain tend to be drawn to conspiracies, Douglas told Live Science. This happens on both small and large scales: When people are induced to feel out of control in a psychology study, they become more open to conspiracy belief, 2015 research found. There is also evidence that conspiracy beliefs spike during times of societal crisis, such as after the 9/11 attacks, according to a paper published last year in the journal Memory Studies.

Though imagining shadowy cabals behind every corner might seem scary, conspiracy theories also seem to offer believers the promise of control in the form of knowledge and insight that others lack, Douglas said.

"You have a need for security and control, and you don't have it," she said, "so you try to compensate for it."

Finally, conspiracy theories can give believers a self-esteem boost and allow them to feel good about the groups they belong to. Some studies suggest narcissism and conspiracy belief are linked, Douglas said, and many conspiracies divide the world into "good guys" (e.g., the moral YouTube star setting out to find the truth) and "bad guys" (e.g., the government, or a given ethnic group).

Rejecting the basics

People are often fairly self-aware about the underlying reasons they believe in conspiracies, said Michael Wood, a lecturer in psychology at the University in Winchester in England.

"One thing I've found interesting in my own adventures on the flat-Earth side of YouTube is, people are often pretty upfront about their motives," Wood said. They'll say that they find it more appalling to believe in the universe as a huge, uncaring place, and that it seems more reasonable to imagine Earth was made for humans like a perfect snow globe. [10 Times Earth Revealed Its Weirdness]

Some flat-Earth believers are motivated by religion, Wood noted; some harken back to biblical passages mentioning "the firmament" of the heavens. For others, the flat-Earth belief seems to grow out of other, space-related conspiracy beliefs, such as the belief that the moon landings were faked, Wood told Live Science.

"If you read flat-Earth discussion groups, people talk about NASA, and they really hate NASA," he said.

Part of the problem, Swami said, is that understanding the physics of the universe is very difficult, and flat-Earthers are, to some extent, right that science is elitist: It takes money, knowledge and time in higher education to be in a position to launch a satellite into space or understand the math that shows why the planet is round. (However, you can fairly easily prove it is round with home-based methods.) Flat-Earth theories simplify all the complexities and don't require believers to put any faith in science or scientists, Swami said.

Interestingly, studies involving children suggest that although humanity has known that the planet is round since the time of the ancient Greeks, it's not an intuitive belief. Elementary-school students will say that the world is round when asked, according to studies dating back to the 1970s and 1980s, but further questioning often reveals that their mental image of the round Earth is quite confused. They might believe, for example, that the Earth up in space is round, but obviously the one we walk around on is flat. Or they might say the Earth is round, but also that it's possible to fall off the edge. These contradictory beliefs were common in kids up to age 10 or so, according to a 1985 study. By 13, most kids had grasped the concept of a spherical Earth, the study found, though some were still a little flummoxed by how gravity worked.

Unfortunately, once a conspiracy belief is established, it's hard to change, said Swami; people tend to hold on to their beliefs. Arguments and discussions only tend to entrench those beliefs, as people tend to engage in what's called "psychological reactance," Swami said, spending time honing their own arguments and convincing themselves even further of their own rightness.

Prevention, instead, seems to be key, Swami said. Analytical and critical thinkers have been shown to be less susceptible to conspiracy beliefs, he said.

"It's really, really key that we teach properly critical-thinking skills and analytic skills," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.