Here's What You'd Look Like As Just a Nervous System

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

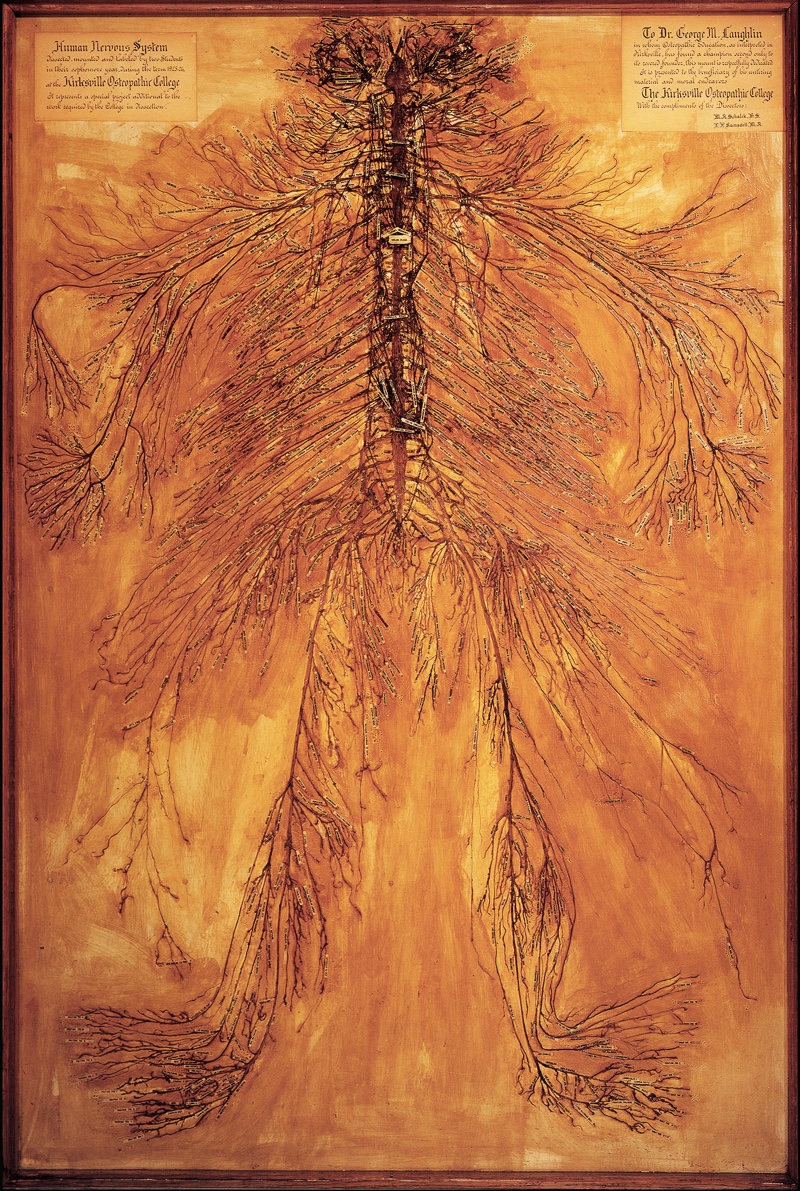

In the fall of 1925, two medical students in Kirksville, Missouri, received a cadaver and a challenge. Their assignment: to dissect the body's nervous system, beginning at the base of the brain and working downward, leaving the system in one continuous piece.

Over the following year, the students — M.A. Schalck and L.P. Ramsdell — spent 1,500 hours of their lives completing the painstaking dissection. A viral photo posted on Reddit on Jan. 30 shows the extraordinary fruits of their labor, which remain on permanent display at the Museum of Osteopathic Medicine at A.T. Still University (ATSU) in Kirksville.

"Medical students come into the museum and stare at it in amazement," Jason Haxton, director of the museum, told Live Science. "Sometimes, they'll run in after a test to check their work. People familiar with dissection say this is truly a miracle piece." [Image Gallery: The Oddities of Human Anatomy]

Article continues belowAccording to Haxton, every student in Schalck and Ramsdell's class at the Kirksville College of Osteopathy & Surgery (an institution founded by Dr. Andrew Taylor Still in 1892, now part of ATSU) was required to dissect a human arm. "These two students' dissections were so detailed, and so much better than any other student's, that they were chosen to dissect an entire body," Haxton said.

Schalck and Ramsdell operated downward from the body's brain stem, exposing the spinal cord and cutting through skin, muscle and protective tissue to clear the maze of nerve fibers within.

"After they cleared each nerve, they rolled them in cotton batting soaked in some kind of preservative," Haxton said. (The exact preservative chemicals used are unknown.) "So, as they worked their way down, there was just a mass of little rolls of cotton."

After 1,500 hours of surgery, Schalck and Ramsdell mounted the dissected nervous system on a slab of shellacked wood. They added hundreds of paper labels to the display and exhibited the finished dissection at medical conferences and museums around the country.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Today, Haxton said, Schalck and Ramsdell's nervous system is one of only four such dissections in the world. (He said he excludes nervous systems exhibited by the traveling exposition Body Worlds, which uses chemicals to help extract the fibers.) In 1936, researchers at ATSU dissected a second nervous system and then donated it to the Smithsonian Institution. A third sample is owned by a medical museum in Thailand, Haxton said, and a fourth is on display at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

"The school anatomist [at Drexel] had a cleaning lady named Harriet," Haxton said. "She donated her body at death, and the anatomist wanted to do something absolutely fantastic. So, in 1888, he dissected her."

As for the person whose body ended up on Schalck and Ramsdell's operating table, nothing is known. Whoever it was likely died in prison or in a poor house, Haxton said, as those were the main state-approved sources of medical cadavers at the time.

Whoever this long-departed Missourian may have been, though, this much is clear: He or she left behind what is now one of the most valuable nervous systems in the world. About 10 years ago, Haxton said, the exhibit was valued at $1 million.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus