Runners' Back Pain Starts Deep, 3D Models Show

Motion-capture technology has revealed that the source of runners' back pain lies deeper than expected, according to a new study.

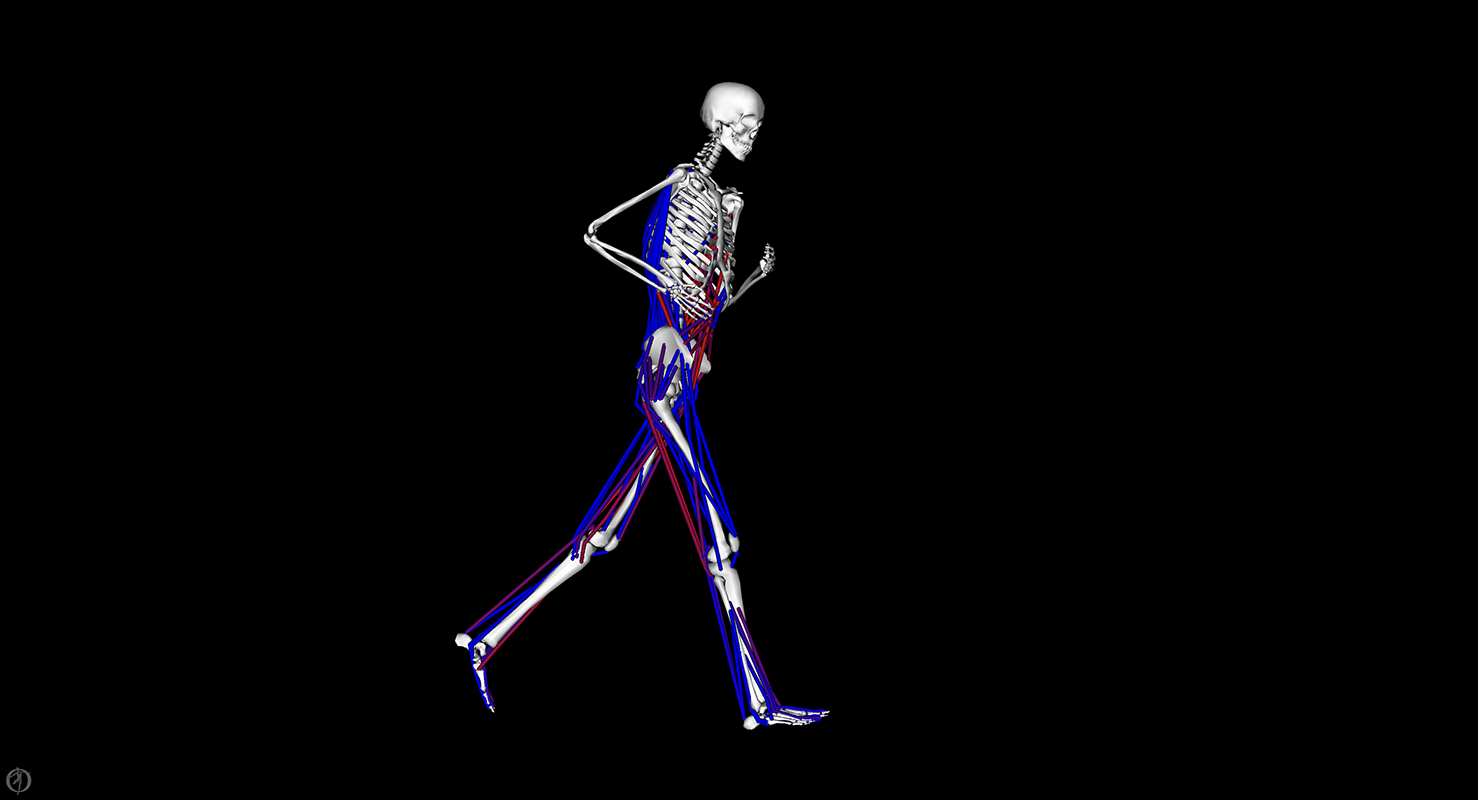

Scientists collected data using a motion-capture system and pressure-sensitive plates as participants ran around a track; the researchers then used the findings to 3D-model bones and muscles in a moving human body.

The models showed the different muscle groups at work during endurance running. The scientists learned that much of the back-supporting burden was carried by muscles in the body's deep core, rather than by the surface abdominal muscles that core-strengthening workouts typically target, according to the study. This could explain why some runners experience back pain even though they perform exercises thought to build core strength, the study authors said. [Lower Back Pain: Causes, Relief and Treatment]

Prior to this study, very little was known about the causes of chronic and recurring back pain in runners, said study co-author Ajit Chaudhari.

Chaudhari, an associate professor of physical therapy, biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering and orthopedic surgery at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, explained that most of the research on running-related injuries focuses on the lower extremities.

For example, "to understand knee injuries better, our focus has always been to look at what's happening in the knee," Chaudhari told Live Science. However, he suggested that by homing in too closely on specific parts of the leg, scientists could be neglecting the bigger picture about how runners get hurt.

"What are we missing about how [the] whole body moves?" he said. "Maybe it is the core. Because half of your body weight is in your upper body, how you control your core affects how you control that whole big mass up on top." That insight led the researchers to consider looking at what was happening in the core "in a more systematic, scientific way," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Building the models

The scientists fitted eight participants with reflective markers on their upper and lower bodies, then used motion capture to record the subjects as they jogged laps around the laboratory. Meanwhile, plates underfoot recorded the magnitude and direction of force as the runners pushed off against the ground.

Using data collected in this way, the researchers constructed 3D models of the runners' skeletons and muscles, estimating how muscle groups would perform for maximum efficiency. The researchers could then manipulate the muscles to conduct "What if?" scenarios, such as "What if deep core muscles were weaker or absent — how would other muscles compensate to achieve the same movement?" Chaudhari said.

By toggling certain muscles on and off to simulate weaker performance, the researchers could detect where stresses would emerge on adjacent muscles and joints, Chaudhari explained.

The scientists discovered that if the deep core muscles weren't doing the hard work of stabilizing a runner's core, surface core muscles would take up the slack. The runner would still be able to perform, but surface core muscles exert forces on the spine that differ from the more stable, deep-core support, which could lead the runner to develop back pain, the study authors reported.

Individual variation

However, there are some drawbacks to using this virtual system to analyze how runners' muscles work, Chaudhari said. The 3D models in the study were generic, and variations in people's bodies — such as longer legs or heavier torsos — could affect the distribution of labor among muscles that kicks in when deep core muscles are weak.

The models were also approximating running that was done as efficiently as possible, but a runner working to optimize another factor, such as stability, could perform differently, Chaudhari added.

Next steps could involve a more long-term study of runners, to see if those with weak deep cores do, in fact, go on to develop low back pain,"or if an exercise program that focuses on the deep core reduces the incidence of low back pain," Chaudhari told Live Science.

"And then, other steps would be trying to identify those exercises — we have some guesses, but we don't really know which exercises will be best for the deep core in which people," he said.

The findings were published online Dec. 6 in the Journal of Biomechanics.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus