10 Times Science Proved the World Is Amazing in 2017

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An Amazing World

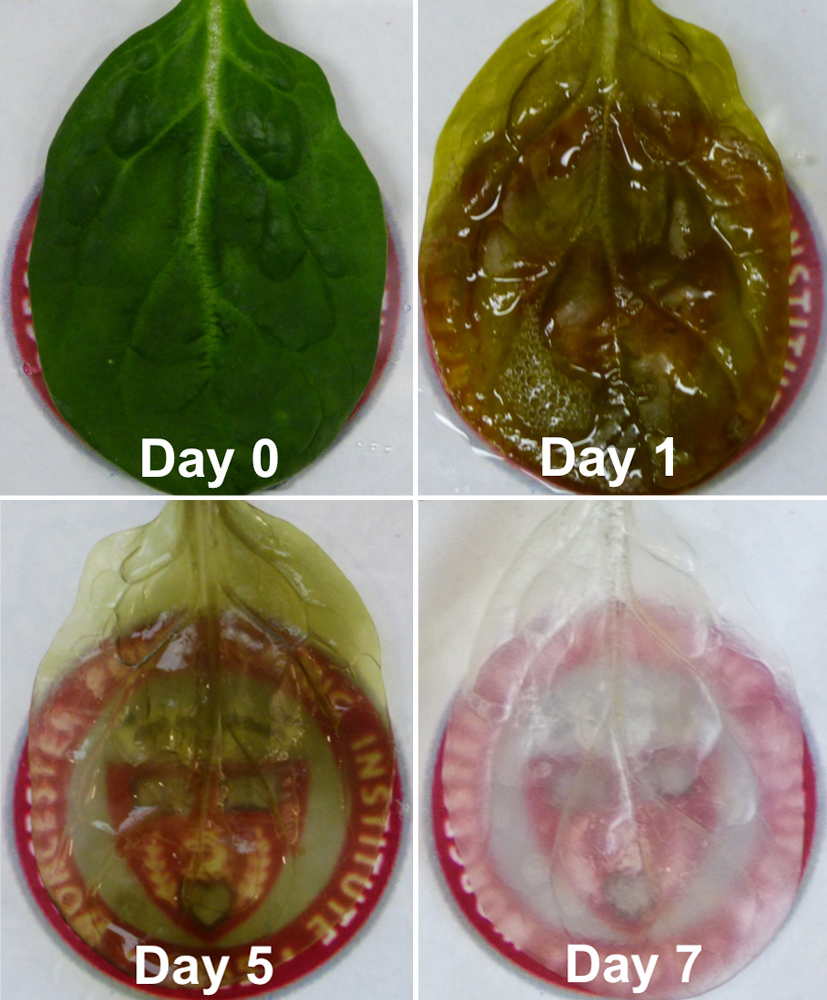

A spinach leaf, pumping with human heart cells. The world's driest desert, overflowing with vibrant wildflowers. An ape with impeccable social skills.

Let's face it: the planet is an odd, amazing place, whether or not you take the time to notice it. In the spirit of celebration, here are 10 offbeat and uplifting stories that you may have missed in 2017, a year of big discoveries (such as a hidden ecosystem under Antarctica's shifting glaciers) and small (a microscopic water bear's first hours of life).

'Hippie chimps' are even more awesome

Bonobos are one of mankind’s closest living primate relatives, but they may have already surpassed humans when it comes to manners.

Sometimes referred to as 'hippie chimps,' bonobos are known for being peaceful, passive and altruistic in their social interactions. Now researchers can add "right neighborly" to the hippie chimp’s profile: in a study published in November, individual bonobos reliably pulled a lever to help other bonobos obtain a food reward, even if the two chimps didn’t know each other. What’s more, bonobos proved eager to lend a helping hand to a stranger without even being asked.

What does all this mean? Extending trust to strangers — a behavior known as xenophilia — likely poses an evolutionary advantage to social primates such as bonobos (and humans), the researchers said. When a female bonobo reaches adulthood, for example, she leaves the social group of her youth to strike up new relationships with female mentors and male mates from other cliques. The ability to make a good first impression can be instrumental to her survival.

A thriving ‘Octlantis’ discovered underwater

An exciting discovery near Australia’s Jervis Bay has all the makings of perfect reality TV: 10 strangers, each one solitary and standoffish, thrust into close quarters to collaborate, quarrel, and (eventually) copulate. Also, in this case, they are all octopuses.

Researchers call it "Octlantis": a thriving cephalopod community where, over the course of 8 days, a group of 10 to 15 octopuses were spotted engaging in "complex social interactions", according to a study published in September. The diverse group of cephalopods foraged together, squabbled over territory and even mated as they shared a small network of close-quarters dens carved into a rocky outcrop off Australia’s east coast.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This extended display of octo-society overturns some serious stereotypes about cephalopods. Octopuses are largely considered to be antisocial loners, researchers said, with some species even finding ways to mate without touching one another. Perhaps there is something in the water in Jervis Bay; in 2009, a similar community dubbed "Octopolis" was found just a few hundred yards away.

A crystal fog over Canada

At 1:30 a.m. on Jan. 6, Timmy Joe Elzinga looked out his window in northern Ontario, Canada and saw a dazzling sight. Towers of shimmering, multicolored light seemed to stab right up out of the snow and stretch into the heavens. Elzinga thought he was witnessing the northern lights, but when he drove to the top of a nearby hill for a better vantage, the lights all but disappeared. What was going on?

These twinkling phenomena, as Elzinga later learned, are called "light pillars" or "crystal fog." Light pillars form on cold nights, according to NASA, when ice crystals that normally reside high up in the atmosphere freeze prematurely and come fluttering down to the ground. When the crystals reflect light from traffic signals, street lamps or other bits of civilization, the result can be a multicolored display of airborne luminescence.

Cosmic coincidence or not, it's understandable why light pillars are often reported as UFO sightings.

A hedgehog with 'balloon syndrome', rescued by vets

Romain Pizzi probably didn’t go into veterinary medicine for the express purpose of "deflating" wild hedgehogs puffed-up with too much air, but life is full of curveballs.

In July, Pizzi, a specialist wildlife veterinary surgeon at the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Scottish SPCA), responded to an unusual call. A wild hedgehog (later named Zepplin by its rescuers) was discovered on the roadside, alarmingly puffed-up to the size of a beach ball. Zepplin suffered from a rare hedgehog affliction known as “balloon syndrome," likely caused by blunt trauma (possibly from a vehicle strike) that led to a tear in his lung tissue. Every time Zepplin inhaled, a bit of air leaked from his lung into his body cavity, slowly inflating his entire body. Pizzi estimated it probably took between 12 and 48 hours for Zepplin to inflate to the state he was found in. While not fatal, balloon syndrome would likely prevent Zepplin from rolling up in self-defense, making him an easy target for predators.

Fortunately, Pizzi and his colleagues were able to "deflate" Zepplin back to his normal size by making a series of small cuts in his skin so the trapped air could escape. They treated Zepplin with antibiotics and kept a close watch on him while his lungs healed.

Human heart tissue grown from spinach leaves

In the year's best news for Popeye, it seems the sailor man's favorite vegetable could one day help replace his actual heart after one too many bouts with Bluto. In several experiments, scientists grew beating human heart cells on spinach leaves by perfusing the leaves with a detergent solution that stripped away their plant cells. The proof-of-concept study suggested that one day spinach leaves could be used to grow layers healthy heart muscle to help treat heart attack patients, the researchers said.

What makes spinach leaves such a good scaffold for growing cells? Researchers say it's the cellulose structure that remains behind after the plant cells have been stripped away. "Cellulose is biocompatible [and] has been used in a wide variety of regenerative medicine applications, such as cartilage tissue engineering, bone tissue engineering and wound healing," the researchers wrote in the study. The team even thinks they could deliver blood and oxygen to developing tissues by pouring liquid through the spinach leaves' veins. Keep your eyes (or, in Popeye's case, eye) on this developing research.

Insight into the life of a baby tardigrade

Sounds cute, right? And surprisingly — for a microscopic, 8-legged creature that can withstand freezing, boiling, intense radiation and the cold vacuum of space — it is cute. Tardigrades, also known as water bears or moss piglets for their tendency to live in or near wet environments, are some of nature's most resilient creatures. Despite measuring less than a millimeter (0.04 inches) in length, an individual tardigrade can survive 30 years without eating by curling up into a death-like state of suspended animation known as cryptobiosis, researchers at the University of Oxford have said. But what do the first few hours of a tardigrade's potentially-long life look like?

Stunning new images by photographer Vladimir Gross give us a glimpse. Using a scanning electron microscope, Gross caught footage of newborn tardigrades just before they emerged from their eggs. (Gross snagged runner-up in the 2017 Royal Society Publishing Photography Competition's Microimaging category.) At about 50 hours old, tardigrade embryos like this one have already developed most of their organs, limbs and mouthparts. When the baby water bear is ready, it will gnaw a hole in its egg and wriggle out into the world to find its first meal. For water bears, there is no childhood: they emerge from their eggs small, but fully formed.

The world's driest desert, covered in flowers

Look up photos of Chile's Atacama Desert on a normal day, and you'll see hundreds of miles of empty, cracking Earth nestled between craggy, rust-colored hills. Atacama is considered the driest nonpolar desert in the world, and typically receives 0.6 inches (15 millimeters) of rain a year. But when an unexpectedly strong rainfall hits the region, as it did this August, a different picture bursts into view: thousands of multicolored wildflowers, blooming as far as the eye can see.

It's called a "super bloom." Once every five to seven years, rains from the El Niño climate cycle sweep off the Pacific Ocean and douse the desert, allowing millions of dormant wildflower seeds to take root and grow. While the Atacama is sparsely populated, rare blooms like these draw thousands of tourists to witness the otherworldly explosion of red, yellow, orange, purple and white blossoms opening across the desert's 600-mile plateau. There's a reason why the locals nickname the driest desert on Earth the "desierto florido" (Spanish for the "flowering desert.")

A spider's world-changing diet

A spider is more than just a pretty face. Arachnids are well known to hunt and eat a lot of insects people don't want around, including disease-spreading flies and mosquitoes. It's hard to define spiders' impact on the environment, but a new study published in the journal The Science of Nature this year took its best shot. Each year, all the world's spiders consume somewhere between 440 million and 880 million tons of insects, the researchers found.

That sounds like a lot of dead bugs — and it is. According to the study authors, the spider's global diet rivals (or perhaps dwarfs) the 440 million U.S. tons (400 million metric tons) of meat and fish all the humans in world eat each year. The researchers determined these numbers by first calculating how much spider tonnage is out there in the world, borrowing some data from previous arachnid studies. They determined there are about 27 million U.S. tons (25 million metric tons) of spider biomass crawling around the planet — around 131 spiders per every square meter of land (about the size of a single mattress). From there, they determined the food needs per spider based on each spider's mass, arriving at the range above.

So be sure to thank the next spider you see: without them, the world would be a whole lot buggier.

A 12th Dead Sea Scroll cave found in Israel

In the Judean Desert east of Jerusalem, secrets of the past wait in ancient caves. Between 1947 and 1956, the Dead Sea Scrolls — a collection of Hebrew Bible texts, community rules, calendars, and other writings dating between roughly 200 B.C. and A.D. 70 — were discovered in 11 caves in what is now the West Bank. Earlier this year, archaeologists uncovered a 12th.

While the cave did not contain any new Dead Sea documents, the researchers were confidant this was not always the case. A blank scroll, the husks of broken ceramic jars and leather wrappings all indicated that the cave had once contained a collection of ancient scrolls, but had likely been picked-over by antiquities thieves in the mid-20th century. Despite being beaten to this particular buried treasure, archaeologists see the finding as proof that there are far more than 12 Dead Sea caves waiting in the Judean cliffsides.

"The important discovery of another scroll cave attests to the fact that a lot of work remains to be done in the Judean Desert, and finds of huge importance are still waiting to be discovered," Israel Hasson, director-general of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said in a statement.

A new ecosystem under Antarctic ice

There is a hidden world beneath the ice shelves of Antarctica, completely devoid of sunlight and largely isolated from open ocean currents. Scientists know little about this environment, but may soon get a chance to observe it up close. As the iceberg known as A-68 splits away from Antarctica's Larsen C ice shelf and drifts into the Weddell Sea, it will eventually expose 2,240 square miles (5,800 square kilometers) of seafloor that has been buried under the ice for up to 120,000 years, according to scientists with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

According to a study published online in the journal Nature in September, researchers from around the world are gearing up to visit the newly-revealed ecosystem as soon as early 2018, before the seafloor's sudden exposure to sunlight drastically alters its biodiversity. This is not the first time scientists have observed the mysterious world beneath the ice sheets, however, previous expeditions reached the newly-exposed ecosystems between 5 and 12 years after the initial iceberg separations.

If researchers can reach the new Larsen C site quickly, they will earn an unprecedented view of an ecosystem untouched for more than 100,000 years — and greater insight into how environments like this one change when suddenly exposed to the sunlight, an occurrence that is expected to happen more and more as Antarctic ice melts.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus