'Vegetarian' Dinos Made Exception for Shellfish, Poop Study Shows

Certain giant, herbivorous dinosaurs didn't eat just plants — they also chowed down on rotten logs harboring shellfish, a new study finds.

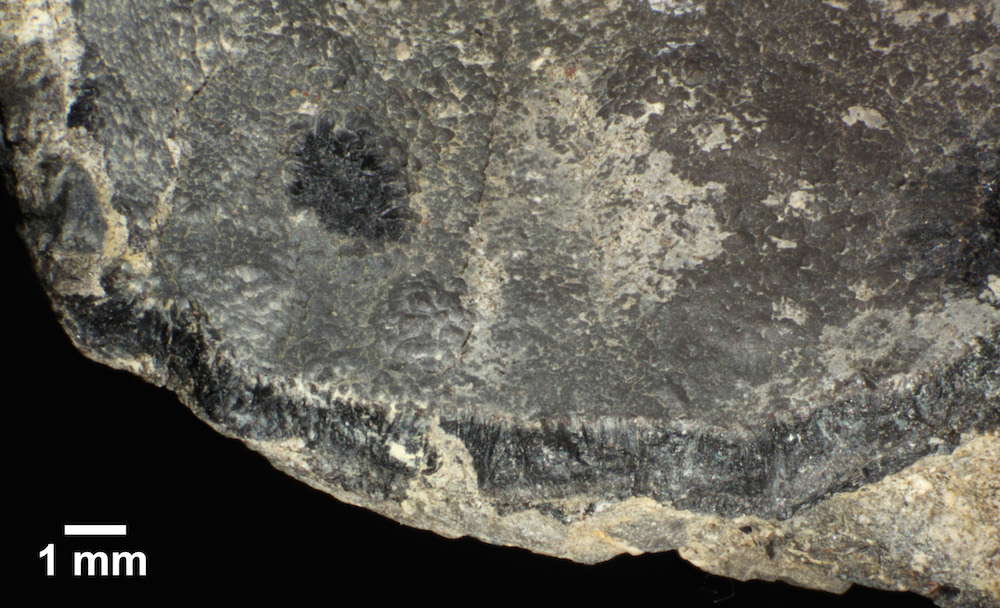

Researchers made this startling dietary discovery after examining 10 different specimens of fossilized dinosaur dung, known as coprolites, from the Kaiparowits Formation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah.

"If we had found just one coprolite with crustacean pieces in it, that would have been interesting," said study lead researcher Karen Chin, an associate professor and a curator of paleontology at the University of Colorado Boulder. "But the fact that we found coprolites that spread out over at least 20 kilometers [12 miles] at different stratigraphic levels — that really strengthens our evidence for this being a behavior that these dinosaurs engaged in." [Image Gallery: Parasite Eggs Lurk in Fossilized Shark Poop]

The coprolites with the crustacean shells — including what might be a crab shell — are filled with the remains of rotted wood, and date to between 76 million and 74 million years ago. Rotten wood is "kind of an unusual diet," Chin said, "but when you rot the wood, it increases the availability of cellulose [fiber] in the wood. Ranchers down in Chile have been known to open up rotted logs and their cattle just gravitate toward them and start feeding on the rotted wood."

It's possible that the dinosaurs ate the rotted wood to get fiber, as well as fungus and insects living in the rotted logs, Chin said. Of course, by eating the logs, the dinosaurs were also swallowing the crustaceans living in the damp, decomposing logs, but it's unclear whether the dinosaurs were purposefully or unintentionally eating the crustaceans, Chin said.

However, given that crustaceans are a good source of protein and calcium — a mineral needed during eggshell production — perhaps female dinosaurs were intentionally eating the crustaceans in preparation for laying eggs, a behavior also seen in breeding birds, Chin said.

It's unclear what type of Late Cretaceous dinosaur left the poop, but the formation was filled with the fossils of duck-billed dinosaurs, or hadrosaurs. Those dinosaurs' duck bills had teeth that were powerful enough to grind rotted logs, and so the droppings likely came from Gryposaurus, a 27-foot-long (8 meters) duck-billed dinosaur found at the site, Chin said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What's more, the researchers wanted to make sure that the thick crustaceans were digested, as opposed to wandering into the dinosaur feces after the fact. But the evidence is fairly clear that the dinosaurs ingested the critters, Chin said.

"If the crustacean had just wandered in there, even if it had been stepped on by a dinosaur, it would mostly be together," Chin said. "These pieces of crab are scattered throughout the coprolites."

Chin noted that this is the first example on record of "fairly large" crustacean fragments in dinosaur coprolites. There are dinosaur coprolites from India containing teeny, tiny ostracods — crustaceans also known as seed shrimp — but these ostracods are just 0.04 inches to 0.08 inches (1 to 2 millimeters) long, while the fragments from this study are as large as 1.1 inches (3 centimeters) across, Chin said.

The study "kind of turns our stereotype of plant-eating dinosaurs on its head," said Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland who was not involved in the research.

"When you cut into the coprolite of a plant-eating dinosaur, you expect to find only plants, so the crustaceans inside are a real surprise," Brusatte said.

Still, despite its shock value, the finding is not too unexpected, Brusatte said. "A lot of herbivores today also ingest animals, sometimes accidentally or sometimes to supplement their diet. These dinosaurs were no different."

The study was published online today (Sept. 21) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus