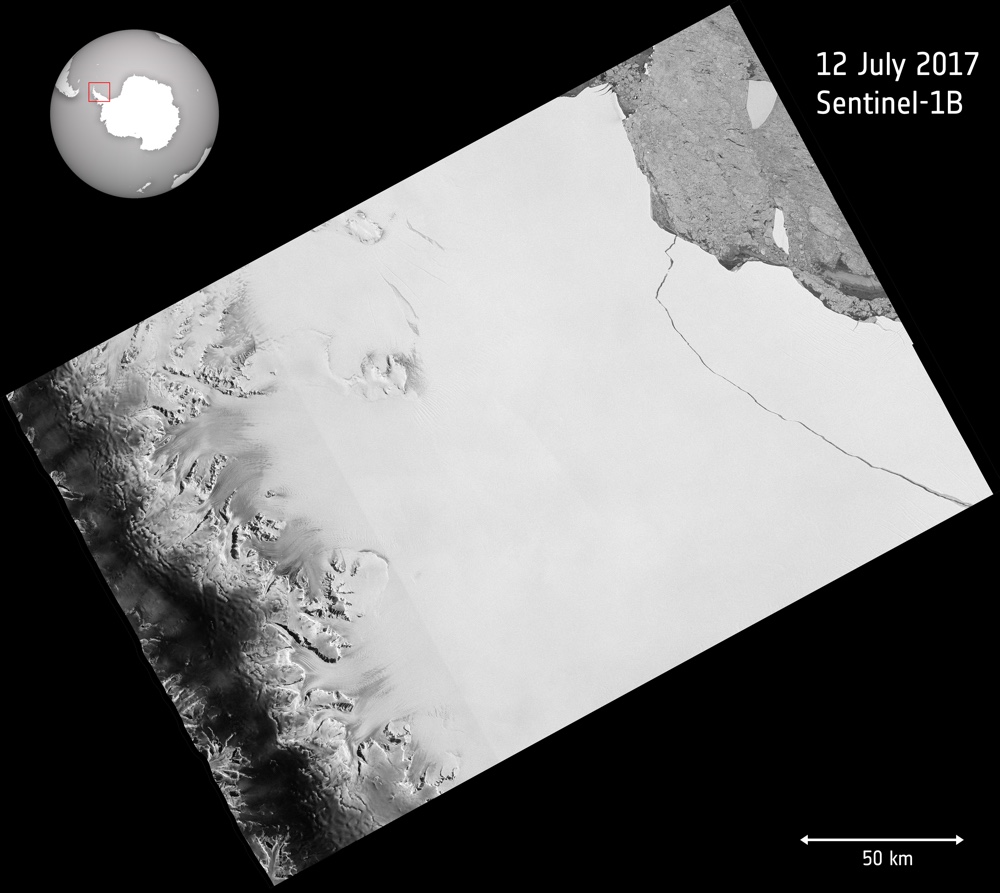

Trillion-Ton Iceberg Breaks Off Antarctica

One of the largest icebergs ever recorded, packing about a trillion tons of ice or enough to fill up two Lake Eries, has just split off from Antarctica, in a much anticipated, though not celebrated, calving event.

A section of the Larsen C ice shelf with an area of 2,240 square miles (5,800 square kilometers) finally broke away some time between July 10 and today (July 12), scientists with the U.K.-based MIDAS Project, an Antarctic research group, reported today.

Scientists discovered the birth of this iceberg in data collected by an instrument aboard NASA's Aqua satellite, called MODIS, which takes thermal infrared images. [In Photos: Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf Through Time]

The iceberg was expected, though scientists didn't know when the crack in the ice sheet would finally release the floating chunk. The rift in the Larsen C ice shelf — the fourth-largest shelf in Antarctica — has been around for decades, but it wasn't until November 2016 that satellite measurements revealed it had grown to more than 300 feet (91 m) in width and 70 miles (112 km) in length. The most recent measurements from this summer put the rift at 124 miles (200 km) long, with the now-calved iceberg hanging on by a thread; just 3 miles (5 km) of ice connected it with the rest of the ice shelf.

Even though the towering berg weighs more than 1.1 trillion tons (1 trillion metric tons), it won't have a direct impact on sea-level rise. That's because the ice was already floating on the sea. Even so, when an iceberg like this one calves, it can speed up the collapse of the rest of the ice shelf — the new iceberg reduced the area of the Larsen C ice shelf by 12 percent. Also, the ice shelf serves as a barrier to the land-based glacier that feeds the ice shelf; as that barrier diminishes, there's more of a chance for the ice behind it to collapse into the sea, MIDAS researchers said.

And it's this once-land-based ice that would impact sea levels, researchers say.

"Although this is a natural event, and we're not aware of any link to human-induced climate change, this puts the ice shelf in a very vulnerable position," Martin O’Leary, a Swansea University glaciologist and member of the MIDAS project team, said in a statement. "This is the furthest back that the ice front has been in recorded history. We're going to be watching very carefully for signs that the rest of the shelf is becoming unstable."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As for what will happen to this huge chunk of ice, nobody knows at the moment.

"The iceberg is one of the largest recorded and its future progress is difficult to predict," Adrian Luckman of Swansea University, lead investigator of the MIDAS project, said in the statement. "It may remain in one piece, but is more likely to break into fragments. Some of the ice may remain in the area for decades, while parts of the iceberg may drift north into warmer waters."

Editor's Note: This article was updated to clarify when the rift in the ice sheet first showed up.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.