Millions of 'Sea Pickles' Invade Northwest Waters

The waters off the Oregon coast are mysteriously awash with strange, jelly-like creatures that look like translucent slugs, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The waters off the Oregon coast are mysteriously awash with strange, jelly-like creatures that look like translucent slugs, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

These bizarre organisms, called pyrosomes (Pyrosoma atlanticum), began appearing off Oregon's coast in 2015, but in recent months, their numbers have multiplied into the millions, NOAA's Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Newport, Oregon, reported.

P. atlanticum usually live in tropical waters. Even so, they are thriving in the Northwest's typically chilly Pacific Ocean, multiplying to the point of clogging local waters and fishing gear. [Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

For instance, a 5-minute midwater tow with a research net off Oregon's Columbia River in late May captured roughly 60,000 pyrosomes. The scientists who caught them had been looking for a rare fish, and had to spend hours sorting through the pyrosomes until they found their target, they said.

"We have a lot of questions and not many answers," Ric Brodeur, a research biologist at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center, said in a statement. "We're trying to collect as much information as we can to try to understand what is happening and why."

Strange colony

Each pickle-like creature is, in fact, a colony made up of individual zooids that join to create a hollow, tube-like structure that has one closed end and one open end. (A zooid is a small, multicellular organism that makes up part of a colonial animal, and can arise from another zooid by budding or dividing.)

These plankton-eating filter feeders hang out hundreds of feet below the water's surface during the day, and migrate vertically to the surface at nighttime. But little is known about their eating behavior and how that impacts food chains, especially when they show up in large numbers, NOAA officials said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

P. atlanticum are pelagic, meaning they live far from land, in the open ocean. In this case, the pyrosomes are found in high densities from about 40 miles to 200 miles (60 to 320 kilometers) off the Oregon coast, NOAA officials said.

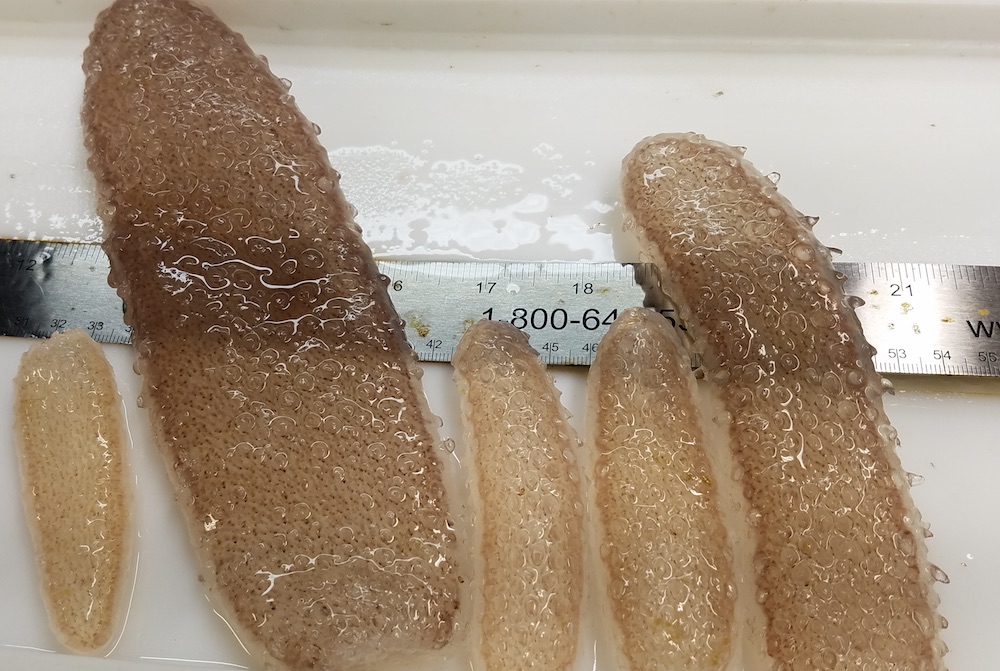

Oregon's pyrosomes range from about 1.5 inches to 2.5 feet (4 to 78 centimeters) long, and researchers have found even larger pyrosomes farther off the coast, NOAA reported.

"At first, we didn't know what to make of these odd creatures coming up in our nets, but as we headed north and farther off shore, we started to get more and more," Hilarie Sorensen, a University of Oregon graduate student, said in the statement. "We began counting and measuring them to try to get a better understanding of their size and distribution related to the local environmental conditions."

Pyrosome predators include certain fish, dolphins and whales, the agency added.

It would take quite a few of these predators to make a dent in this pyrosome boom. The creatures' population expansion is also taking over waters off northern California, Washington and southeast Alaska. Researchers plan to study them further to see what factors led to the creatures' sudden rise, NOAA officials said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus