Skeleton of Teen Girl Yields Central America's Oldest Cancer Case

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists have uncovered another layer of intrigue in the ritual burial of a teenage girl in western Panama. A new analysis of her 700-year-old skeleton shows that she had a tumor in her arm. It could be the oldest known case of cancer discovered in Central America.

The remains of the girl, who died between the ages of 14 and 16, were originally discovered in 1970, buried in an ancient trash heap at a settlement called Cerro Brujo, or Witch Hill. But her body wasn't tossed callously into the town dump. Archaeologists think she died around the year A.D. 1300, and by that time, Witch Hill had already been abandoned for 150 years, so perhaps this burial site was chosen because she had ancestral ties to the settlement.

"Based on the fact that the body was tightly wrapped in the fetal position and buried facedown with two clay pots and a shell trumpet like those still used by indigenous Ngäbe people in this area today, we consider this a ritual burial," Nicole Smith-Guzmán, a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, said in a statement. [16 Oddest Medical Cases]

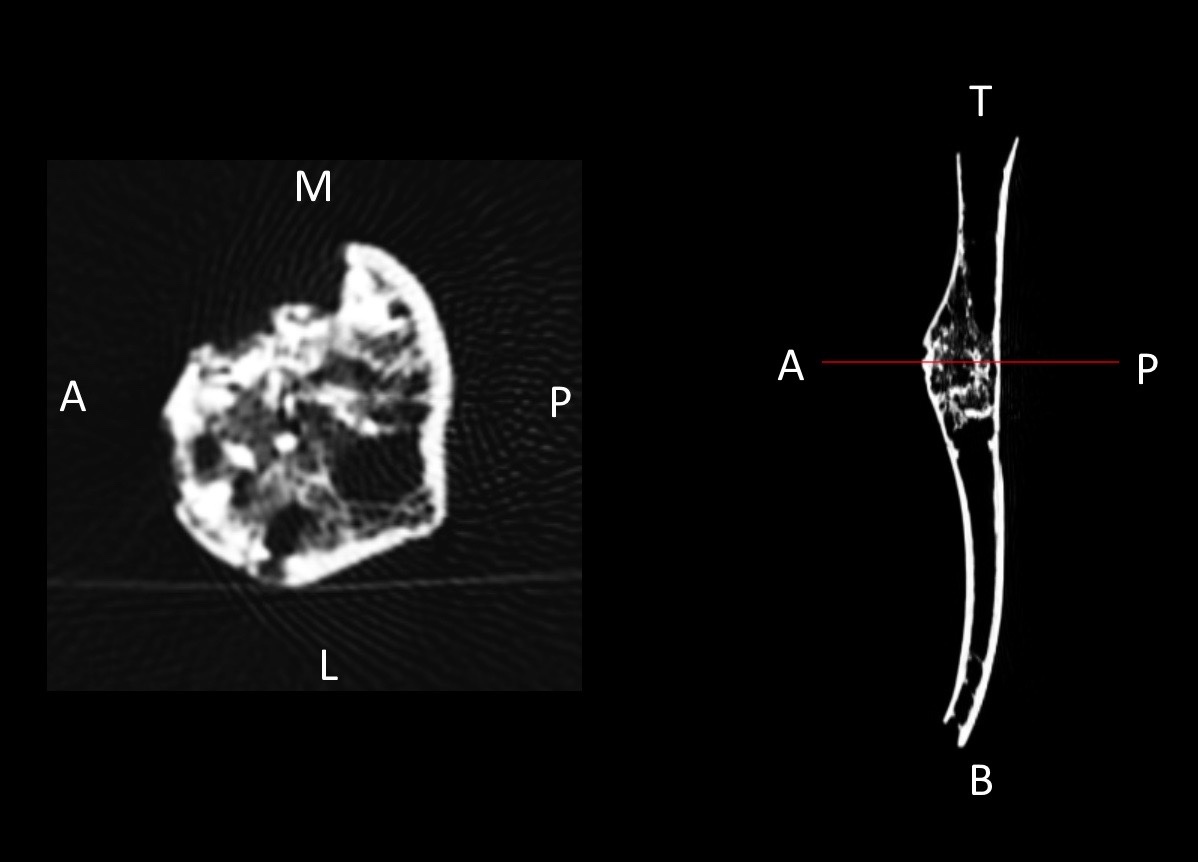

Smith-Guzmán, a bioarchaeologist, was looking for marks of health problems on the girl's remains. She identified the signs of cancer in the right upper arm, and computed tomography (CT) scans confirmed that there were indeed lesions inside the bone.

In their new paper, published online May 26 in the International Journal of Paleopathology, Smith-Guzmán and her colleagues concluded that the most likely explanation is osteosarcoma, the most common form of malignant bone tumor in children. But without soft tissues to make a diagnosis as a doctor would today, they couldn't rule out the possibility of other types of cancer, like Ewing sarcoma (a type of tumor that forms in bone or soft tissue).

In recent decades, bioarchaeologists have documented cancer cases from ancient skeletons across the world. (They've even found a case of osteosarcoma in a human ancestor's toe bone, nearly 2 million years old, in South Africa.) But there haven't been many examples from the region around Witch Hill.

"As far as we know, this is the first case of cancer in ancient human remains reported from Central America," Smith-Guzmán said, adding that what makes this find even rarer is that it's a case of adolescent cancer. "Most of the published cases of these cancers in the past were from adults — probably due to the poor preservation of non-adult skeletal remains," she added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The girl probably would have experienced pain as the tumor grew and caused her upper arm to swell in size. Based on the practices of today's indigenous Ngäbe people, the researchers also think it's likely that the girl would have been brought to a shaman for treatment.

"The Ngäbe believe that sickness is caused by a disruption of the balance between the natural and supernatural worlds, in which a malevolent spirit enters the body while the afflicted is dreaming to steal the soul," Smith-Guzmán and her colleagues wrote in the paper.

Next, Smith-Guzmán plans to use ancient DNA analysis to learn about the girl's ancestry and the type of cancer that afflicted her.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus