Death by Octopus: This Dolphin Bit Off More Than He Could Chew

A dolphin named Gilligan might have bitten off more than he could chew when gulping down an octopus.

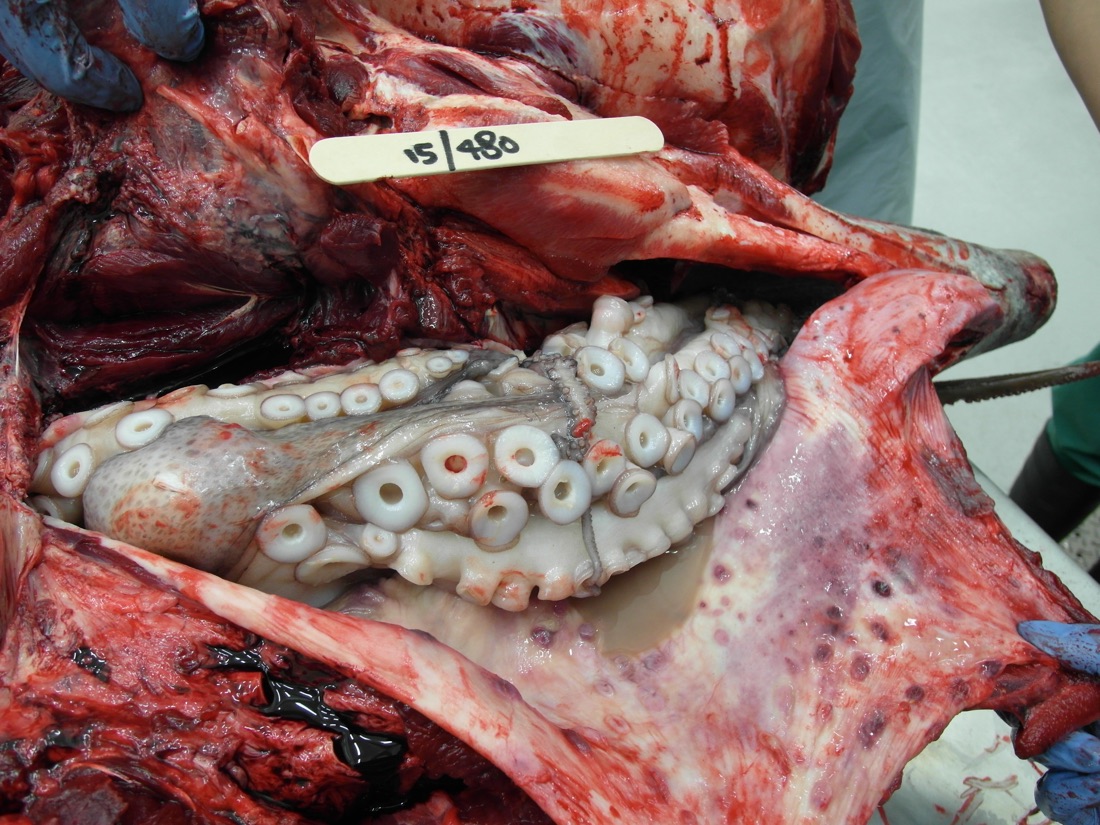

The corpse of the dolphin, with the dead cephalopod's sucker-lined arms hanging out of its mouth, washed up on Stratham Beach in Western Australia on Aug. 30, 2015. Now, after a thorough study of the hungry dolphin's body, researchers can now confirm the cause of death.

"The octopus obstructed his airway, resulting in his suffocation," Nahiid Stephens, a lecturer in pathology at Murdoch University in Western Australia, told Live Science in an email. "He choked, in a nutshell." [Beastly Feasts: Amazing Photos of Animals and Their Prey]

How to eat an octopus

A year-round population of about 60 Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) is known to live off the coast of the busy port city of Bunbury. And it's not uncommon to find octopus on these dolphins' menu. However, 60 percent of these dolphins that had been seen chowing down on octopus were female.

And this was a male that had never been observed eating the eight-armed cephalopod: When the scientists discovered the octopus-eating dolphin, they looked through photos from past surveys in the area. They found that the dolphin was a male dubbed Gilligan, who was first spotted as an adult in 2007 and thus was likely more than 20 years old when it died, the scientists said.

Typically, dolphins are meticulous when they consume octopus.

"Dolphins either kill or stun octopus before swallowing them, by using complex handling techniques of shaking and tossing," Stephens told Live Science. "This octopus was either still alive, insufficiently stunned, or it could have been dead," because even after death, octopus arms and suckers are still functional for some time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cause of death

After examining Gilligan's body, Stephens and her colleagues found that the cephalopod suckers were still adhered to the inside of the lining of the dolphin's tongue and throat.

They also found that the dolphin's larynx was squished, obstructed and unable to link up with the nasal passage. As such, the dolphin was likely unable to exhale, the researchers said. When the team removed the obstruction, the overinflated lungs deflated, they said.

One of the octopus's arms extended down the dolphin's esophagus and into the entrance of the first gastric compartment. (Dolphins' stomachs have three chambers.)

"The octopus' mantle (including eyes and brain) was completely detached and within the first compartment, leaving the 'crown' of arms intact," the researchers wrote in their study, which was published online May 22 in the journal Marine Mammal Science.

This was no puny meal for the dolphin. The researchers identified the cephalopod as a benthic inshore Maori octopus (Macroctopus maorum) that weighed 4.6 lbs. (2.1 kilograms) and extended 4.3 feet (1.3 m) at its widest arm span. The species, which is the world's third-largest octopod, can reach a whopping 26 lbs. (12 kg) and have a maximum arm span of more than 9.8 feet (3 meters), the researchers report in their study.

Dolphins are constantly swimming, which requires substantial energy. Therefore, they need to decide whether the energy required for (and risk involved in) taking down such prey is worth it, the researchers noted.

"Assuming an octopus carcass is sufficiently processed to render its arms into small enough fragments such that they and their suckers can be effectively and safely swallowed, their consumption must generally be a risk worth taking, although it did not play out well in this individual's case," the researchers concluded.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.