Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have spotted water vapor and evidence of exotic clouds in the atmosphere of an alien planet known as HAT-P-26b.

The researchers also determined that HAT-P-26b's atmosphere is dominated by hydrogen and helium to a much greater degree than that of Neptune or Uranus, the alien world's closest counterparts in our own solar system in terms of mass.

"This exciting new discovery shows that there is a lot more diversity in the atmospheres of these exoplanets than we have previously thought," David Sing, an astrophysics professor at the University of Exeter in England, said in a statement. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets] "This 'warm Neptune' is a much smaller planet than those we have been able to characterize in depth, so this new discovery about its atmosphere feels like a big breakthrough in our pursuit to learn more about how solar systems are formed, and how it compares to our own," added Sing, the co-leader of a new study about HAT-P-26b that was published online today (May 11) in the journal Science.

Water and alien clouds

HAT-P-26b lies about 430 light-years away from Earth. The alien planet circles very close to its host star, completing one orbit every 4.2 Earth days. This proximity suggests that HAT-P-26b is tidally locked, showing the same face to its star at all times, said Hannah Wakeford, co-leader of the new study and a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

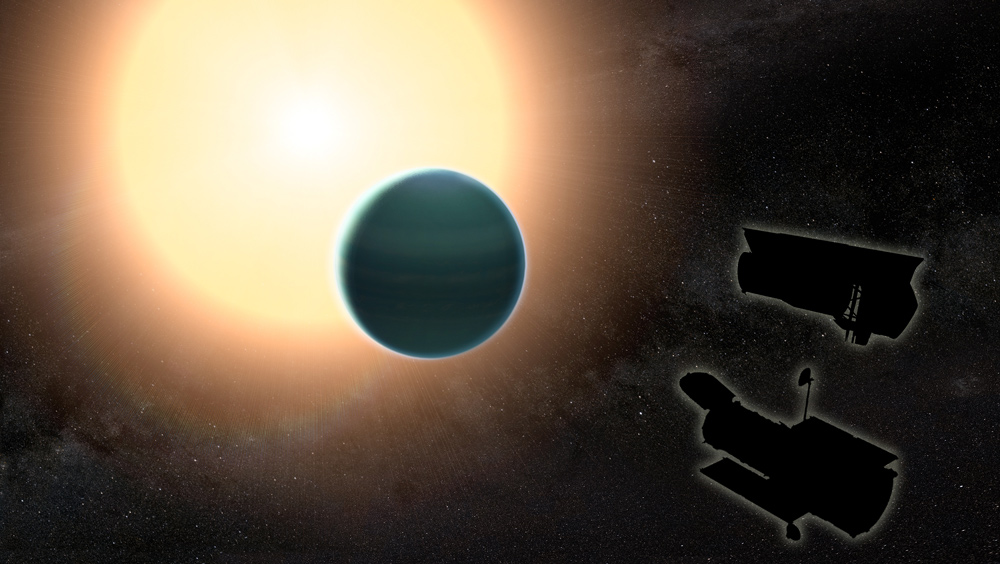

Sing, Wakeford and their colleagues analyzed observations made by NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes when HAT-P-26b crossed its parent star's face from the telescopes' perspectives. The planet's atmosphere filtered out certain wavelengths of starlight during these "transits," allowing the study team to identify some of the molecules swirling in HAT-P-26b's air.

One such molecule is water.

"For this mass range, this is the strongest water-absorption feature that we have ever measured," Wakeford told Space.com.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

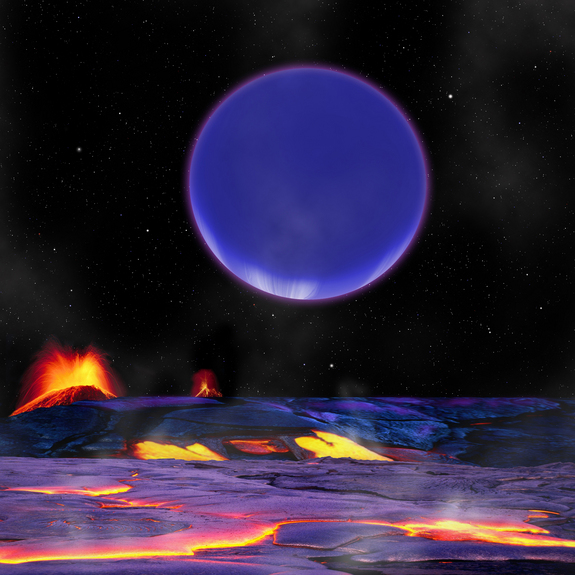

The data also indicate that clouds scud across HAT-P-26b's skies, but relatively deep in the atmosphere; they do not block much of the water-absorption signal, Wakeford said. These clouds are probably made of disodium sulfide, not water vapor like those of Earth, she added.

"This would be a very alien sky that you would be looking at," Wakeford said. "These clouds would cause scattering in all of the colors, so you'd get a kind of scattery, washed-out, gray sky, which is interesting, if you were looking through these clouds."

Ultrabright light streaming from the nearby star would bombard an observer above the clouds, she added. "There's nothing there to really help stop that sunlight from reaching you."

Astronomers have confirmed more than 700 planets beyond our own solar system, and the discoveries keep rolling in. How much do you know about these exotic worlds?

Alien Planet Quiz: Are You an Exoplanet Expert?

Clues about planet formation

Using the transit data, the study team also calculated the "metallicity" of HAT-P-26b's atmosphere — how much of it is made up of elements other than hydrogen and helium. (To an astronomer, anything heavier than helium is a metal.)

In Earth's solar system, metallicity goes down as a planet's mass goes up. For example, Neptune and Uranus both have metallicities about 100 times greater than that of the sun (which is almost entirely hydrogen and helium), whereas the much larger Saturn and Jupiter are just 10 and five times more metallic than the sun, respectively.

But HAT-P-26b does not fit that pattern. Though the exoplanet is about as massive as Neptune, its metallicity is more in line with that of Jupiter, the researchers in the new study found.

This surprising bit of information holds clues about HAT-P-26b's formation and evolution, Wakeford said.

"It suggests that this smaller planet actually formed closer to its star, more like where Jupiter formed," she said. "And we didn't know before that you could form [such] planets in that region. We expected the smaller worlds to be formed further out, where they would accumulate clumps of icy debris and richer heavy elements during the formation in the [protoplanetary] disk." (In these scenarios, planets such as HAT-P-26b migrate inward, toward their stars, after they form.)

Over the last decade or so, NASA's Kepler space telescope and other planet-hunting instruments have revealed a staggering array of alien worlds and solar system architectures. The new study, and others like it, should help researchers better understand the reasons for this variety, Wakeford said.

"This is the first step toward looking at the diversity in the formation process as well," she said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus