White Water: NASA Probes Snow's Effect on Water Resources

No resource on Earth is more precious than water; all life on the planet depends on it to survive. However, only a fraction of Earth's water, a mere 3 percent, is freshwater, and about 70 percent of that freshwater is inaccessible, locked up in glaciers, ice and permanent snow cover.

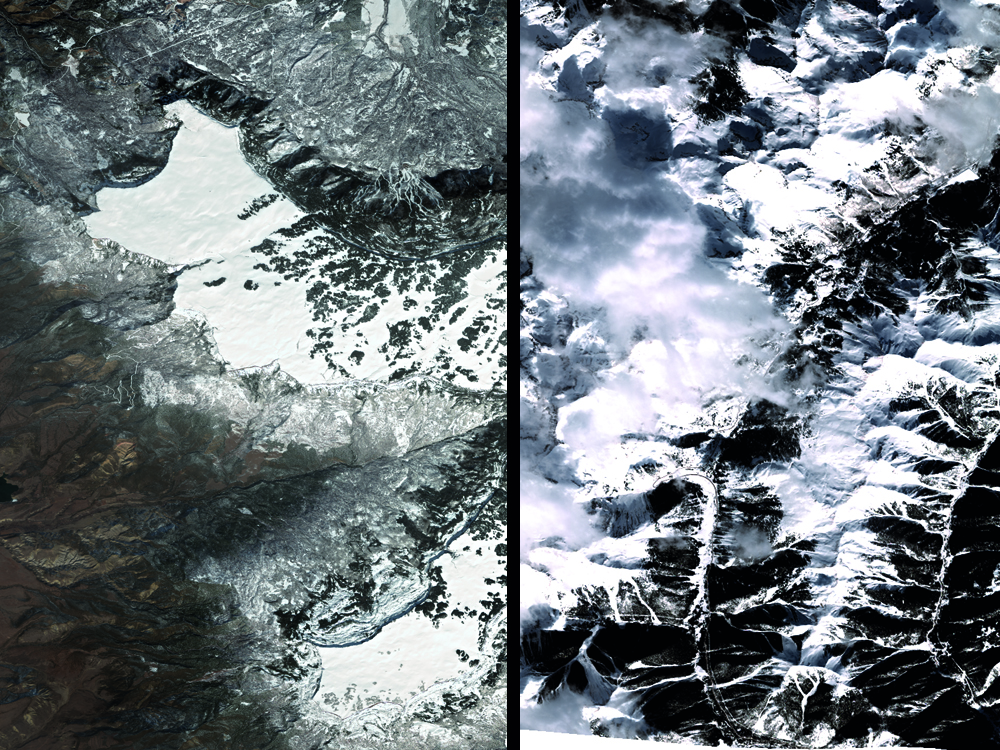

In fact, both seasonal and year-round snowpack are vital parts of Earth's water cycle and its freshwater reserves. Recognizing this, NASA recently launched a new initiative to investigate the planet's snow and the relationship of this snow to readily available liquid water.

SnowEx, a multiyear airborne research campaign led by NASA scientists, seeks to improve methods used to measure snow depth and volume. By testing equipment and techniques for calculating the amount of water contained in snow cover, scientists hope to improve their understanding of how fluctuations in snow accumulation affect water accessibility worldwide — for agriculture, power and drinking, NASA said. [Monitoring Snow Changes: NASA Scientist Dalia Kirschbaum Explains | Video]

NASA experts will collaborate with dozens of scientists from across the U.S., Canada and Europe, said Edward Kim, a SnowEx researcher, in a statement. Kim is also a remote sensing scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

"Our goal is to find and refine the best snow-measuring techniques and [determine] how they could work together," Kim said. "This is the most comprehensive campaign we have ever done on snow."

Because snowpack is typically 40 to 95 percent air, water content is calculated by either measuring the snowpack's mass or establishing its depth and density, according to a NASA report.

A multisensor approach

Satellites have monitored seasonal snow cover from space for decades, but they can't accurately measure the amount of water trapped in snow across different types of snow-covered landscapes, according to NASA. Accurately measuring forest areas is particularly challenging, and prior evaluations are thought to have underestimated water storage in snow by as much as 50 percent, agency officials said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other surveys using remote-scanning technologies also painted an incomplete picture of water storage in snow. Microwave frequencies become "blind" to snow when it's partly melted, and lidar, a scanning method that uses lasers, is unable to penetrate clouds, limiting its usefulness to track snowstorm accumulations.

To overcome these technical limitations, SnowEx will gather its data with multiple sensors, incorporating emerging technologies — such as those that use altitude and gravity sensing — with more established methods like spectroscopy, radar and radio sensing. A total of five aircraft deploying 10 different sensors will allow scientists to adjust scanning options in response to different terrains and different types of snow, NASA representatives said in a statement.

Scientists will also work on the ground at two Colorado sites: Grand Mesa and Senator Beck Basin. Data collected during fieldwork will serve to verify the findings of remote-sensing aircraft, and the results will help to determine SnowEx goals in the coming years — perhaps even informing the future development of satellites capable of detecting snow volume from space, NASA officials said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus