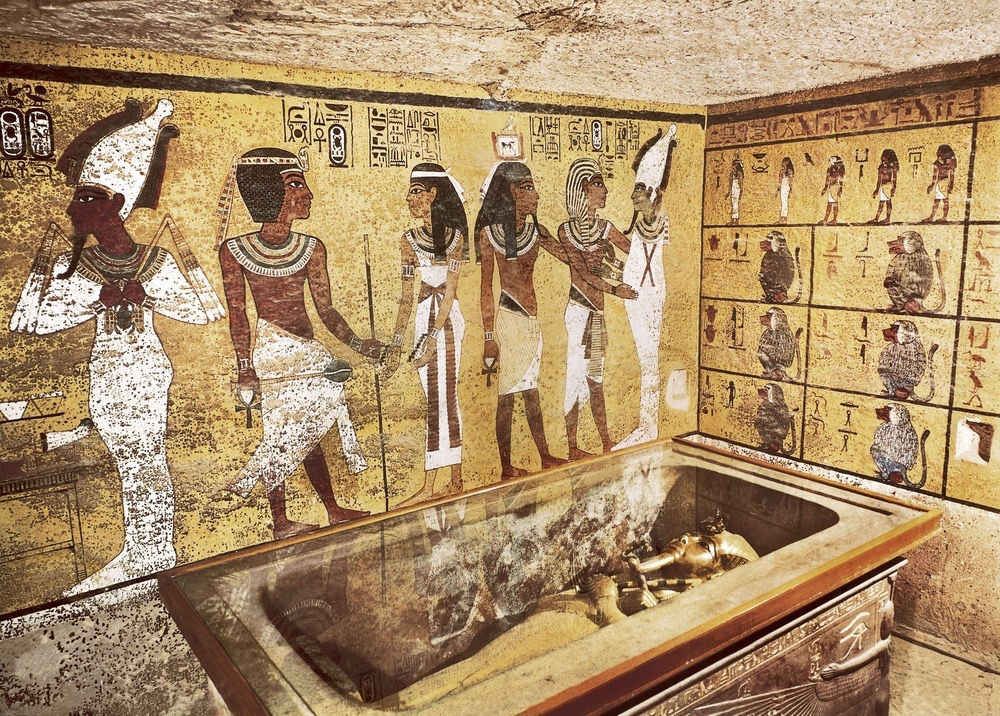

Possible 'Hidden Chamber' in King Tut's Tomb Invites More Secretive Scans

A group of archaeologists has said the tomb of Tutankhamun may hold a hidden chamber containing the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. So far, radar scans have failed to confirm such a chamber.

Now, a physicist plans to lead a team conducting another series of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) scans as a last-ditch effort to find Nefertiti's burial site. In this method, high-frequency radio waves bounce off the ground and off of walls, and the reflected signals can reveal hidden treasures, or empty chambers.This is the third time that this method has been used in Tutankhamun's tomb and it is unclear how the new scans will be different than the others.

The study leader, physics professor Francesco Porcelli at the University of Turin in Italy, told Live Science that he cannot say anything more about the upcoming scans without the approval of Egypt's antiquities ministry. The ministry did not return a message left by Live Science. [See Photos of King Tut's Burial and Radar Scans]

In 2015, Nicholas Reeves, director of the Amarna Royal Tombs Project, proposed the idea that a hidden chamber inside King Tut's tomb contained the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. Ground-penetrating radar scans carried out by radar technologist Hirokatsu Watanabe supposedly showed evidence of two hidden chambers. Reeves published a paper presenting his theory in 2015. He did not return a request for comment from Live Science.

Then, in May 2016, a National Geographic team conducted another set of ground-penetrating radar scans.Those scans showed no hidden chambers in King Tut's tomb. However, the National Geographic Society has barred members of that team from talking publicly about their research, said Dean Goodman, one of the leaders of the National Geographic team.

The team signed a nondisclosure agreement with the society, which can't be waived unless the Egyptian antiquities ministry approves, a spokesperson for the society explained.

While Goodman cannot speak publicly about his team's results, he expressed confidence in the Turin team, saying he knows several of its members well. The "King Tut research is in good hands," he told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Lawrence Conyers, an anthropology professor at the University of Denver who is a leading expert in the use of ground-penetrating radar in archaeology, has criticized the decision of Egyptian authorities to withhold data. He told Live Science that he thinks it is a good idea for the Turin team to do additional scans, but that he hopes Egyptian authorities will allow researchers to access the data, which he said they did not do previously.

"Perhaps this time they will release the data to the GPR community and do a 'peer review' instead of holding it all secret and just releasing 'results' that have no basis in actual data!" wrote Conyers in an email, noting that the National Geographic team data has never been released to scientists.

"I was not privy to the National Geographic dataset, and for some reason they would not let others look at it," he said.

Conyers added that there is no way that archaeologists with expertise in ground-penetrating radar, who are not affiliated with the research, will ever support the idea of a hidden chamber or tomb in Tutankhamun's tomb unless the Egyptian authorities allow scientific data to be released for full scrutiny.

"There is going to be no consensus by anyone knowledgeable on the subject until they do more than hold press conferences," he said.

Other scientists, speaking to Live Science on condition of anonymity, have expressed similar concerns, noting that scientists who have data suggesting no such hidden chamber exists have been barred from speaking publicly. Those who advocate for the hidden tomb's existence have more freedom to talk to the media and write about their findings, these scientists have said.

Egypt's tourism numbers plunged after the 2011 Egyptian revolution, leading to a loss of jobs and tourism revenue in the country, archaeologists familiar with the situation have said. This has led to concerns among scientists that Egyptian authorities are more interested in using the publicity surrounding the scans to help the tourism industry and that authorities do not want data to be published, or publicized, which shows that there is no hidden tomb.

The Egyptian antiquities ministry did not return requests for comment from Live Science at the time this story was published.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.