3D-Printed Micro-Camera Sees with Eagle-Eye Vision

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

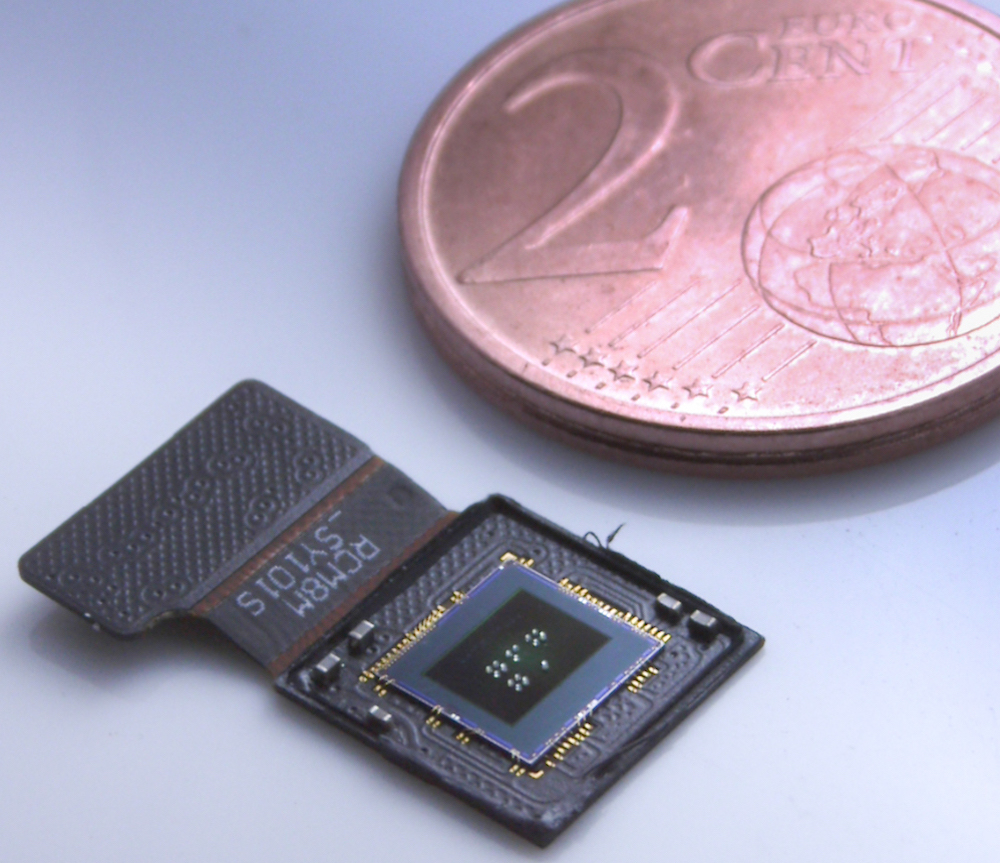

A bird of prey on the hunt must be able to clearly see faraway objects while remaining aware of threats in its peripheral vision. In some cases, that's also true for a drone — even one so small that its eye must fit on the tip of a ballpoint pen. Now, a team of engineers has developed a camera that could provide eagle-eye vision to micro-drones.

The new camera could be used for medical procedures, such as endoscopies, or to build micro-robots specially designed to measure, explore or survey, the researchers said.

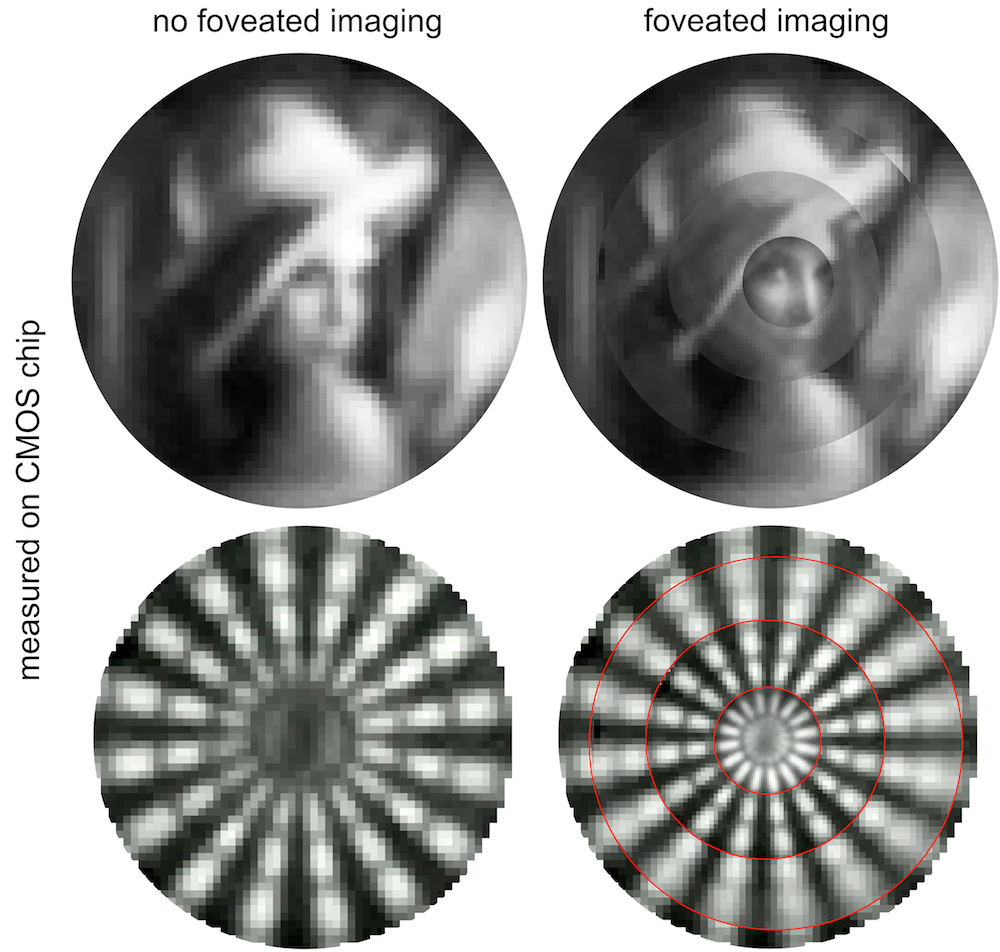

Previously, the engineers used a technique called femtosecond laser writing to 3D-print miniature lenses directly onto an image-sensing chip. To create sharp images like an eagle's eye, the researchers used this process to print clusters of four lenses at a time. The lenses range from wide to narrow and low to high resolution, and images can then be combined into a bull's-eye shape with a sharp image at the center, similar to how eagles see. [Photo Future: 7 High-Tech Ways to Share Images]

"This means that we still cover the whole object and get a better resolution in the center," said study lead author Simon Thiele, a scientist at the Institute of Technical Optics at the University of Stuttgart in Germany. "The drawback is that we lose information in the periphery."

The goal is to optimize the flow of information, Thiele told Live Science in an email.

The four lenses can be scaled down to a footprint as small as 300 micrometers by 300 micrometers (0.012 inches or 0.03 centimeters on each side), similar to a medium-size grain of sand. The researchers said the size of the entire camera setup could decrease with design tweaks to pack in or combine lenses, or as smaller chips become available.

In the animal kingdom, creatures must balance their visual needs and their brain power. The solution in humans and many other vertebrates is known as "foveated" vision, with the sharpest image in the center and a wide range of lower-clarity vision at the edges.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If you had the resolution of the fovea all over your eye, you'd have to carry the visual part of your brain around in a wheelbarrow," said Wilson Geisler, a vision scientist at the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved in the new research.

"If you've got the right application, this could be a very useful technology," Geisler told Live Science. The technology could be used in drones that face challenges similar to animals with foveated vision, with limitations on the bandwidth to send information, but the ability to control movement of the camera to focus on areas of interest, he said.

Thiele said the next step in the research will be to print a lens array on the smallest available image sensors, measuring about 0.04 square inches (1 square millimeter), with the lenses covering more of the surface of the sensor.

Details of the new technology were published online today (Feb. 15) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus