How Dragonfish Open Their Fearsome Mouths So Wide

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

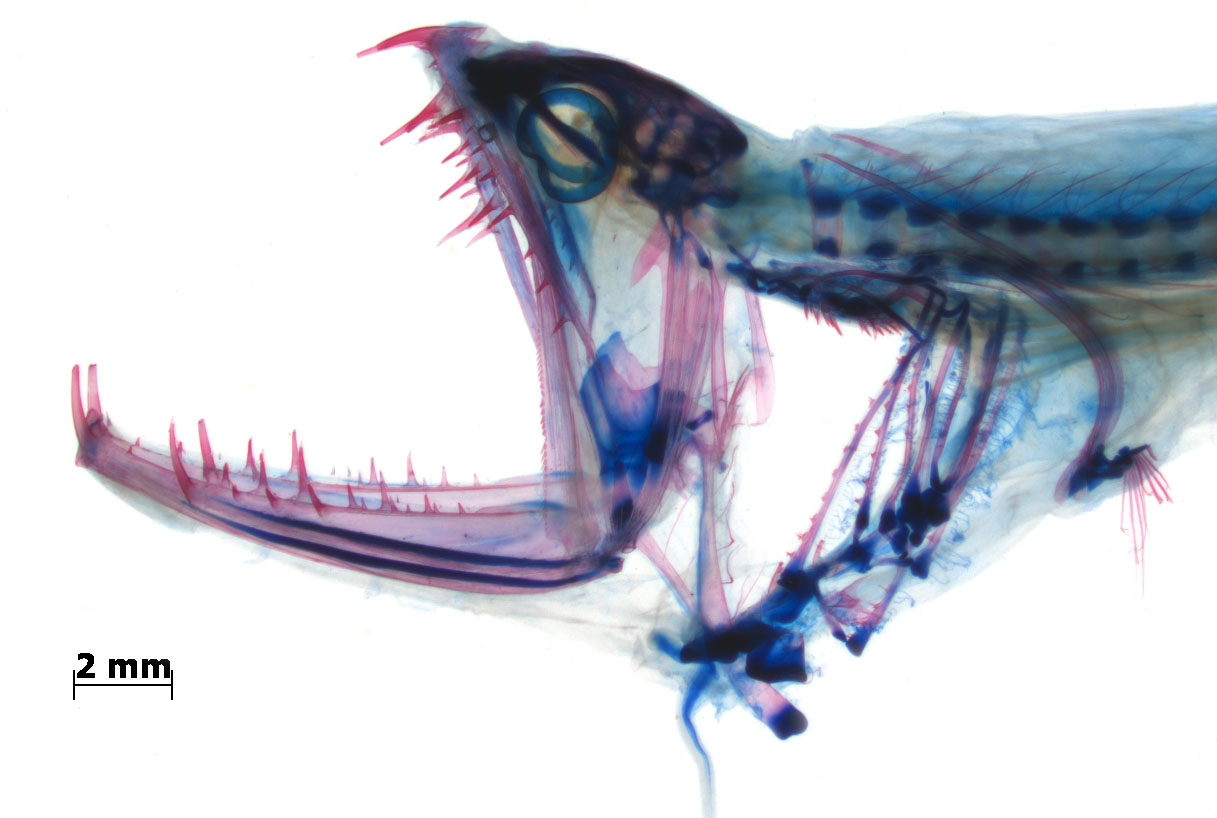

Barbeled dragonfish — predatory fish with long, dark bodies that inhabit the deep sea — are unnerving to look at. Their name refers to glowing barbell-shaped lures that dangle from their oversize lower jaws and attract unsuspecting prey in the cold, dark ocean depths. Those jaws, studded with prominent, sharp teeth, can swing wide enough to gulp down large fish whole — even prey larger than the swallower.

And a new study has discovered one of the secrets to their exceptional gape — a specialized head joint that is unique to dragonfish.

This flexible structure connects the back of the fish's skull to the first vertebra in the backbone, the study authors found. By increasing head maneuverability, this feature could allow a dragonfish to tilt its head farther back as its lower jaw drops, enabling it to open its mouth as wide as 120 degrees. [Open Wide! Scientists Find the Secret to Dragonfishes’ Gaping Jaw | Video]

In most bony fish, the connection between skull and backbone is strongly reinforced through shoulder bones known as the pectoral girdle. For active swimmers, this stabilizes their heads as they move through water, making them more energy-efficient, study co-author Nalani Schnell, a researcher with the department of systematics and evolution at the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris, told Live Science in an email.

Not so in the fish family Stomiidae, which includes barbeled dragonfish. Studies from as early as the 19th century revealed that some Stomiidae genuses (also called genera) lacked a central structure in the vertebrae closest to the head, instead having a flexible rod connecting the head and the vertebral column. A more recent paper described "joint-like articulation" between the head and backbone, Schnell said.

But how that articulation actually operated was far from certain; the only specimens available were fixed in ethanol and rigid, and it was impossible to tell how the joint functioned.

Rubbernecking

Schnell and her co-author G. David Johnson, a marine biologist with the department of vertebrate zoology at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., observed the joint in action by analyzing dragonfish specimens that were cleared and stained — meaning they were soaked in chemicals that render muscle tissue invisible and tint bones red and cartilage blue, but keep the body intact and flexible.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now, the study authors could manipulate dragonfish heads and jaws. They discovered that five genuses of dragonfish had a unique joint, where a supple rod was seated in a type of sheath that wrapped around the back of the skull.

However, when the fish opened its mouth, the sheath stretched to expose the top of the rod, potentially allowing the dragonfish to tip its head back farther and open its mouth even wider — which could provide a significant advantage for deep-sea predation, Schnell told Live Science.

"Food is far more scarce in the dark, deep sea than in the upper layers of the ocean, where photosynthesis occurs," she said. Ambush predators like barbeled dragonfishes save energy by lying in wait for their dinner, rather than chasing it down, so it helps if they're capable of swallowing whatever swims by, no matter how big it is, Schnell said.

The findings were published online today (Feb. 1) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus