An Anglo-Saxon ship buried on the banks of an English river in honor of a seventh-century king carried a rare, tar-like substance from the Middle East on board.

The ship burial and other burial mounds, located at a site called Sutton Hoo, were found nearly 80 years ago along the River Deben in modern-day England. The ship was carrying a type of bitumen, a naturally occurring petroleum-based asphalt, that is found only in the Middle East. [Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep]

"The discovery provides further evidence of prestigious goods travelling over long distances in the early Medieval world before being brought together in this burial," study author Rebecca Stacey, a scientist at the British Museum, wrote in an email to Live Science.

This Middle Eastern petroleum product, however, wasn't Sutton Hoo's only evidence of contact with regions far and wide: An Egyptian bowl, a Middle Eastern textile and silverware from the Eastern Mediterranean were also found on the ship.

However, it's unlikely the Sutton Hoo ship ever raised its sails in the Red Sea. Instead, these precious objects may have changed hands many times before reaching the shores of East Anglia.

"This intercontinental network was mostly likely one of exchange, with items traded or passed as diplomatic gifts between high-status leaders or rulers, maybe passing between several sets of hands before arriving in the East Anglian Kingdom," Stacey said.

Surprising find

Sutton Hoo, which was first unearthed in 1939, was one of the most magnificent burial settings ever uncovered in Britain. The 90-foot long (27.3-meters) ship was part of a huge complex of 18 separate burial mounds near modern-day Suffolk, and the ship itself was laden with opulent treasures, including gold and garnet jewelry, silverware, coins and armor. Many scholars believe the ship was buried to honor King Raedwald of East Anglia, who died in A.D. 624 or 625, according to the study researchers. If the king's body was buried on the ship, archaeologists think it must've been completely eaten away by the acidic soil over the centuries, the researchers wrote in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

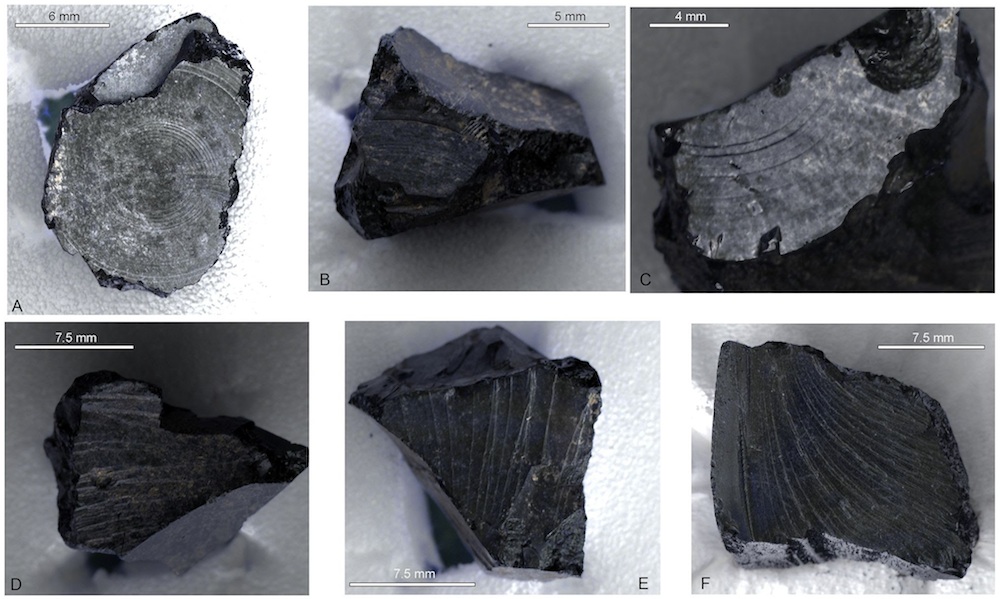

Throughout the ship, archaeologists found bits of black carbonaceous material, long thought to be Stockholm Tar, a substance used to waterproof ships. The boat itself showed evidence of wear and tear and had likely navigated narrow rivers and shallow coastlines. For the burial, people likely dragged the Sutton Hoo hundreds of feet inland from the Deben, the researchers reported today (Nov. 30) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Stacey and colleagues stumbled upon the new find while researching tars in many different ancient European shipwrecks. They referred back to the original chemical analysis of the tar from the 1960s, and they realized analytic techniques had improved dramatically since then.

So the team members did their own investigation using an array of newer tools and techniques, including separating the material into layers, using reflecting light waves to identify its chemical makeup, and measuring the fraction of carbon isotopes, or versions of carbon with different numbers of neutrons, in the material.

The team was in for a surprise: The tar-like substance on the Anglo-Saxon ship was actually bitumen with origins in the Middle East. Though it's not clear exactly what it was used for, the bitumen may have originally been attached to some other object, such as leather or wood, that has since worn away, the authors wrote in the paper.

"There are intriguing faint concentric lines on the surface of some of the bitumen pieces that might indicate where something turned was adhered, or possibly that the bitumen itself was turned to shape it into an object," Stacey said.

However, bitumen was also prized as a medicinal tonic, so even lumps of rough bitumen may have been seen as valuable, Stacey added.

Though Vikings are perhaps the most famous people to have buried their high-status society members in ships, ship burials were common throughout Northern Europe for many centuries. Memorials also indirectly honored the seafaring culture. For instance, as far back as 3,000 years ago, people in the Baltics built stone ships to honor their ocean-voyaging lifestyle.

Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus