HIV's 'Patient Zero' Wrongly Blamed for AIDS Epidemic

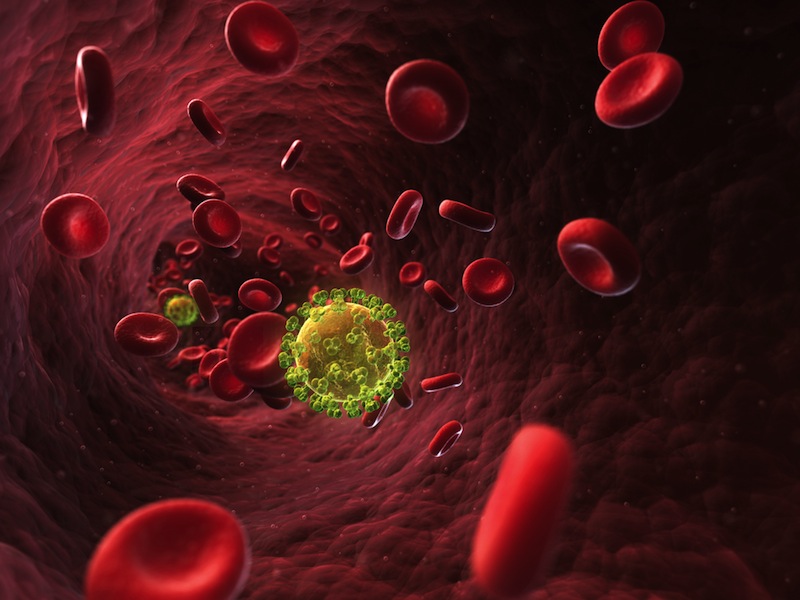

A man who was believed to have introduced HIV to North America — the man sometimes referred to as "Patient Zero" — was actually not the initial source of the virus on this continent, new research shows.

Rather, this man was one of the thousands of people in North America who were infected with HIV in the years before the virus was officially recognized, according to the new findings published today (Oct. 26) in the journal Nature.

The man, Gaétan Dugas, was a Canadian flight attendant, and was thought to have introduced HIV into one or more major U.S. cities by infecting his sexual partners, setting off the AIDS crisis that struck the U.S. in the 1980s, the researchers said. Dugas died from AIDS in 1984.

"Gaétan Dugas is one of the most demonized patients in history, and one of a long line of individuals and groups vilified in the belief that they somehow fuelled epidemics with malicious intent," study co-author Richard McKay, a historian at the University of Cambridge in England, said in a statement. [Top 10 Stigmatized Health Disorders]

The first AIDS patients were recognized in San Francisco and other places in California, in 1981. But the new results show that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes AIDS, likely first arrived in the U.S. in New York City in 1970, the researchers said.

HIV in North America

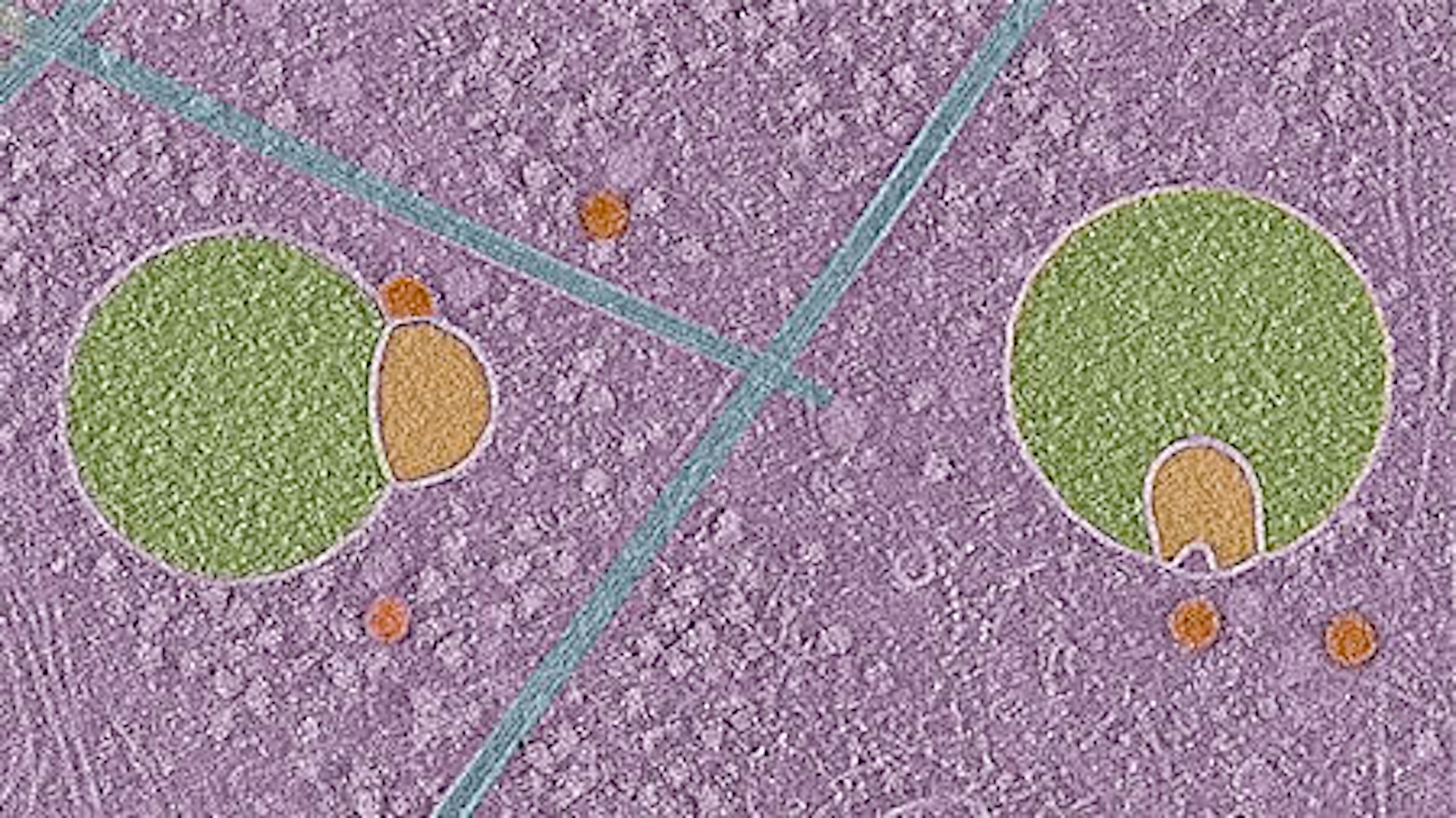

In the study, the researchers looked at historical and genetic evidence to figure out exactly how and when the HIV virus emerged in North America. They conducted genetic testing of blood samples collected during 1978 and 1979 from men living in New York and San Francisco who were later found to be infected with HIV.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers used a new technique, called "RNA jackhammering," which allowed them to break down the genetic material of the virus within the blood samples into smaller chunks, and extract one of the most crucial components of the virus, called RNA. They used the information they found to construct an evolutionary "family tree" of the virus.

The findings showed that the HIV circulating in the U.S. was already surprisingly genetically diverse in the late 1970s, the researchers said.

The findings also showed that it was the arrival of HIV in New York that sparked the North American HIV epidemic, the researchers said. The city wasthe crucial hub from which the virus spread across the continent, including to San Francisco, they said. [The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

"Our analysis shows that the outbreaks in California that first caused people to ring the alarm bells and led to the discovery of AIDS were really just offshoots of the earlier outbreak that we see in New York City," study co-author Michael Worobey, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, said in a statement.

Moreover, the researchers looked at genetic material from Dugas and found that he was not the source of the virus's epidemic in the U.S. "This individual was simply one of thousands infected before HIV/AIDS was recognized," McKay said during a news briefing on the findings.

Dugas was once designated as Patient "O" (as in the letter "O") by investigators in the 1980s who conducted an early study on AIDS cases in California. The designation was used because Dugas was from "Out(side)-of-California." However, that "O" nickname was later misinterpreted as a "0" (as in the number zero) and contributed to the labeling of the man as "Patient 0," which people thought meant that he was the first case in the outbreak, the researchers found.

The new results show that, when it comes to the start of the HIV epidemic in North America, "it was not a single bad actor," said Dr. Bruce Hirsch, an attending physician of infectious diseases at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the study.

Overall, the origins of epidemics can usually be traced back to communities of vulnerable individuals, but not to a single person, he told Live Science. "I think that is an important way of understanding HIV and other epidemics," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.