Promising Ebola Drug ZMapp: The Real Lessons of an Inconclusive Study

In the midst of the 2014 Ebola outbreak, a drug called ZMapp was one of the most promising treatments for the disease. But now researchers have published a study of the medication in people, and the results are somewhat anticlimactic.

Rather than providing an answer to whether ZMapp can really cut the risk of death from Ebola, the results are inconclusive.

The researchers did find that a smaller percentage of people who were treated with ZMapp died from Ebola, compared with people who didn't receive the drug. But this finding did not meet the researchers' criteria for a meaningful difference between the groups. That means the difference could have been due chance; in scientific terms, the finding was not "statistically significant."

Ironically, the success of other measures to fight Ebola during the outbreak appear to have affected the ability of the ZMapp trial to draw a precise conclusion. By the time the trial started, in March 2015, the outbreak was drawing to a close, and few people were being newly diagnosed with Ebola. The researchers had planned to enroll 200 people in their study of ZMapp, but were able to enroll only 72 people before the study was cut short due to a lack of new Ebola cases.[10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

"The laudable and rapid decline in eligible new cases of [Ebola virus disease] was a factor that no trial design could anticipate, and it affected our ability to reach definitive conclusions," the researchers wrote in the Oct. 13 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Despite the efforts of many researchers in this and other trials, "the outbreak appears to have ended with no incontrovertible evidence" that any proposed treatment for Ebola is better than the supportive care typically given to patients, the researchers said. Such supportive care included, for example, giving fluids to prevent dehydration and maintain adequate blood pressure.

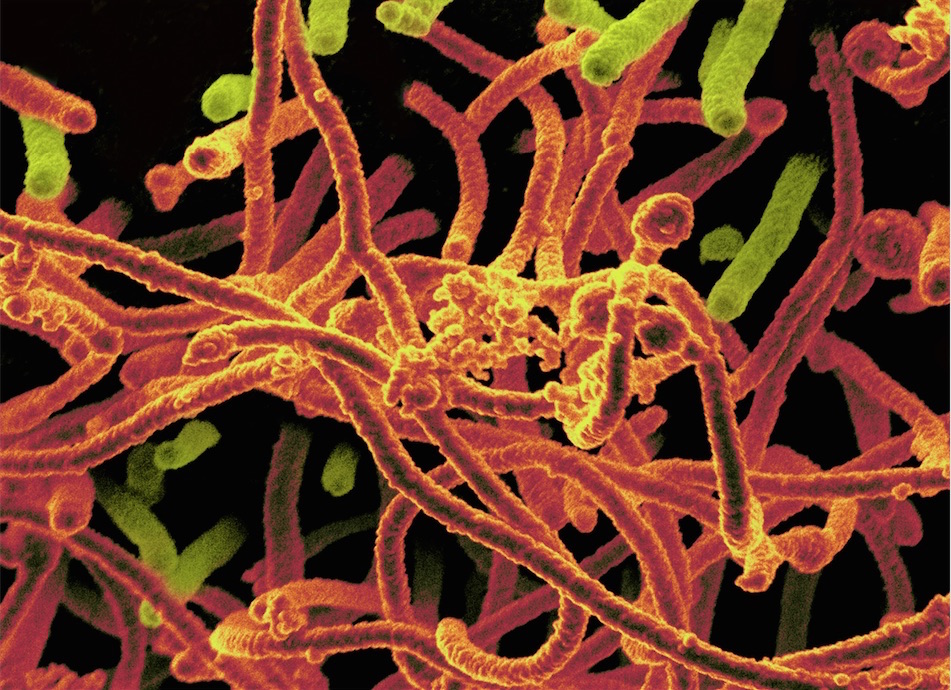

ZMapp entered the spotlight in August 2014, when the drug was given to an American physician, Dr. Kent Brantly, who had contracted Ebola while working in Liberia. Brantly survived the disease, but there was no way of knowing whether ZMapp helped him. The drug contains three antibodies that are designed to attack the Ebola virus.

In the new study, people with Ebola in West Africa were randomly assigned to receive either the drug or the standard supportive care for Ebola patients.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

About 30 percent of all patients enrolled in the study died from Ebola. The death rate among patients who received ZMapp was 22 percent (eight out of 36 people), while the rate among those who didn't receive the drug was 37 percent (13 out of 35 patients). Still, because of the small number of patients, the researchers' statistical analysis showed that it wasn't clear whether the difference between the groups was due to the drug or to chance.

The researchers also noted that many of the patients who received ZMapp likely didn't get the drug until at least a week after they had been infected with the virus. Previous studies in animals had suggested that the drug is most effective when it's given within five days of infection.

Despite the inconclusive results, experts said there were several positive points to be made about the research.

The study showed it is possible to do high-quality studies during a public health emergency like an Ebola outbreak, said Dr. Jesse Goodman, director of the Center on Medical Product Access, Safety and Stewardship at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the study. That's "an important contribution" to the field of public health, Goodman said.

What's more, although researchers can't draw definitive conclusions from the study, "it's pretty strong supportive evidence that this drug probably has some efficacy in [treating] Ebola," Goodman said.

The study also provides a lesson about doing research during an outbreak, he said. Part of the reason the study did not start sooner was because some people were resistant to the idea of doing a trial where not all participants would get an experimental drug that looks promising, Goodman said. But in the end, such studies, known as controlled trials, are needed to show whether a drug really does work to treat a disease, he said.

"What people think works based on [studies in] a test tube or animal often doesn't work in humans," Goodman said. "People saying it's unethical to do a controlled trial during a serious outbreak really did not serve us well in this case."

Researchers should now think about the types of studies that could be done in future outbreaks, such as studies of vaccines and other experimental Ebola treatments, and figure out how those studies could be designed, Goodman said. Resolving these issues before there is an actual outbreak would help researchers start the studies sooner, he said.

The maker of ZMmapp, Mapp Biopharmaceutical, Inc., plans to continue with the development of the drug as a treatment for Ebola, according to a statement the company released earlier this year.

The study was funded in part by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.