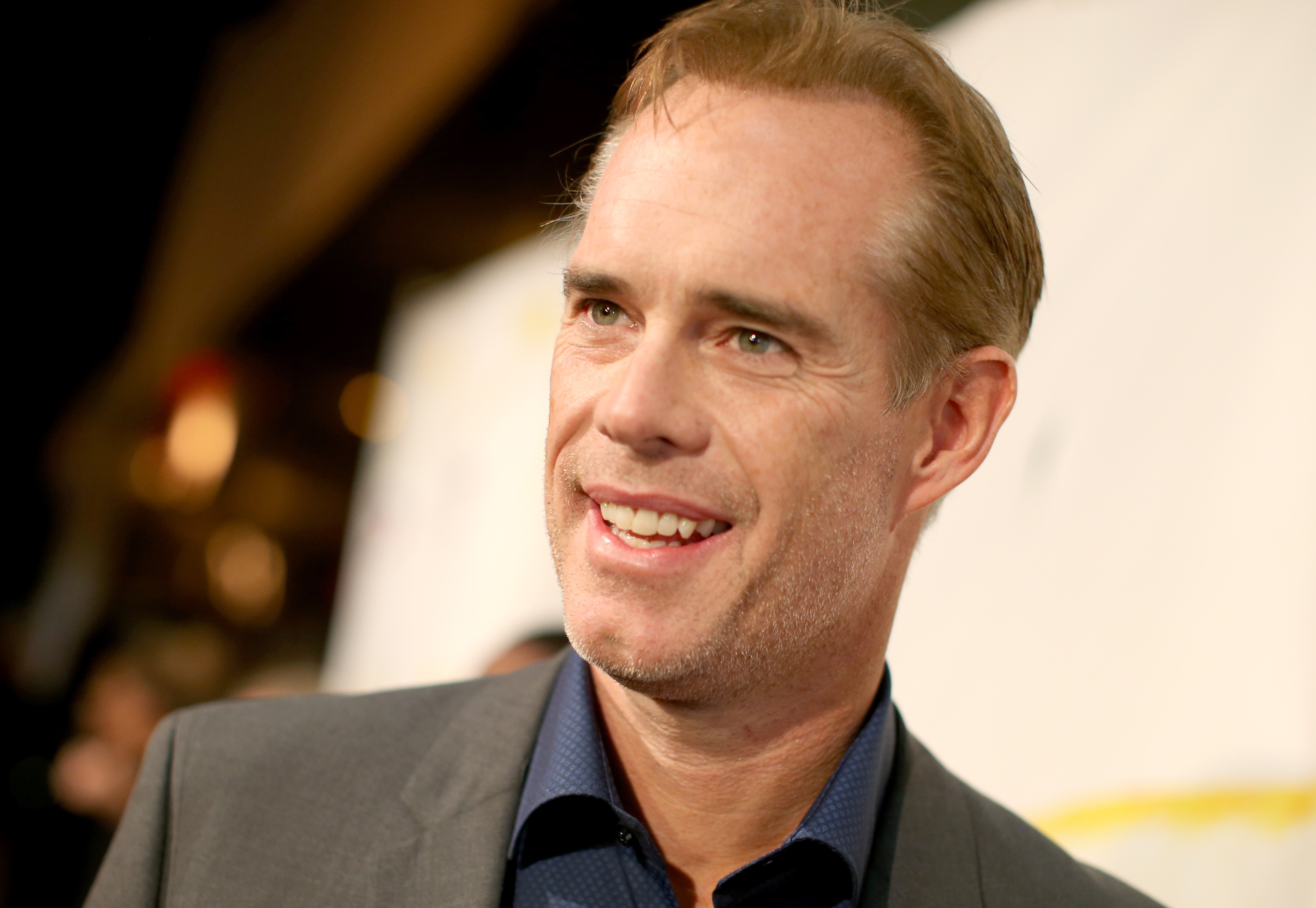

Hair Plugs? Joe Buck Puts Cosmetic Addictions in Spotlight

Fox Sports announcer Joe Buck recently shared that he had an addiction to hair plugs, and it almost cost him his career.

In an exclusive with Sports Illustrated and in his upcoming memoir, Buck described the overwhelming fear he had of losing his hair. The possibility of balding so consumed him that in 1993, at age 24, he had his first hair-replacement treatment. He wrote in the book that, after the procedure, "I, Joseph Francis Buck, became a hair-plug addict."

Hair-replacement treatment and other cosmetic or appearance-altering procedures may seem commonplace in modern entertainment, and experts have said the treatments indeed can become debilitating addictions. But how do these addictions begin, and what can be done to treat them? [Top 10 Stigmatized Health Disorders]

It's possible that a tremendous fear of hair loss and an addiction to hair plugs could be linked to both a self-esteem issue and external social influences, said sociologist Amnon Jacob Suissa, a professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal who has studied different forms of addiction, including cosmetic surgery. Suissa has not treated Buck.

This type of addiction is linked to an intimate self-perception, or what the person thinks when looking at himself or herself, Suissa said. But it can also be influenced by media, and for Buck, being in the public eye could have exacerbated his already skewed self-image.

"There are definitely social norms, especially in the Western world, where there is a supremacy of the image, where the body has to be perfect," Suissa told Live Science. These social norms may be linked to the rise in cases of certain psychological disorders, such as anorexia and bulimia, he said. "In media and entertainment, the image is more important and is a mark of hierarchy in the group. By extension, it becomes the goal, consciously or unconsciously, to take care of your body to survive."

People with an addiction related to their self-image, whether it be an addiction to hair plugs or cosmetic surgery, generally go through four phases, Suissa said. Phase 1 is the negative feeling about the individual's appearance and not being able to manage it, which leads to phase two: trying to fix the problem with a medical procedure. Then after that procedure, in phase three, the person develops a feeling of control over the low self-esteem and the negative emotions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In phase three, they feel temporarily better, but it is all artificial," Suissa said. "Because in phase four, they wake up in the morning and they look once again in the mirror, and they think, 'What happened to me?'"

It's in Phase 4 that the addict will seek help, because his or her distress is so high, Suissa said.

To treat addiction to something like cosmetic surgery, it is important to focus on the deeper issue, Suissa said. For example, in Buck's case, the problem was not actually his hair, but rather the relationship he had with his image, Suissa said.

Addiction counselors, doctors and other treatment providers focus their efforts on identifying the root issue and healing from there, Suissa said. This kind of approach could lead to the diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder or a similar mental disorder, he said.

For Buck, it was the loss of his voice after something went wrong during a hair treatment procedure in 2011, that led him on the road to recovery.

"I had this situation with my voice that rocked me to my knees and shook every part of my world," Buck told Sports Illustrated. "I'm 47 years old now and willing to be vulnerable sharing a story."

Buck shared more about this point in his life in a new memoir, "Lucky Bastard: My Life, My Dad and the Things I'm Not Allowed to Say on TV," (Dutton), to be released on Nov. 15.

For most people with this type of addiction, "you need to take the time re-underlining the sources of pleasure you had before you went into this cycle of addiction," Suissa said. "And make sure that what's important — such as loved ones — is what counts the most for you."

Original article on Live Science.