Doomed 16th-Century Warship Yields Secrets with New 3D Models

In 1545, when the English warship Mary Rose capsized as it led an attack on a French invasion fleet, it sank so quickly that most of the 400 crew and soldiers on board drowned. But now the story of one of the crewmembers lost on the Mary Rose is being told through an online set of high-definition 3D models, featuring some of the tools and personal belongings of the ship's carpenter — as well as his skull.

Researchers are studying the many human remains recovered from the famous wreck of the Mary Rose since it was rediscovered in 1971 and raised to the surface in 1982. In particular, the new project is shedding light on the experiences of a carpenter who sailed aboard the doomed warship.

"Obviously, the carpenter on a wooden warship is a very important person," said Nick Owen, a biomechanist at Swansea University in the United Kingdom and one of the leaders of the study. "So this is a tale of an important member of the crew, a real person who had a real job, who under different circumstances would have been lost to history, forever." [Sunken Treasures: The Curious Science of 7 Famous Shipwrecks]

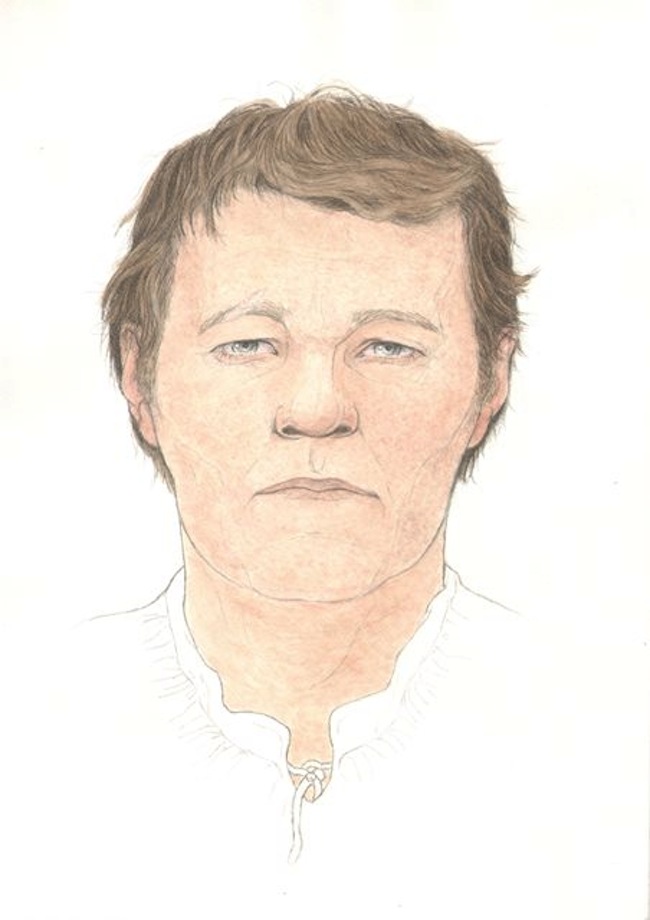

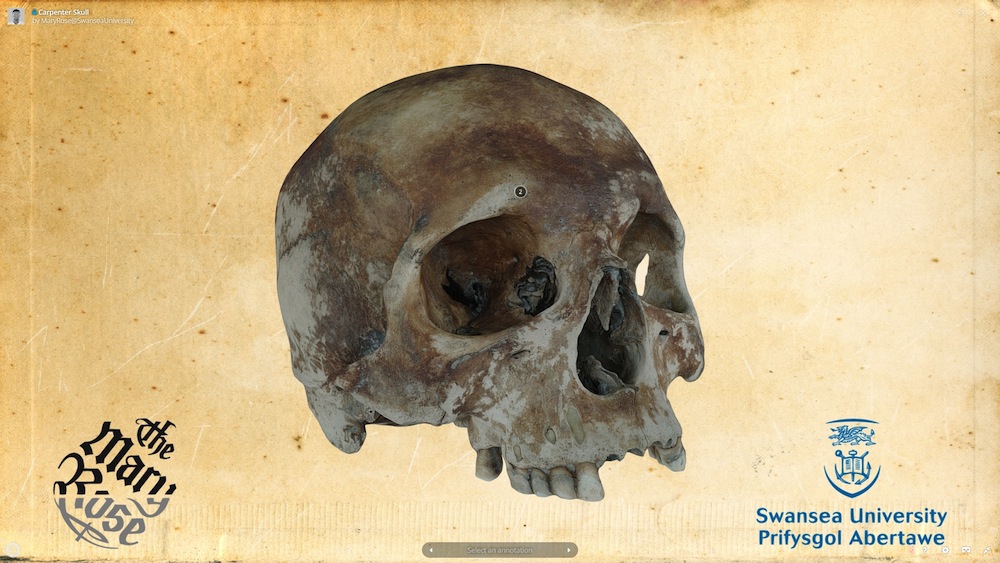

Owen's research includes using techniques from sports science to study the remains of the Mary Rose crew. The 3D models published on the research team's new website, VirtualTudors.org, were created by team member Sarah Aldridge of Swansea University, who used high-definition photogrammetry to scan an assemblage found below decks in the warship wreck that archaeologists have identified as the remains of the ship's carpenter, with his tools and personal belongings.

As well as the carpenter's skull, the models include the wooden remains of several woodworking tools — the metal pieces have long-since corroded away — and carved wooden items such as a spoon and an ornamental panel. There is also a leather shoe that was found with the remains, in surprisingly good shape after its centuries under the sea, the researchers said.

All the models have been made available to the public on Sketchfab, which means they can be embedded on other websites.

Digitizing archaeology

The 3D models relating to the carpenter on the Mary Rose are the public-facing side of a research project that aims to learn how effective digital models can be for scientists studying archaeological remains and artifacts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists who register on the website to take part in the study will see an additional collection of 3D models: the skulls of 10 people that have been recovered from the wreck of the Mary Rose. [Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep]

These skull models were created using the same photogrammetric process as the 10 models about the ship's carpenter, and they will be used to study how digitized remains are used by remote researchers.

"There's this view that you need to study the real remains — that you can have digital versions, but you can't really do analysis," study co-leader Richard Johnston, a materials specialist at Swansea University, told Live Science.

As such, the models will help researchers identify the strengths and weaknesses of using digitized remains for analysis, he said.

Johnston explained that accurate digital models of archaeological remains and artifacts can both better protect the original items from damage caused by even gentle handling, and can provide greater access to unique remains and artifacts throughout the scientific community.

"So you broaden the number of people looking at them, and you also increase the diversity of the researchers who have access to the remains," Johnston said.

Of shoes and ships

Beyond the value of digitized remains for scientific researchers, these virtual models also have a clear appeal to members of the public who are interested in the story of the Mary Rose, Owen said.

"In a way, you get [closer] to these things in 3D than you would in the museum itself, because they would all be behind glass," he said.

For both leaders of the research project, one item in particular stands out for its personal connection to the ship's carpenter — his shoe.

"The skulls fascinate because they are people — and when osteologists look at those they can tell things about that person as an individual. So that is pure history, brought to life by osteologists," Owen said. "However, having said that, I think the shoe is fantastic. If you had to buy a pair of shoes like that today, they wouldn't be cheap. You can see the stitching on it, and somebody stitched that by hand — it sort of transports you back to Tudor England."

Johnston added that the shoe isn't altogether different from current styles worn today. "And the leather is so intact, with a bit of glue you could almost wear that again — which is remarkable considering it is 500 years old, and that it was buried under the sea," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.